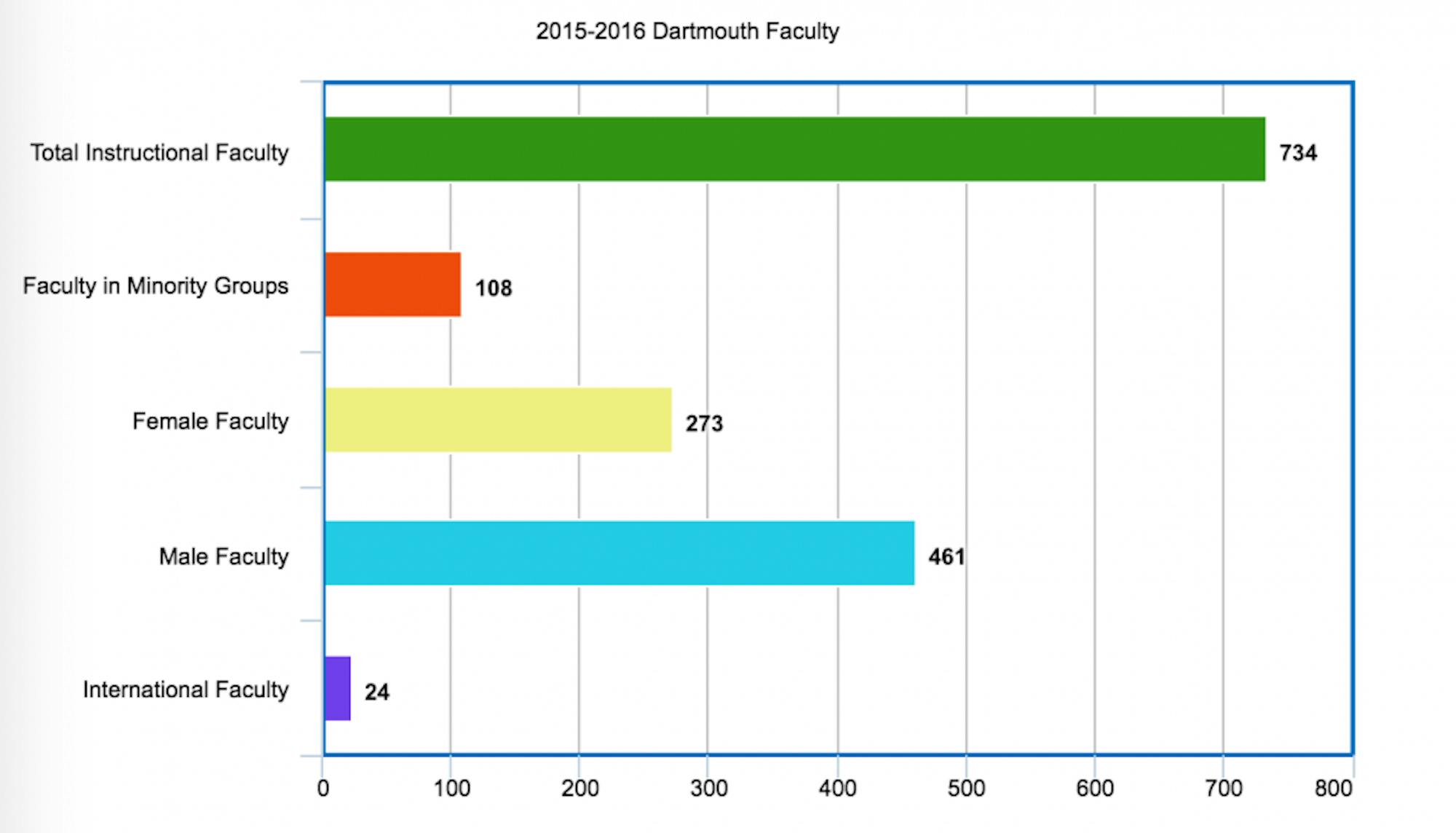

Faculty diversity at the College lags far behind that of the undergraduate student body. Whereas 37 percent of Dartmouth’s undergraduate population identifies as part of a minority group, only 14.7 percent of Dartmouth’s full-time instructional faculty identifies as belonging to a minority group, according to the 2015-2016 Common Data set published by the Office of Institutional Research. These numbers represent 1,597 out of 4,307 students and 108 out of 734 faculty, respectively, making Dartmouth the least diverse schools in the Ivy League.

Underrepresented minorities include Hispanic or Latino, African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander or two or more races.

According to the 2010 Dartmouth Fact Book, approximately 3 percent of faculty members were African American, 5 percent were Hispanic or Latino, 5 percent were Asian and 1 percent of faculty — four professors — were Native American. In 2010, 80 percent of the College’s undergraduate faculty were white. The remaining 5 percent were international.

Compared to 2010, the percentage of Native American professors has stayed the same, while the total number of African American faculty members has decreased. A 2015 breakdown of Dartmouth’s undergraduate faculty holds that 1 percent are Native American, 6 percent are Asian, 2 percent are African American and 4 percent are Hispanic or Latino. White faculty members are approximately 83 percent of the total. International faculty members make up the remaining 3 percent.

