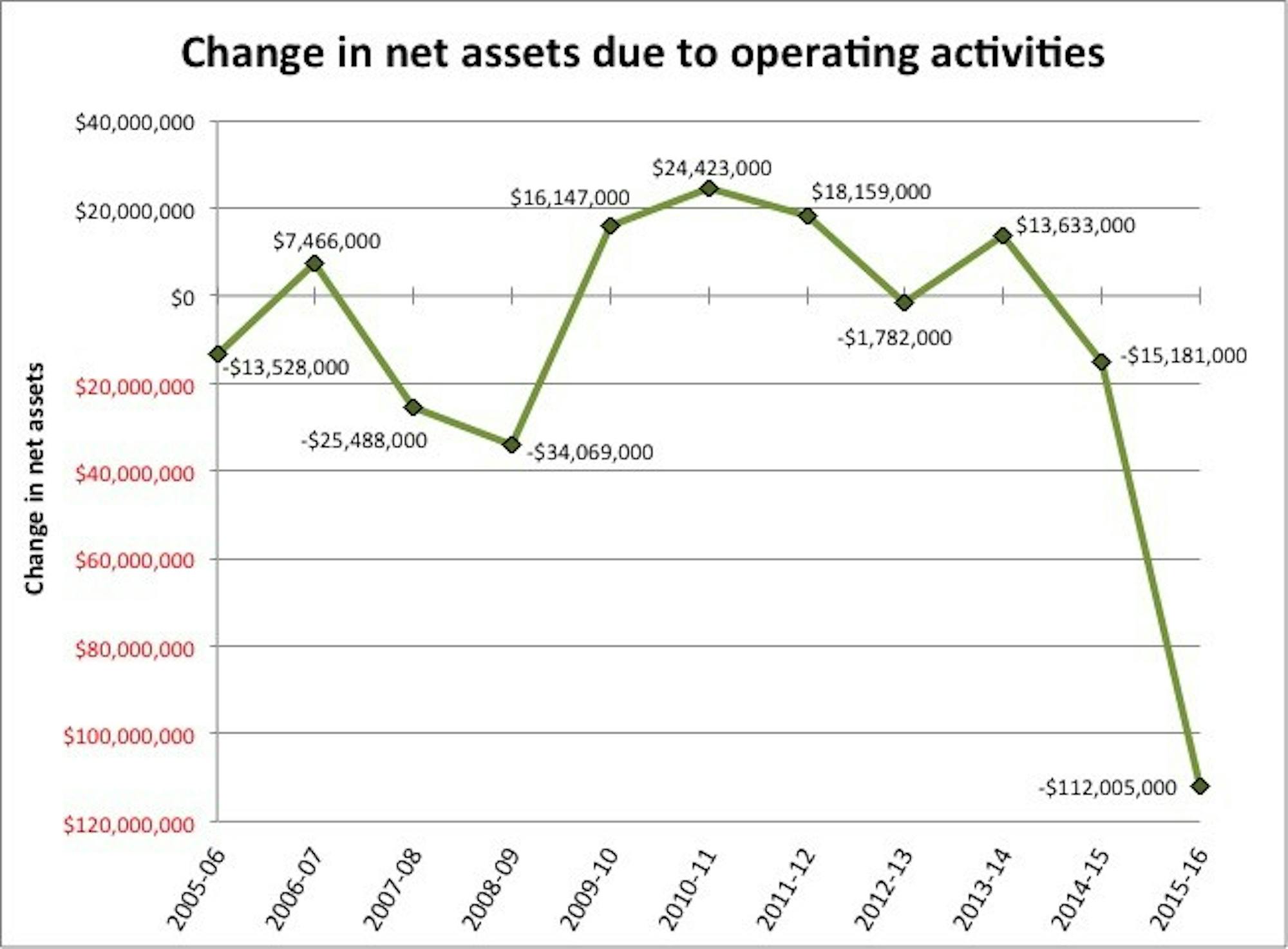

Due to a combination of rising expenses and flat growth in revenues, in conjunction with the reorganization of the Geisel School of Medicine, the College suffered a financial operating loss of $112 million this last fiscal year, compared to a $15.2 million loss reported the prior year.

In addition, the College’s endowment declined by $189.1 million, from roughly $4.7 billion to $4.5 billion.

In an interview, chief financial officer of the College Mike Wagner cited sluggish investments and increasing expenses and decreasing tuition revenues as a few of the reasons for the operating losses.

The reorganization of Geisel listed an accounting charge of around $53.5 million, all of which was counted under the College’s expenses for the 2016 fiscal year, even though they will be paid in future years, Wagner said. The expenses consisted of severance agreements for faculty and staff, facility costs and associated costs of moving certain operations from Geisel to Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, he said.

