Bruce Etling, director of the Internet and Democracy Project at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University; Elham Gheytanchi, a sociology professor at Santa Monica College; and Evgeny Morozov, a fellow at Georgetown University, presented information about the impact that social media has in the context of protest movements.

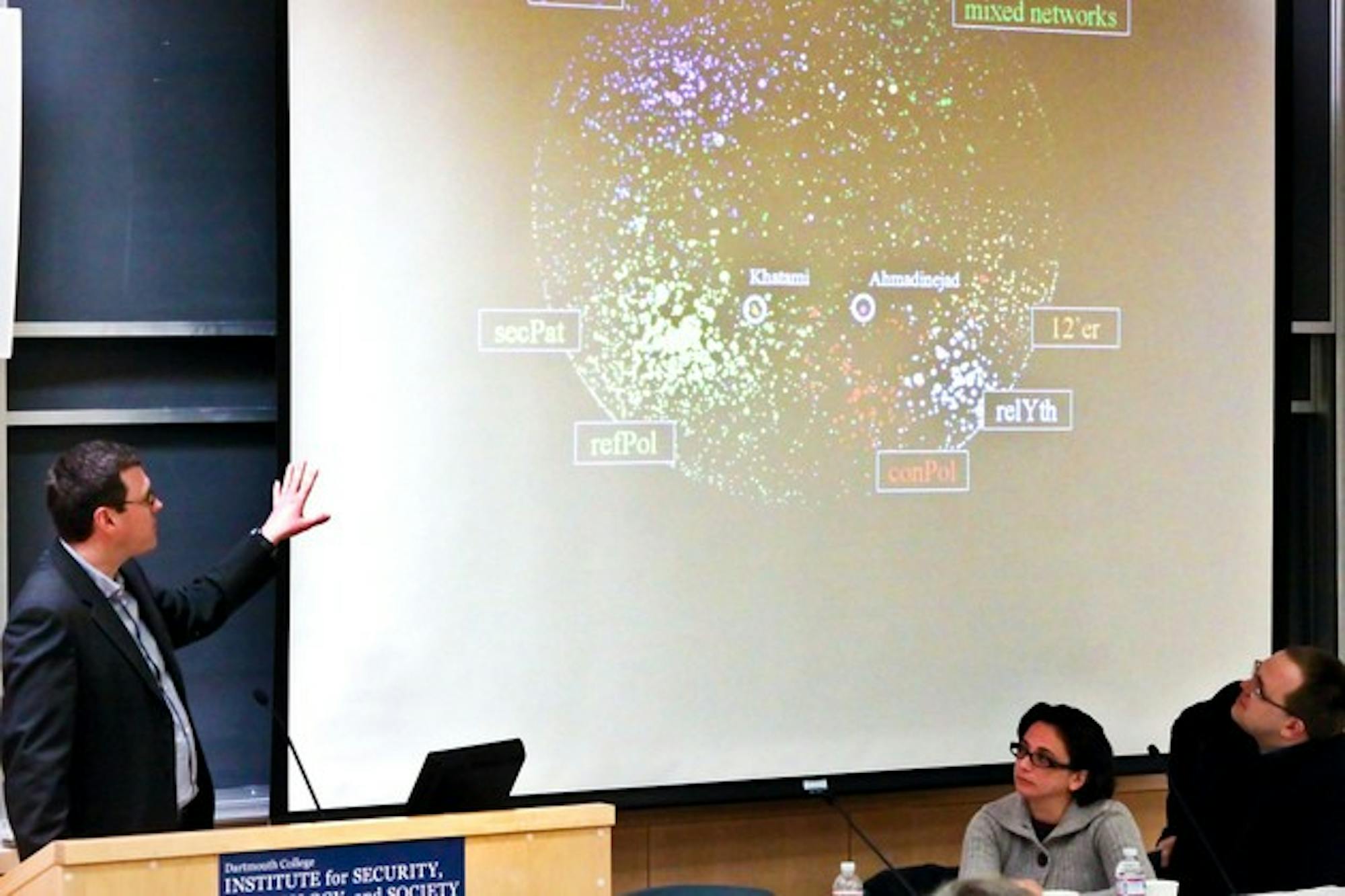

The Internet and Democracy Project began by observing anecdotal evidence of technological influence on protests and later shifted its focus to a more analytical examination of the blogosphere, Etling said.

"I want to introduce this concept of Newton's Third Law of the Internet,' that for every action there is an equal amount of reaction," Etling said.

While blogs may represent members of a population pushing for change, research shows that more conservative groups also have an online presence, Etling said.

Authoritarian countries are generally less successful when filtering information than the international community generally believes, he said. Roughly 10 percent of Iranian blog content is successfully blocked by censors, according to Etling.

"Really the crudest reactions are in Burma, where they simply shut down the Internet," Etling said. "But it is interesting that even in Burma, they didn't leave [the Internet] down for very long. A potential explanation is that the Internet has become so ingrained in people's lives that the more they shut it down the more push back they are going to get."

Whether protestors are able to influence decisions through blogs is hard to determine, he said.

Gheytanchi, who focuses her work on the protest movements in Iran, said the non-violent nature of Iranian protests increases the significance of social media in conveying political messages. This has incited a controversy over the control of social media outlets, which are often intertwined with politics, she said.

"Because of the lack of strong civil societies in Iran, newspapers and magazines have acted sort of as political parties," she said. "That's why many journalists end up going into the political arena, and vice versa."

New social media plays a key role in the political scene in Iran, Ghaytanchi said. The increased use of technology in Iran has resulted in changes including the empowerment of the individual, a change in the way the international community sees Iran, an improvement in transnational ties and a better means of influencing leadership, she said.

The government, however, is using technology in its own way to counteract the protests by taking images published online and using them to identify protestors, she said.

"So far we know [technology] has changed the way that politics is done in Iran, but we also know that the Internet, in and of itself, can only be a tool," Gheytanchi said.

Morozov's studies of the impact of technology on the effectiveness of protests has led him to develop a more pessimistic view of technology's power to empower protest movements, he said.

"I started as a very cyberoptimistic character," Morozov said. "I started noticing that in some of the contexts we are working in, the situations are actually getting worse, not better."

For blogs and social networks to become effective in organizing protests that can actually challenge the government, they need to become private sites, he said.

"The moment they become public, they actually become less useful to activists," he said. "There are many ways that has nothing to do with technology that the state can use to achieve its means. The fundamental foundations of politics and international relations haven't changed that much."

Morozov did acknowledge some positive impacts of technology.

"I think that there are many interesting political and social implications ranging from offering entertainment to shaping nationalism to facilitating not only national but also international and inter-religious dialogues," he said. "[But] we still have very poor understanding about what intelligence the government can draw from social networks or how much evidence they can draw from [Twitter]. All these questions need to be asked before we can push social media as a protest medium."