Over the past few years, Netflix has capitalized on people’s fascination with the macabre. From the 2015 hit “Making a Murderer” to “Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes,” “The Ripper” and then this year’s “Crime Scene: The Vanishing at the Cecil Hotel,” recent Netflix originals have focused on a darker side of human nature. On April 2, this trend continued with “The Serpent.”

However, the limited series of eight episodes is not Netflix’s true-crime pièce de résistance. The crime itself — or, in this case, a series of crimes — is enthralling. But the achronological representation of the crime is disorienting, the show’s concluding episodes appear lazily constructed and the series was lackluster overall.

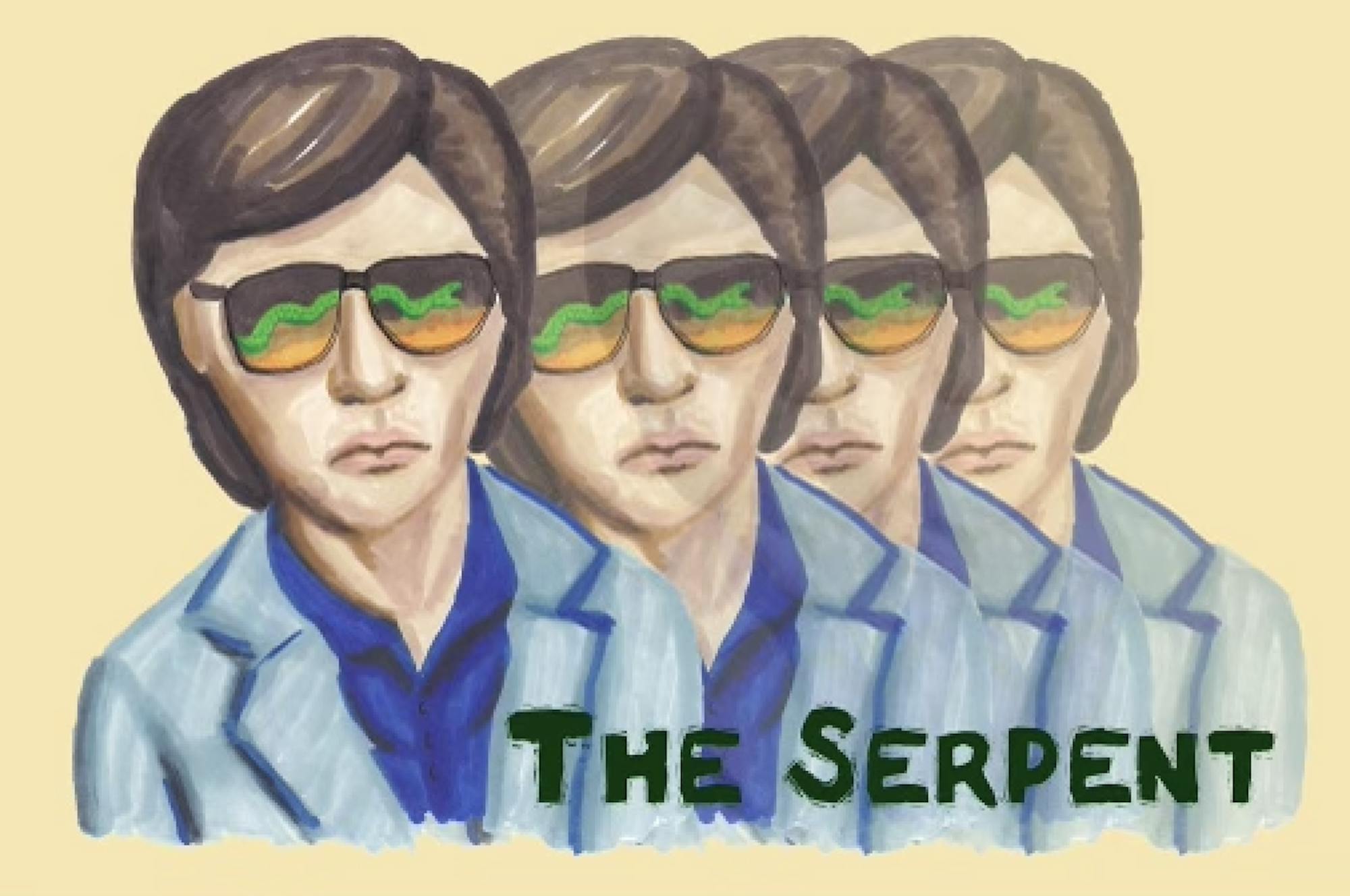

The eponymous criminal of the series is Charles Sobhraj — nicknamed “the Serpent” — as well as “the Bikini Killer,” played by Tahar Rahim. Currently rotting away with a life sentence in a Nepalese prison, Sobhraj is a sociopathic serial killer who committed heinous crimes in the 1970s. He began with petty theft, but his crimes eventually escalated to robbing tourists, jewel heists and, most notably, drugging and murdering Western travelers roaming the Hippie Trail of South Asia. An underreported and absurd story, set in such an interesting time and place, yields high expectations for its cinematographic retelling.

