The average undergraduate GPA at Dartmouth during the 2017-18 school year was 3.52, an increase from 3.42 during the 2007-08 academic year, according to an internal College report obtained by The Dartmouth.

The report, presented in January by the Office of the Registrar to the Committee on Instruction and Committee on Chairs, also found that there was a “significant shift” over the previous decade, resulting in As becoming more commonly received than all Bs, B minuses and B pluses combined.

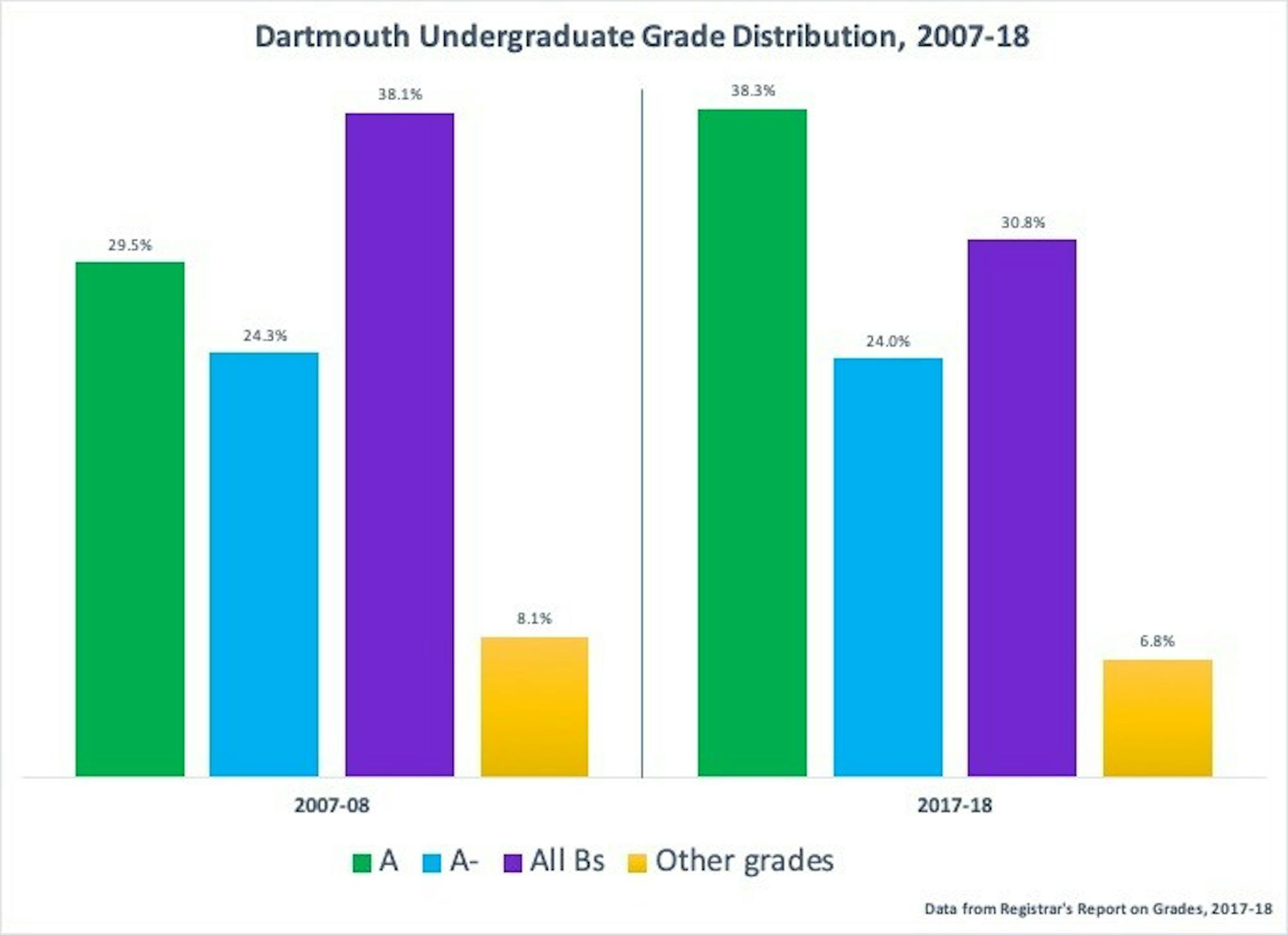

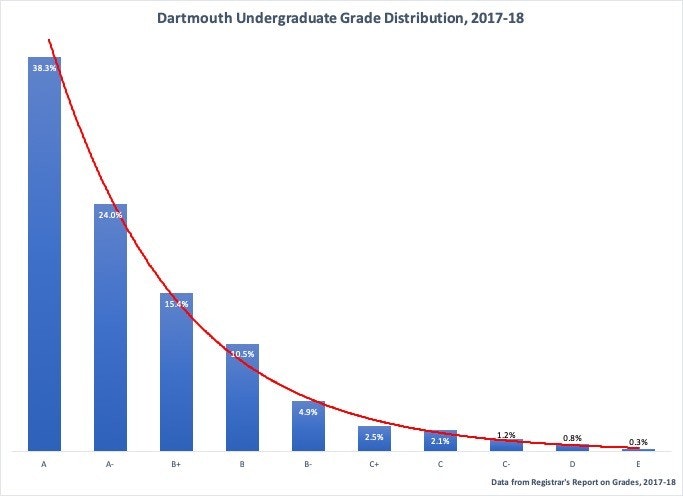

In the 2017-18 academic year, the single most common grade given was an A, making up 38.3 percent of all grades. This was an increase from the 2007-08 academic year, when As made up 29.5 percent of grades. Over the same period, the number of Bs, B pluses and B minuses went down. All three of those grades together accounted for 30.8 percent of the total grades awarded in 2017-18, compared to 38.1 percent in 2007-08.

Meanwhile, the number of A minuses awarded remained relatively consistent between the two time periods — around 24 percent — as did the number of grades below a C plus.

38.3 percent of undergraduate grades received during the 2017-18 academic year were As.

The percentage of class medians that are an A minus or above increased considerably over the past decade, from 53.8 percent in 2007-08 to 69.7 percent in 2017-18. The most common grade median, A minus, stayed constant at roughly 40 percent of all classes, while the proportion of A medians increased from 13.6 to 26.1 percent and the proportion of B plus medians decreased from 32.6 to 19.3 percent.

When broken down by class size, the report found that the number of As received relative to Bs increased in all three designations of “small” (one to 24 students), “medium” (25 to 75 students) and “large” (over 75 students) courses. In particular, small courses — which make up just over half of all courses at Dartmouth — see large numbers of As and A minuses. These grades made up 71.1 percent of all grades in such courses, compared to 53.4 percent of all grades in medium courses and 52.4 percent in large courses.

The report also found that first-years consistently had the best average GPA of all class years, although the senior class GPA increased from 3.36 in 2008-09 to 3.45 in 2016-17 — while other class years saw only marginal increases. Meanwhile, seniors consistently received the highest percentage of As, with 44.7 percent of all grades received by seniors in 2017-18 being As.

Click here to view excerpts from the report.

In response to written questions from The Dartmouth, dean of the faculty Elizabeth Smith wrote in an email statement that grade inflation has been “a topic of concern at multiple levels of education including secondary and post-secondary levels.”

“Discussion about the challenge of assigning grades and the root causes of grade inflation needs to begin with addressing fundamental questions about why we assign them and the meaning that specific grades have for students, faculty, employers, accreditors, and graduate schools,” Smith wrote. “Have the answers to these questions changed over time?”

