I recently published an op-ed about Evergreen.AI. I mostly agree with what I wrote, but I decided that couldn’t be the last word on my story of why I joined Evergreen. It wasn’t a lie, but it wasn’t the whole truth. I still think Evergreen deserves a chance, but only if students’ stories are driving it.

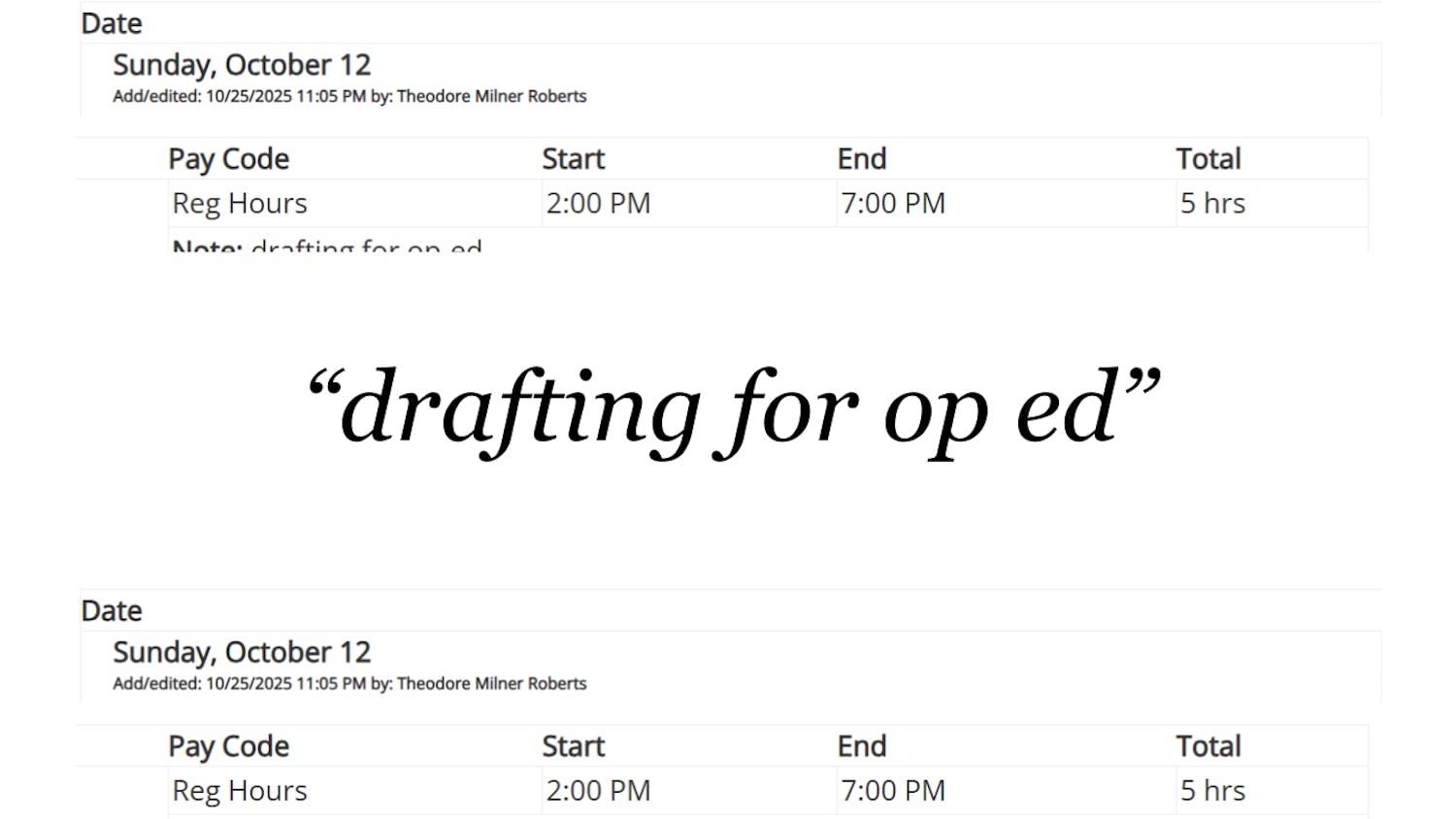

First of all, I want to be transparent about why and how I wrote that article in the first place. The College’s Office of Communications asked me to write it. Evergreen paid me to. I also thought it would look good on the AI ethics resume I have been working on. Looking back, I realize how hollow that motivation was. Though they told me there was no pressure, I allowed it to become a script because I was too afraid to speak up against the message of the professors and staff in charge of the project. These leaders are so high above the students and research coordinators actually creating the content that I have never met any of them in person after working on the project for six months. Even after all the rounds of editing, the College media team told me to “sit tight for now” while they reassessed whether my opinion was the most strategic thing for them to share. In the end, I am the one to blame for signing off on a statement that wasn’t really mine.

