What is a university? English poet John Masefield said it “is a place where those who hate ignorance may strive to know.” Dartmouth says it is a “voice crying out into the wilderness.” But, in an age where universities have budgets larger than the GDPs — gross domestic product — of many small nations, I take a more practical approach: A university is what it spends money on.

In recent years, however, Dartmouth’s budget is moving further from our values: spending more money than ever on bureaucratic non-academic staff, while hiking up prices for students. Past budgets show that this spending is not necessary. If we truly want to serve our students, our academic staff and our ongoing pursuit of knowledge, this needs to change.

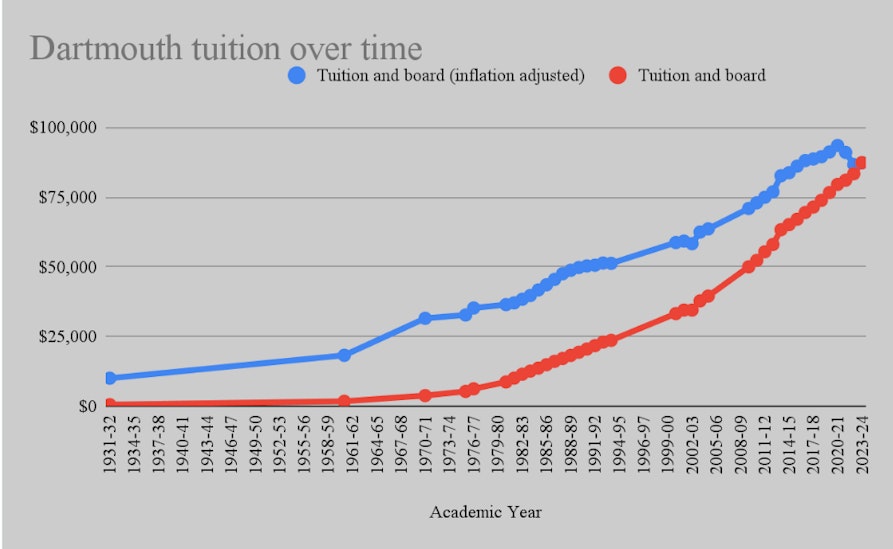

Over the past 35 years, Dartmouth’s yearly tuition has shot up from $18,199 to $87,315. Even accounting for inflation, that is more than double. Donations have also increased. This money is not being funneled into savings, but rather, it is used to fund the swelling cost of running this school. In the past 50 years, the total expenses of the College have increased by over three times, despite the number of students not even doubling.

But why? Why has the cost of a Dartmouth education exploded in the past few decades? What is the College spending its money on?

To answer this question, we need to look back into Dartmouth’s history.

Every year Dartmouth publishes a financial statement, endowment report and an audit report. However, despite the numerous pages of numbers and calculations listed in these reports, answering the question of where exactly the money is going is surprisingly hard.

The report shows $600 million, around half of the budget, being used on “Academic and Student Programs.” However, this category includes much more than instruction and research, such as: admissions advertising, admissions coordination, libraries, various centers and institutes including the Hopkins Center for the Arts and the Hood Museum of Art, athletics, club funding through the Committee on Student Organizations and some technology services costs.

Dartmouth does not publish what is spent specifically on instruction costs and research. While older Dartmouth budgets list the amount spent on “instruction” and “instruction and departmental research,” the current budgets do not list that category. Nonetheless, by looking at the number of professors and teaching faculty, we can estimate that the total amount spent on instruction and research is significantly less than the amount spent on “Academic and Student Programs.”

In fact, we find that while Dartmouth’s spending has exploded, the estimated amount spent on academic staff has only modestly increased. As seen in the graph below, while around one-third of the budget was spent on instruction in the 1960s and 1970s, now it is only one-tenth. In the meantime, the faculty to student ratio has stayed relatively constant, despite the soaring costs for students.

There is one place where this increased tuition decidedly has not gone: professors, research and teaching staff.

However, there are other areas where students and faculty have complained about numerous budget-cutting decisions in the past few years. In 2015, professors publicly campaigned for salaries to be on-par with other Ivy League schools. Many amenities, such as housing facilities, have been in need of renovations for years. You need only to walk past the Choates resident hall cluster to see this firsthand. Recently, library staff have been cut in an effort by the College to cut down on expenses, and the College permanently shut two out of its five libraries. Meanwhile, Dartmouth Dining and other service jobs are in a perpetual labor shortage. Dartmouth Dining was even threatened with a strike by student workers last winter, perhaps due to uncompetitive wages for many local workers.

But in a world where tuition and overall budget have more than doubled since the 1950s, how are we still facing these basic issues? And why have basic functions of the school — like the number of faculty or their salaries — not similarly increased?

The answer to this is uncomfortable: Dartmouth’s price hikes have been largely going to fund a growing, non-academic, bureaucratic staff.

Dartmouth says that its total payroll is $418.5 million, excluding the salaries that are funded by the endowment or the fringe pool — expenses related to an employee’s salary or wage. That’s around half of the $958 million in annual expenses. I estimate that the amount spent on academic staff is only around one-fourth of the total payroll spending. That means that Dartmouth is spending a massive chunk of its budget on non-academic staff specifically. And when considering the added costs of administrative buildings and resources, this cost grows even more.

According to publicly available tax returns from 2022, the highest-paid employee at Dartmouth is not a professor or even the President; it is Alice Ruth — the Chief Executive Officer of the Investment Office, who made over $4.2 million last year. That is the budget of an entire small academic department. The next highest earners — whose compensations are legally required to be disclosed on Dartmouth’s yearly tax audits — received salaries between $1.8 and $1.1 million. None of these individuals are professors, department heads or research scientists. Nor are they related in any capacity to teaching or research. These people are members of a non-profit university administration who are making more than the CEOs of many tech companies.

Universities do need a bureaucratic system to handle tasks like organizing meetings and payments, managing paperwork and setting up events. These are undoubtedly important tasks, and many people in these roles work hard to make sure that students have the best experience at Dartmouth possible. But how is it that even as advancing technology should make all these tasks easier, the percentage of the budget going to non-academic staff has drastically increased? It seems that this extra spending is not necessary, but rather the result of a decades-long bureaucratic creep which we have all become complacent with.

Looking into the budgets of Dartmouth’s past, one can see that the current system is not immutable. It is possible to run a university with significantly less bureaucracy. It is possible to go back to spending one-third of the budget on professors, rather than one-tenth. Dartmouth’s budget has changed significantly over the past 50 years, and it has the potential to change again. Dartmouth has the potential to decrease tuition, while still improving the quality of its education, libraries and dorms.

Dartmouth’s mission statement is “[to] educate the most promising students and prepare them for a lifetime of learning and of responsible leadership through a faculty dedicated to teaching and the creation of knowledge.” Dartmouth’s admissions website advertises research and degree programs. These are the reasons why students choose to attend this college and why alumni donate. This is what makes Dartmouth renowned.

As the university moves into a new chapter with the entry of President Sian Leah Beilock, I hope that we can see these concerning trends reverse. I hope that Dartmouth is able to learn from its past and let its budget reflect its values of education, research and knowledge. But, in order to do that, we must first recognize that something has gone profoundly wrong.

Opinion articles represent the views of their author(s), which are not necessarily those of The Dartmouth.