Biology professor Mark McPeek, who chaired an Ad Hoc Committee on Grading Practices and Grade Inflation in 2015, said that there are “many, many serious consequences” to class grade increases, including lower student motivation.

“There is a [negative] correlation between the median grade in the class and what students report — how much time they spend outside of class working on that class,” McPeek said.

A report released by the Ad Hoc Committee in May 2015 acknowledged the existence of grade inflation at Dartmouth and found that the share of As and A minuses received increased from just over 30 percent in 1974 to 58.7 percent in 2014. The report recommended, among other proposals, that the College make its data on grades public, abolish the non-recording option and eliminate strict minimums on enrollment in undergraduate courses.

“At the current rate of increase,” the Ad Hoc Committee’s report said, “every grade given in every class to every undergraduate at Dartmouth in 2064 will be [an] A.”

McPeek said he believes there are two possible explanations for why high median grades occur: either every student in the class has mastered the course material perfectly, or the students haven’t really learned the material completely but the professor still gives out high grades. He said that if the latter explanation were true, it would demonstrate a failure on the part of professors for not holding students accountable for classes and homework.

Government professor John Carey, who became associate dean of the social sciences on July 1, said in an interview prior to his appointment that he sees grade increases as reducing professors’ ability to distinguish between student work of different qualities.

“I think given the amount of time and effort and intellectual blood, sweat and tears that we put into evaluating students’ work, it is important to recognize the distinction between work,” he said.

Likewise, government professor Michelle Clarke said that grade assignment plays a significant role in accurately assessing student performance.

“The most important thing we do is give feedback to students, evaluate the quality of their work and help them improve it,” Clarke said. “It’s harder to do that when there’s so much compression at one end of the grade spectrum.”

The registrar’s report showed considerable variation in the average grades given out by academic division. The average grade point in arts and humanities classes in the 2017-18 school year was 3.66, an increase from 3.54 in 2007-08. Social science classes saw an average grade point of 3.43 — an increase from 3.35 in 2007-08 — and science classes saw an average grade point of 3.35, an increase from 3.25 a decade earlier.

The course subjects with the highest average grades in 2017-18 were theater and Arabic, both with an average grade point of 3.83. Chemistry and mathematics classes had the lowest average grade points at 3.12 and 3.25, respectively.

Theater department chair Laura Edmondson said that her department’s high median was partly because the theater department largely grades on “engagement,” which she says is possible because of small classes.

“It’s not like a large lecture class where you can easily check out,” Edmondson said. “If they check out, we see it.”

