Two games remain in the Dartmouth men’s basketball team’s schedule, but its in-conference fate has long been decided. Stumbling to a 1-6 Ivy League mark start and mathematically eliminated from contention three weeks before the season’s end, the Big Green, now 3-9 in the conference, appear destined to finish somewhere in the fifth to eighth range in the standings. As it closes out a testing year, it’s worth assessing where things went right and wrong — especially for a team that has not experienced a conference win percentage decline from the prior season since 2009-10.

The defining trait this season, especially more pronounced in conference play, is that the Big Green’s control and efficiency during games has not been proportional to its winning percentage. A look at possession time with the lead best encapsulates this — during Ivy games, Dartmouth has led 47.6 percent of total game time and its opponents 45.1, yet that has produced a mere 3-9 record. In five games this season decided by five points or less, Dartmouth lost all of them, including two that went into overtime.

“We weren’t able to complete plays, make big shots, just making winning plays down the stretch when the opposing team turned up the screws,” head coach Paul Cormier said.

Cormier also referred to a lack of experience and point guard stability.

“We didn’t have the experience to combat [an opposing surge],” Cormier said. “I would say it’s 50-50. You have to have a true point guard who understands, what we call, time, place, situation, and we didn’t have that.”

Much of this resulted from difficulties towards the end of games, but at some point it goes beyond closeout failures. In that vein of thought, very convincing evidence exists that some of these late-game travails can be ascribed to poor luck. According to KenPom.com, out of 351 Division I college basketball teams, Dartmouth has the second worst luck rating — a measure of the deviation between a team’s per game efficiencies and winning percentages — in the entire country.

Several indicators bear this understated efficiency out. While the Big Green is currently tied for the second-worst winning percentage in the league, it has accrued the fourth-best scoring margin. Moreover, per Sports-Reference, two advanced stats — net rating, which estimates point differential per 100 possessions, and simple rating system, which considers point differential and strength of schedule — places the team above where simply wins and losses do.

In sum, it’s unprecedented and abnormal how little Dartmouth’s efficiency and control of games has translated into victories. If the season was longer, for example, the team’s actual quality would have been better reflected in a larger sample of games — and thus more victories.

At the same time, in an area more within its control, Dartmouth’s shot distribution continues to lag. In the last decade or so, but especially as of late, the NBA and the sport more broadly has increasingly prized 3-point shooting for its scoring efficiency and other benefits such as spacing the floor. The best shot will always be the open one, but aside from that, the most efficient ways of scoring are with the 3-point shot, followed by drives to the rim (high-percentage looks closer to the basket) and free throw generation. That leaves the midrange shot as the least efficient in the sport.