Revenue stagnation has also complicated the matter and led to increasing losses for the College. Revenues dropped two percent, from $876.2 million to $859.6 million, while expenses grew three percent, from $891.4 million to $918.1 million.

Many of the expenses listed in the operating losses are very large because they are currently unfunded, since the College plans to fund them through future revenues, Wagner said.

Depreciation of financial assets, or the devaluation of them over time, has also taken a toll on the College, as it has been using cash to pay expenses such as building repairs and health benefits for retirees, Wagner said.

The depreciation of the College’s financial assets over time has reduced the value of future budgets, since funds are decreasing and current expenses are planned to be paid through future revenues.

As a part of the same interview, executive vice president Rick Mills said that the College has an obligation to provide health benefits for its retirees.

“We can change that obligation theoretically, but so long as we have that obligation there is this future expense that we have to sustain,” Mills said. “But there is this accruing accounting burden of obligation that we are required to recognize and shows up as a deficit, but it doesn’t show as cash that we don’t have this year.”

Investment income was also a reason for the losses, as the returns in cash and working capital were less in the 2016 fiscal year than they were in the 2015 fiscal year, although this trend was not limited to Dartmouth, Wagner said.

In the 2015 fiscal year, the College had a special distribution from its endowment of about $17 million that did not recur in the 2016 fiscal year. Additionally, research revenues and unrestricted gifts for current College operations remained flat in 2016 compared to 2015, Wagner noted.

The College raised $250 million in April by issuing Series2016A bonds, which brought the College’s long-term debt down to $1.2 billion.

In particular, the College saw minimal revenue growth in net tuition, which is the net revenue the College receives after financial aid is deducted from billed tuition. Though net tuition accounts for roughly a quarter of the College’s funding, it saw growth of less than one percent, Wagner said.

“I think with tuition levels where they are there aren’t ways for net tuition to grow,” Mills said. “If you want to reach the best students and offer financial aid and want to put a lid on just growth and tuition charge, you are inherently continuing to squeeze that revenue source. I think that is true for everyone.”

The slow growth can be accounted for in part by the College’s philosophy of need-blind admissions for all domestic applicants and commitment to meeting fully demonstrated financial need for admitted students, Wagner said.

The losses are not unique to Dartmouth, as many other university endowments have faced challenges in the stock market, Mills said. He also said that federal funding, a traditional source for growth, is not expected to improve in the future, which also contributes to the difficulties higher education faces.

Among the other Ivy League colleges, Brown University, Cornell University, Colombia University, Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania saw negative returns on investment for their endowments over the past fiscal year. Princeton University and Yale University saw positive returns.

In the past, research funding typically went to specific fields of science, such as cell biology or immunology, Mills said. However, there has been a shift toward allocating money to solve real-world problems, which often requires interdisciplinary research. He said that the College should focus more on collaboration between fields in order to secure grants for research.

The College currently has an academic cluster initiative spearheaded by College President Phil Hanlon that emphasizes cross-disciplinary work.

In the future, the College plans to focus on making sure expenditures go to areas that need funding the most and ensuring that any new activities that require funding do not significantly impact the budget, Wagner said.

The College is expecting to continue to run operating deficits in future years, even though the operational budgets for the 2018 fiscal year and onward are still being developed, he said.

The size of operating deficits in the future will also depend on whether healthcare interest rates go up, which would reduce the cost for the College of insuring post-retiree health, and upon potential changes in life expectancies, Mills said.

In regards to market fluctuations, Mills said that Dartmouth was in a relatively good spot.

“We are a wealthy enough institution with a well-established brand and a clear quality level that there are going to be people below us ... that there are places that are less affluent than us in terms of brand or academic quality that are going to be affected first,” Mills said. “I think we have a bit of a cushion and the luxury to be able to sort out what we are doing and realign things, whereas other institutions may have less time.”

However, the College tracks many indices of costs and is worried about inflation and increases in recruitment and retention of employees, both of which can put upward pressure on expenses, Wagner said.

Mills said that he expects the College, as well as other members of the Ivy League, to spend the next five to ten years figuring out how to adjust to shifts in the financial climate. Questions about the role of technology and how much time higher education institutions have to adjust will also affect their thinking, he said.

Financially, things are not expected to return to how they were in the past, Mills added.

“I don’t think [the College’s financial situation] will go back to where it was — it is more like a warning light going on in your car,” he said. “It is not like you have to pull over right now. It is not your oil pan is ripped open, and your engine is going to seize, but you got a warning light. You should finish your trip and call a mechanic and talk about what you are going to do.”