Chemistry department chair Dean Wilcox said his department’s median typically has been lower than other departments. He attributes this to chemistry’s “unique situation” as the home for introductory pre-med courses.

“Those first chemistry courses are [students’] first physical science classes at college,” Wilcox said. “The material is conceptually a bit more challenging, a bit more abstract, a bit harder to grasp,” he added.

He also noted that many non-chemistry majors — including biology, engineering, earth science and occasionally neuroscience — have chemistry classes as prerequisites.

“You’ve got students who may not necessarily have any interest in going on in chemistry, but they have to take it for other goals,” Wilcox said. Combined with the large size of these classes — which gives them more weight in an average of grades — he said he believes these factors pull down the chemistry grade average.

Wilcox suggested that a potential cause of higher grades being given at the college level is because high schools are more effectively educating students.

“You took classes in high school that I probably never did,” Wilcox said. “You’re more advanced, perhaps, than earlier generations of students. I didn’t have the opportunity to take calculus in high school, but many kids that are interested in STEM come in already having had calculus.”

Dartmouth's average undergraduate GPA increased by 0.1 points over the last decade.

While the registrar’s report quantifies a recent GPA rise at Dartmouth, the College’s steady grade increases are comparable to those of peer institutions. A 2014 analysis by The Economist magazine showed that Dartmouth’s average GPA in 1950 was roughly 2.5 — right between a C plus average and a B minus average — and has gradually increased since then. That analysis found similar grade increases by comparable trendlines at other Ivy League institutions. A recent report by RippleMatch, a job recruitment company, estimated the average GPAs at Ivy League schools based on data from student customers and found that Dartmouth ranks roughly in the middle of the pack — with Brown University, Columbia University, Harvard University and Yale University having higher average GPAs than the College.

In 2017, The Harvard Crimson reported that Harvard College’s median grade was an A minus and that, like Dartmouth, the most frequently awarded grade was an A. That same year, a survey conducted by the Yale Daily News found that 92 percent of Yale University faculty believed grade inflation was occurring at that institution. The Daily News also reported that the mean course grade at Yale increased from 3.42 in 1998-99 to 3.58 in 2011-12, similar to Dartmouth’s GPA increase from 2007-08 to 2017-18. Even Princeton University, which implemented strict university-wide grade deflation policies in 2014, saw its average GPA increase by 0.026 points from 2017 to 2018, according to The Daily Princetonian.

College spokesperson Diana Lawrence declined to answer written questions from The Dartmouth about the subject of recent grade increases at the College.

“Grading and the related issue of grade inflation are the purview of the Dartmouth faculty,” Lawrence wrote.

Student Assembly president Luke Cuomo ’20 said it is well-known that grade inflation has occurred at Dartmouth and other schools over a long period of time. But he said that the problem is not necessarily a “dire” one and that taking actions to reduce grade inflation, such as setting limits on the number of As that can be given out per course, could yield negative consequences, especially in potentially exacerbating problems such as mental health, anxiety and academic stress among Dartmouth students.

Cuomo also noted that while students may intentionally seek out easier classes, they still have to be conscious of how that might later appear.

“On your transcript, if it shows you’ve only taken classes with A medians, that’s noticeable,” Cuomo said. “And in a way I think that drives certainly some people to diversify their classes and show that they aren’t only taking layups three times a term.”

In interviews with The Dartmouth, two recently-graduated students from the Class of 2019 whose GPAs placed them at or just below the top of their class expressed mixed feelings about the issue of grade inflation and the extent to which it is a problem at Dartmouth.

Christine Dong ’19, who earned an economics degree and was a class salutatorian, said she believes grade inflation occurs at Dartmouth, but said it may be a “necessary evil” because college is a path to employment and employers for competitive positions often have minimum grade thresholds when hiring. She also described grade inflation as a “chicken and egg” problem in which students might seek classes with higher medians, leading professors to offer such courses so students will sign up for their classes.

Class valedictorian and biology and economics double major Anant Mishra ’19 said that while he does not feel he personally experienced grade inflation at Dartmouth, he thinks grading practices can sometimes benefit the lowest performers in a given course because professors feel a responsibility to ensure they do not fail, especially in science classes with lower medians.

Mishra said that it is possible higher grades are simply a reflection of increasingly more talented and academically prepared students being admitted to Dartmouth each year, though that may be a reason for professors to change grading practices.

“Every year, Dartmouth students are more academically apt and [there are] better and better classes every year,” Mishra said. “I do think Dartmouth professors should adjust their testing and methods of examination to reflect that increased aptitude.”

On the whole, however, Dong and Mishra said the issue of grades and academic difficulty should be considered in a larger context.

“I think the value of a Dartmouth education is not just what you learn in a classroom, but the people you meet and the friendships you make,” Dong said. “And if I was in 100 percent rigorous classes every term, I don’t think my friendships would be as strong.”

Debora Hyemin Han contributed reporting. Peter Charalambous and Anthony Robles contributed.

Correction appended (July 26, 2019): The original version of this article stated that Dong said students might seek classes with lower medians. She said students might seek classes with higher medians, which is why professors may offer such classes.