I want to make a crucial distinction here: I have immense respect for the research coordinators and directors of Evergreen. Instead, my frustration is with Evergreen’s hierarchical system. I slowly realized what I needed to do when I showed that first op-ed to my friends. I watched their polite but indifferent reactions; I heard how little the strategic messaging meant to them. I realized that in trying to protect the project’s image, I had stripped it of the very thing that could make it connect. I don’t want to hurt Evergreen; I want to help it find its voice. For that first op-ed, the College prompted me to write about the connection between Evergreen and my mental health. I want to be fully transparent this time.

When I came to Dartmouth as a freshman, I was desperate for connection. I missed my family. I did not want to end up lonely, so I threw myself into the social world as hard as I could. I went out all the time. I did my best to play the social games, but I made a lot of mistakes. Despite those efforts, I couldn’t escape this desperate feeling of disconnection, of not having found my people, of being misunderstood.

So I made an escape plan. I applied to fly across the ocean to do research in Denmark, then participated in an exchange program at the University of Copenhagen during my freshman summer and sophomore fall. I thought that by the time I got back, I would have new self-confidence and everything would work out. It did not.

Returning to campus my sophomore winter did not go well. I hadn’t seen anyone for six months, and it felt like all of my friends had gone through one of the most intense trauma-bonding experiences of their lives as they struggled through the humiliations of Greek life pledging. I was more alone than ever.

So, I threw myself into work. I told myself, “I don’t need them. I’ll show them.” I stopped going out, seeing friends or really trying to be social at all. I lived like this for the next year. Emotionally, it was soul-crushing, but to the outside observer, I was doing quite well. I remember the day I landed what should have been a dream internship. I wore the company merch around campus that day as a badge of honor, trying to fool myself into thinking all the sacrifices I had made had been worth it. I left for work during my junior winter and spring to escape the pain of being trapped on a campus that was so full yet felt so empty. When I got back, all I had to do was survive four more terms, one of each season, and then I was free. That’s when I joined Evergreen.

I had never really thought much about mental health before that summer. I was just looking for another tick on my resume and a way to pass the time. But as I worked, I was surprised to find myself learning. In our meetings, we were writing dialogues about common mental health problems that students have on campus, playing both the bot and the troubled undergraduate. I distinctly remember the first time I heard one of my peers share their dialogue on “behavioral activation,” which is the idea that when we are feeling down, we can improve our mood just by doing something we normally do when we are feeling well, even if we don’t in the moment. I decided, why not? The next time I felt the crushing loneliness I had been struggling with for years, I went for a run. And it helped.

I started making these little changes to my life based on the advice of my Evergreen peers. I reached out to some old friends and made some new ones. I started getting really into music again. For the first time in a long time, I wasn’t always feeling this cloud hanging over me while on campus. I was changing, or maybe just returning to my self. I think that I am now perhaps the happiest I have been in my entire life.

Evergreen has the real potential to help Dartmouth students. Even if it could go wrong, building this tool in the name of helping people is worth it. It’s worth it because it could get someone like me to wake up and just appreciate how lucky they are to be here with all the incredible people on our campus. If there’s a chance, then I say, let’s try.

But let me be clear: Evergreen only deserves this chance if we fundamentally change how it is being built.

First, we need to dismantle the invisible wall between students and leadership. It is impossible to create a tool for deep human understanding when the team creating it is disconnected. Students need to meet and regularly interact with the professors and staff in charge of this project — not just through Slack messages or middle managers, but face-to-face. We need a structure where every voice, from the freshman researcher to the tenured professor, can be heard.

Second, we must move from the hypothetical to the real. Right now, we write dialogues based on hypothetical scenarios, but hypothetical stories breed hypothetical solutions. We need to encourage the sharing of real stories — the messy, unpolished truths of our actual lives.

This requires leadership to create a genuine safe space. If the creators are afraid to be honest, the users will be, too. If they feel safe, they will share the kind of truth that actually heals. I am not writing this to burn Evergreen to the ground; I’m writing to save it from becoming just another well-funded, well-intentioned, but ultimately hollow initiative. I have immense hope for this project, but hope isn’t enough. We don’t need more oversight from above; we need the safety and autonomy to speak the truth from below.

Teddy Roberts is a member of the Class of 2026. Guest columns represent the views of their author(s), which are not necessarily those of The Dartmouth.