Just by looking at a charter school building in Manhattan, one can tell that they are not like New York City’s traditional public schools. Charter schools are funded with public money but privately run. The money that would support a student in a public school is instead used to support a charter school if they choose to attend one. In New York City, the 10 percent of students who attend charter schools are more proficient in math, learn to read at grade level much faster and graduate at higher rates than their public-school peers.

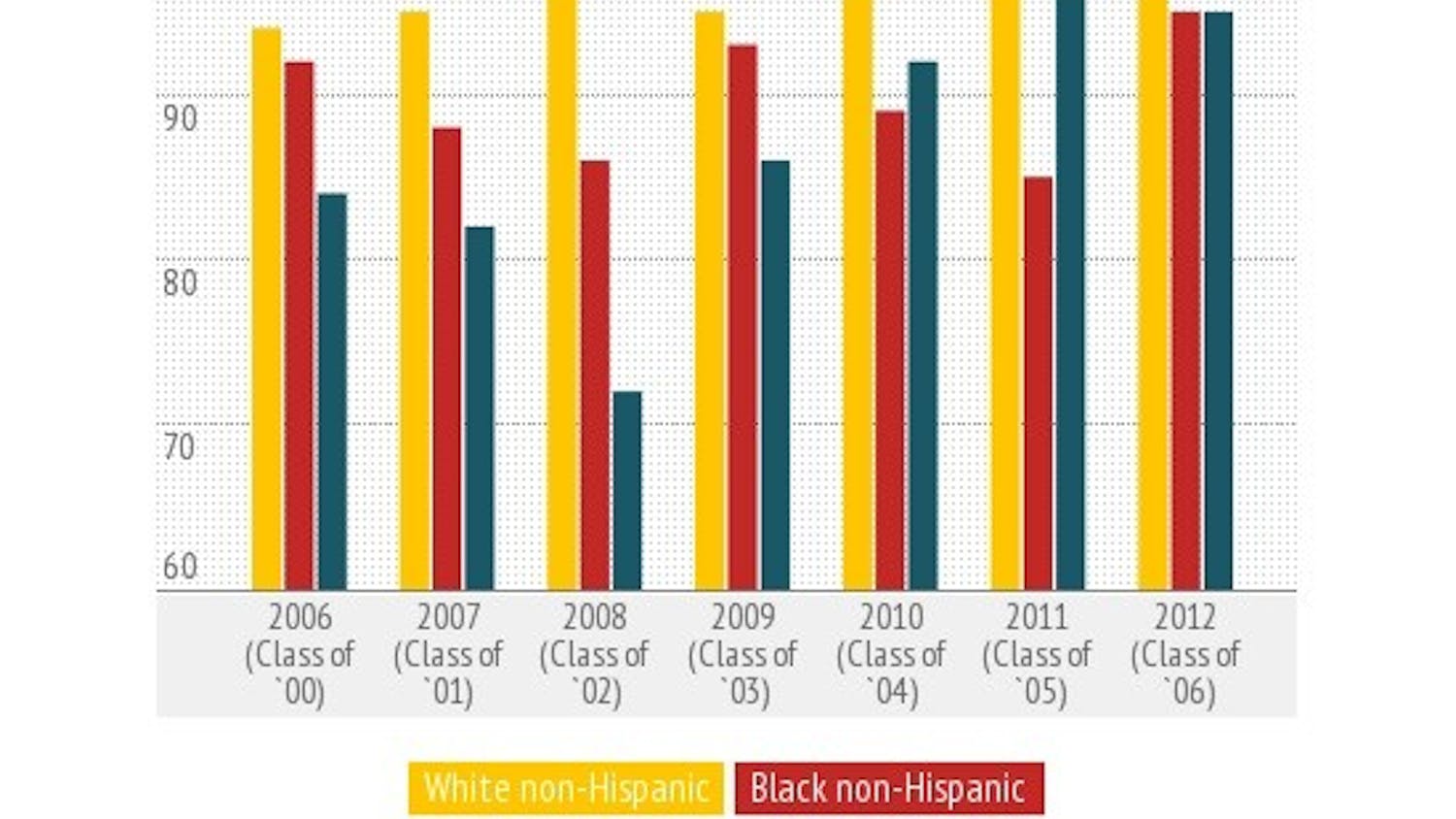

This is especially impressive because charter schools primarily serve the very kids who are most negatively affected by systemic inequality in our education system; more than 80 percent of New York charter school students are low-income, and 91 percent are African-American or Hispanic. According to one study, black students who attend charter schools in New York are four times as likely to score “extremely proficient” in math on state tests than their black peers in public schools.

In many ways, charter school buildings themselves are an apt metaphor for what charter schools represent. They are attractive and new, usually well-funded, well-kept and can be a beacon of light in neighborhoods where high school graduation rates are low. A mother whose son attended Success Academy, a charter school, called the day of his admission the best day of her life. When her son got into the school, she knew that he would have the opportunities she had never had because she grew up in the same neighborhood but attended a public school.

Charter school buildings themselves stick out like a sore thumb. Their shiny facades seem to highlight the drab crumbling exteriors of the surrounding buildings, often including public schools that look much more like prisons than places of learning. Charter schools don’t yet have the capacity to take in all of the kids that want to attend them. By law, they have to make admissions decisions based on the results of a random lottery. For the kids who don’t get in, that lottery can be heartbreaking. Looking at the luminous building across the street from within the walls of a dilapidated public school can feel like salt in a wound.

Though this system might feel unfair for the kids who don’t get to attend charter schools, it would be far worse to trap everyone in poor neighborhoods in failing schools, and to rob them of what is often their only opportunity for a better education and upward mobility. If we have a choice between sending all poor black and brown students to failing schools or letting some attend better schools while the rest remain in the public schools they would attend otherwise, the choice is simple. Our own desire for fairness and equity is not reason enough to force everyone to meet at the lowest common denominator. And, the more charter schools developed in a neighborhood, the more students will be able to attend them.

Critics worry that charter schools redirect funding that would otherwise go to public schools. The public-school network is a vast, national system, and it is beholden to teachers’ unions, some of the most powerful lobbying groups in the country. We spend more money per student on education than almost any other country, second only to Norway. And yet, we don’t reap the benefits of that investment — American students rank 25 out of 30 developed countries in math. Worse yet, we are on a downward trend; the generation in school today is predicted to be less literate than the generation that preceded it. Rather than continuing to spend more, we should spend smarter. When students go to charter schools, the money that taxpayers have invested in their education should go to charter schools with them.

Charter schools have problems. Some are too focused on standardized tests; others struggle with writing curricula and teacher retention. But American public schools in poor neighborhoods have those problems to a much worse extent. The difference is that charter schools are agile and adaptable. They can make changes quickly without spending decades navigating bureaucratic red tape. They’re incentivized to keep getting better. Unlike public school teachers, who receive tenure automatically after a certain number of years and become nearly impossible to fire, charter school teachers actually have to deliver in order to keep their jobs. And charter schools are in competition with each other for donations and students — if there are enough charter schools, students will be able to choose which to attend — so they drive each other to foster better communities and provide better education to students.

After decades of failed attempts to fix our public schools, it’s time to try a new tack. Charter schools aren’t perfect, but they are the best option for many poor students, and we should work to improve and expand them, rather than try to shut them down.