“The Serpent” does not grace its audience with a detailed and organized understanding of Sobhraj and his motivations. Viewers only learn about his background from tiny breadcrumbs scattered through a few episodes and an introduction to his mother in the sixth episode. Instead of elucidating his “mutt” background and “stateless” origins — Sobhraj was born in 1944 to a Vietnamese mother and Indian father in Japanese-occupied Saigon, French Indochina and only gained French citizenship when adopted by his stepfather, an Army lieutenant stationed in the French colonies — the show leaves most details murky to curious viewers who must then satisfy their crime-junkie inclinations via a rabbit hole of internet sources.

For most of the episodes, all that viewers know about Sobhraj is that he is a sociopathic murderer, has a vendetta against hippies for some reason that is never properly explained and manipulates his two sidekicks — his lover, Marie-Andrée Leclerc, and his errand boy, Ajay Chowdhury.

Further obscuring the details of this murderous threesome’s actions, the chronology of the show is presented as a messy collage of timelines. The show skips time periods every few minutes, moving between different weeks, months and years in the blink of an eye. “The Serpent” is at a loss when it comes to narrative coherence. While the modern filmmaking trend of playing with timelines can be done well, it is overdone here. As I sat watching, I hoped for a reprieve from time-jumps of “one year ago” to “seven years later” to “three months earlier.”

The sloppy timelines are forgivable early on in the show. The crimes are so unbelievably evil, the perpetrator so horrifically larger than life, that the structural flaws are overshadowed at the start. Sobhraj’s egomania is perfectly encapsulated in a confrontation with his mother: Sobhraj’s mother sharply admonishes, “You ought to be careful, Charles. You’re almost 33 now. Jesus Christ died when he was 33.” Sobhraj responds “I’m smarter than Christ.”

The original shininess of Sobhraj’s criminal operations in Bangkok wore off after the first four episodes. In the following four, the plot dragged, if not limped, along. Boredom kicked in at the halfway point. Viewers mostly follow Herman Knippenberg — the Dutch diplomat, played by Billy Howle, behind the investigation — as he painstakingly tries to piece together a case after the Dutch ambassador, the Thai police and most other legal authorities refuse to help him.

The final episode brought a bit of intrigue back, but also constituted a rapid dump of information that was clearly hastily thrown together by the producers. All at once, we learn that Sobhraj and Leclerc have fled to Delhi to steal from and murder more tourists to support their lifestyle and Sobhraj’s gambling habits, Interpol now cares about finding Sobhraj and Knippenberg is spiraling due to his obsession with the case. In the end, predictably, cockiness is Sobhraj’s Achilles’ heel. He attempts to poison more than 20 members of a tour group at once and is arrested by Indian authorities.

The details throughout the show, particularly the last episode, are exaggerated. In each episode, an animated serpent slithers over a sepia-toned map of South Asia. The concluding updates on what happened to each character in reality are helpful, but also are superimposed on the same map. Tying it all together is the soundtrack that is a bit too on the nose; the early 1970s hippie music comes across as cheesy at best.

There are a few redeeming qualities in the production, namely that the first couple episodes are attention-grabbing and therefore effective in introducing the characters and their crimes. Additionally, the styling is outstanding; all the 1970s-era outfits, particularly Sobhraj’s flare jeans and Aviator sunglasses and Leclerc’s halter tops, were on point. The settings are also stunning. Most of the show was filmed in Bangkok, and the backgrounds are lush and inviting. Knippenberg and his then-wife Angela Kane’s home is also beautiful, situated next to a pond of water lilies. Finally, Rahim’s acting throughout was captivating and convincing.

The producers must also be commended for their commitment to historical accuracy. The limited series is based on interview tapes from Sobhraj’s time in prison, but given that Sobhraj is a sociopath and pathological liar, there is reason to be skeptical of his narrative. At one point, Sobhraj even sold a French producer the rights to a biopic for $15 million, demonstrating his narcissistic obsession over legacy. As they never spoke to Sobhraj directly, the producers were tasked with balancing Sobhraj’s egotistical, and potentially skewed, account of the crimes with accurate information.

Originally, Knippenberg was the character I liked most because of his deep conviction for justice. Yet, even his character devolves as he develops tunnel vision for the case, though, and his wife leaves him in the end — although this may be a reflection of what happened in real life. Additionally, I longed for character development for Leclerc. She has great tragic potential — both a victim and an accomplice to a man she loves. And, of course, the central story missing from the series is the origin of Sobhraj’s deep resentment of hippies.

At least this story, which went relatively unpublicized for so long, has finally entered mainstream media. At the end of the series, the victims are honored, which does bring some sense of justice to the case. All in all, “The Serpent” falls short of being a successful true crime series.

Rating: ★★★☆☆