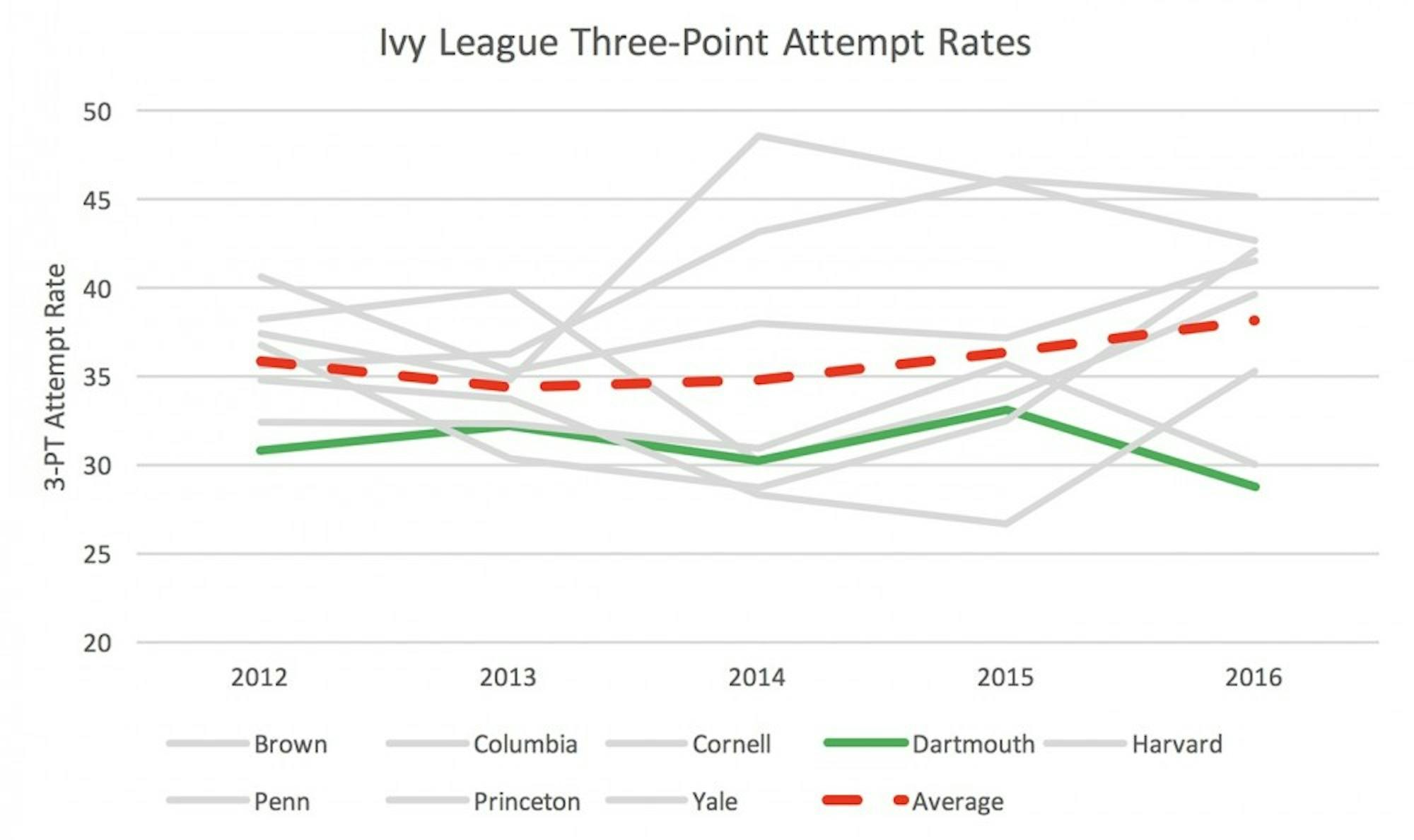

In this respect, Dartmouth has been reluctant in embracing this key tenet of the basketball analytics movement relative to other Ivy League teams. Consistently below league average in each of the last five years, the team has endured a harmful downturn in 2016. Sinking to a five-year low of 28.8, the tendency starkly diverges from the league average trend, which now stands at 38.1. Furthermore, this season has also seen the Big Green post the second highest midrange jumper consumption, another sign of a poor shot-taking diet.

“We would shoot more threes if we had better 3-point shooters,” Cormier said in emphasizing the personnel aspect of this issue. “Everything depends on the talent I have. If I had a talented group of 3-point shooters, I would definitely be more apt to shoot the three. I [have] an inside-out philosophy, I’d like to attack inside and then out, but if I had a lot of great three-point shooters that certainly would change.”

While higher 3-point shot-taking does not invariably lead to more success, a greater focus towards it is vital for a healthy offense in light of the sport’s current era. Even in the Ivy League, with the exclusion of the outlier of Yale University, a fairly strong correlation results from winning percentage and 3-point attempt rate.

Perhaps the brightest spot to emerge in the 2015-16 season for Dartmouth was the ascendance of Evan Boudreaux ’19. Tying the all-time conference record for the most Ivy League Rookie of the Week honors, the freshman has risen to new heights during conference play in averaging a double-double at 19.7 points and 10.6 rebounds per game. Two notable aspects of his game have stuck out in 2016.

Few equal Boudreaux in terms of a near-unstoppable ability in driving to the hoop and generating results. If he doesn’t convert a shot after penetrating the paint, he consistently and seemingly naturally draws contact at the rim — the freshman leads the Ivy League in made free throws and trips to the line.

Secondly, Boudreaux has cultivated an overpowering presence on the boards, fueled by physicality and anticipation, a talent that’s simply striking at times. Near the top in every rebounding statistic in the conference, the freshman has dominated the defensive glass especially with a second-best Ivy defensive rebound percentage.

“I’d say the biggest thing we need to get from him [moving forward] is we have to be able to put him on the opponent’s best big man at times defensively,” Cormier said. “He’s gifted offensively, we have to get him to pay more attention to the defensive side, and improve there so he’s a complete basketball player. He’s shown at times he can do that. We ask him to do an awful lot, but we’ll try to stretch him a little more so he can be a totally complete player.”

A composite measure for his contributions in win shares ranks Boudreaux as the sixth best player in the conference — in only his freshman year, with everyone on the list above him a junior or older. With all of these merits under his belt, Boudreaux should unquestionably receive the Ivy League Rookie of the Year. If that does happen, it would be the second consecutive year in which a Dartmouth player will have won the award after Miles Wright ’18 did in 2015.

This then begs the pressing question of whether the team’s trajectory should only slant upwards. First and foremost, Boudreaux and Wright need to prove that they can mesh well together moving forward, and that their styles are compatible, as well as continue to make individual strides.

Just as crucial will be the pieces that surround them. Size and an interior presence will once again mark a concern entering 2016-17, as half of the team’s frontcourt players are seniors.

The backcourt offers many more interesting options, starting with Taylor Johnson ’18, the team’s third-highest scorer in Ivy play during which he elevated his game and displayed a superb 3-point shot. Among the team’s 11 regular rotation players that have played at least 200 minutes this year, the sophomore had the highest true shooting percentage — a shooting efficiency metric that takes into account three’s and free throws — on the entire team, an amazing feat considering he’s a guard. He also did so while commanding relatively few offensive opportunities, as measured by just a seventh-highest usage percentage.

The team will have to return its attention to a lack of point guard stability, but the development of some younger guards might address this issue. Cormier also notes that he expects to rely on incoming freshmen to help remedy this deficiency.

After losing a senior leader and one of the team’s best players due to an unexpected transfer, no one should have expected a rapid recovery in 2015-16 from the Big Green. Yet the team nevertheless showed signs of building a foundation that could prove competitive in the conference. Having two more years with some of the Ivy League’s brightest young talent in Boudreaux and Wright, and several more interesting pieces that surround the duo, Dartmouth should only improve from where it will end in 2016.