Chemistry operates both on the micro level through the study of molecules and a macro level in the analysis of substances, Hoffmann said. These two definitions of chemistry are often confused in scientists' minds.

"[Scientists] manipulate substances, but they talk as if they are manipulating molecules, which they are at some level," Hoffmann said.

Chemistry also involves the study of both simple and complex molecules. While a simple molecule may look beautiful, the most important substances, like the hemoglobin protein found in red blood cells, are aesthetically unattractive because they are complex, Hoffmann said.

"I feel guilty because these simple molecules, they've got a beeline into our soul," he said. "These other proteins look like clumps of pasta congealed out of primordial soup."

Hoffmann said he believes human beings instinctually prefer simplicity.

Tension in chemistry also arises from molecules' ability to cause both harm and benefit, Hoffmann said. Morphine, for example, is almost chemically identical to heroin, Hoffmann said. Ozone, when in the atmosphere, protects people from ultraviolet rays, but is a pollutant closer to the earth, he said.

Hoffmann gave the example of medical treatments for children with cancer. Treatments for the disease were largely unsuccessful until chemotherapy was introduced, Hoffmann said.

"Yet out of the back doors of the same companies making these materials for chemotherap or if it's not these companies it's some other company coming out the back door is this," he said, showing a picture of chemical waste and pollution.

Because of such negative images of chemistry, many companies today are no longer using the word "chemistry" in their advertising, Hoffmann said.

Many members of the public believe that chemists "are the ones that make things go bang," Hoffmann said. As chemistry has developed from its archaic early stages to include quantum mechanics, organic and inorganic chemistry, the science has also lost popular appeal, Hoffmann said.

"One thing that I do think is interesting about alchemy, despite the charlatanry, was that it captured the imagination of the public and the private imagination among intellectuals and others in Renaissance Europe," Hoffmann said, describing the appeal of immortality or transforming a poor person into a rich one by making gold.

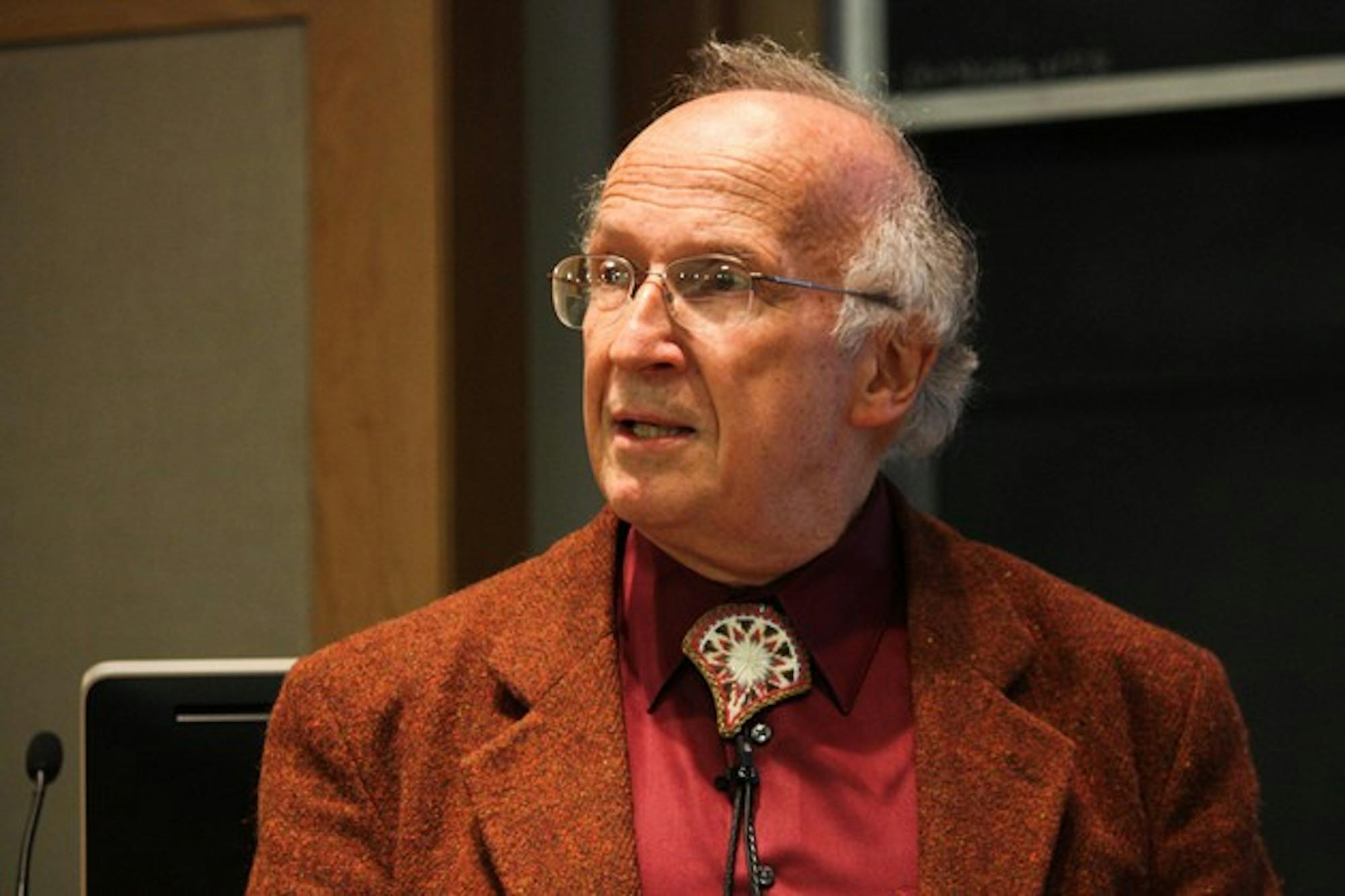

Hoffmann, in an interview with The Dartmouth, said he self-identified primarily as a chemist until 10 years ago when he became more confident in his writing. Hoffmann has published essays in science journals, as well as poems and critiques in art and literary magazines.

Hoffmann said he first became interested in the intersection between the humanities and sciences as an undergraduate at Columbia University. He was originally a pre-medical student, but after summer research jobs, "fell into" chemistry and courses in poetry and Japanese literature.

Hoffmann said science has remained foremost in his career, although he is now retired after 43 years of teaching introductory chemistry to undergraduates at Cornell University.

He is still continuing his research and is working to design new superconductors that will work under extreme conditions. Hoffmann was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1981.

Hoffmann's range of interests is reflected in his play, "Should've," which he read in the Bentley Theater last Wednesday. The play centers on the lives of three people, including a scientist who commits suicide after his research is used by terrorists to kill 600 people, his daughter who chooses not to publish her work on the flu outbreak of 1918 and her boyfriend, an artist who "would think nothing of putting Jesus in a toilet," Hoffmann said in the interview.

Hoffmann's most recent play "Something that Belongs to You" was inspired by his experience as a Jew born in what is now part of Ukraine just before World War II. His family was originally sent to a ghetto and later to a labor camp, from which he and his mother escaped. They immigrated to the United States in 1949. After Columbia, Hoffmann obtained a master's degree and a Ph.D from Harvard University.