Fifty percent of the College’s undergraduate faculty have tenure. While few tenured professors are faculty of color, the numbers are proportionally reflective of total undergraduate faculty diversity. The 2015 Dartmouth Fact Book reports that 85 percent of tenured faculty members are white, 5 percent are Asian, 3 percent are African American and 4 percent are Hispanic or Latino.

At Dartmouth, Judith Byfield ’80 held both a tenured faculty position and chaired the women, gender and sexuality studies department. After 16 years as a professor at Dartmouth, Byfield left the College in 2007 to teach at Cornell University. She said that she left due to a number of reasons, including her need for a larger intellectual community.

“Tenure is a really complicated issue. There are benchmarks that people have to reach in order to get tenure, but I think that there are instances where the benchmarks keep moving,” Byfield said.

The changing requirements of tenure have resulted in a lack of transparency for the faculty involved, according to Byfield.

“There are times when people seem to have the benchmarks, but things like ‘Oh, which publisher published their book?’ become the deciding factor,” Byfield said. “It’s a very complicated process and at some point just leaves many of us a little lost as to how to even advise and mentor junior faculty since it is less clear than you would imagine.”

A lack of faculty diversity, Byfield said, also places additional burden on faculty of color, because they are often tasked with student mentorship, committee work and other miscellaneous responsibilities. The unique demands that come with being a minority faculty member, she said, can lead to feelings of “intellectual isolation” at Dartmouth.

History professor Soyoung Suh also pointed toward the College’s physical isolation as a force that often exacerbates the experience of minority faculty members.

“Teaching Korean history in California or in Hong Kong has a different meaning than teaching it here,” Suh said. “It’s not geopolitical, but Dartmouth’s location itself makes it difficult for certain people to make their agenda available.”

Armando Bengochea is the director of the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship, which prepares several undergraduates from underrepresented groups to become professors. Government professor Lisa Baldez, who also directs the Dartmouth Center for the Advancement of Learning, attended Bengochea’s April 20 talk on minority faculty recruitment as a part of the Leading Voices series. At the lecture, Bengochea cited how students could expose inadequacy within university policies toward faculty diversity.

Baldez, recalling how numerous protests on campuses across the country have erupted over the issue of diversity, said that people are becoming increasingly aware of problems like faculty diversity.

“That has mobilized campuses to do more on this issue,” Baldez said. “What I see happening at Dartmouth is a much stronger commitment from faculty and the administration on this issue and some real intentional efforts to change the situation.”

The Dartmouth Center for the Advancement of Learning focuses on teaching and learning.

“Faculty recruitment is not explicitly in our mandate, but teaching is a big part of what faculty do here,” Baldez said. “The way that we come at it is by talking about diversity and inclusivity in the classroom. For example, we have had a series of lectures focusing on disrupting bias in the classroom and faculty are enthusiastic about these sessions.”

Student Assembly president-elect Nick Harrington ’17 said that he hopes Student Assembly will be able to play a positive role in faculty diversity and inclusivity on campus.

“We can hopefully use the course evaluations or some other mechanism to show to what degree professors are acting as those mentors to students. It is something that is somewhat touched upon in the course evaluations but not enough,” he said. “The ultimate goal is to take the input that is given for the tenure track process and assure that students have a real input there.”

Harrington also mentioned how important it is for the College to not only to have the numbers they need, but put an infrastructure in place within the community so minority faculty members can thrive at Dartmouth.

To Byfield, faculty diversity remains a problem at Dartmouth partly because actions toward making change have not necessarily followed the stated goals.

“At some point there needs to be an honest conversation about what Dartmouth professes and what Dartmouth actually does,” Byfield said.

Dartmouth has the lowest minority faculty representation in the Ivy League at 14.7 percent. At Yale University, 488 out of 1,635 faculty members identify as a member of a minority group, ranking as the most diverse University in the Ivy League at 30 percent. At Columbia University, 981 out of 3,876 faculty members identify as a member of a minority group. Its 25 percent minority population places Columbia at the second most diverse school in the Ivy League. Twenty-three percent of Princeton University’s faculty identify as members of minority groups, which results in 270 out of 1,172 faculty members. Brown University has a 19 percent minority faculty population; 167 out of 885 faculty members at the university identify as a member of a minority group. At the University of Pennsylvania, 382 out of 2,085 faculty members, or 18 percent, identify as a member of a minority group. Cornell University’s minority faculty members make up 367 out of 2,141, or 17 percent, of its faculty. The Harvard Common Data Set has not been published for the 2015-2016 academic year. The 2014-2015 report states that at Harvard University, 370 out of 2,012 instructional faculty members identify as members of minority groups. This accounts for 18 percent of its teaching faculty.

Alexa Green is a junior from Boca Raton, FL. She is majoring in English, with minors in Arabic and Public Policy. After joining the newspaper her freshman winter, she served as a beat reporter covering Hanover & the Upper Valley. Following this position, Alexa became the associate managing news editor. Outside of the newsroom, she is a tour guide on campus, works for the Rockefeller Center for Public Policy, and conducts research in the English department. During her off term, Alexa worked for I.B.Tauris, an independent publishing house in London, U.K., editing and publicizing international relations and politics books. She is passionate about the ways in which policy, current events, history and journalism have interconnected roles in defining global issues.