During course election this fall, I was entirely preoccupied with figuring out how the timetable worked and deciding whether I truly wanted to take Spanish at 7:45 in the morning. The farthest thing from my thoughts was whether the professors who would be teaching me had tenure or not, but for those enmeshed in academia, standing for tenure is often one of the most pivotal moments in their careers.

The concept of tenure is traditionally seen as paramount to the preservation of academic freedom. According to Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Elizabeth Smith, who serves as chair of the CAP, Professors who hold tenure cannot be fired from their position without cause, allowing them to explore the questions they find most intriguing without the fear of termination. The Tenure Guidebook from the Office of the Dean illustrates that the idea of tenure originated in medieval European universities, but gained popularity in America during the mid-19th century as the result of conflicts between universities’ boards of trustees and their faculty. It also notes that in 1915, the principles of tenure were formally laid out by the American Association of University Professors, who called for the protection of faculty in both teaching and research.

According to the guidebook, the tenure system at Dartmouth developed along a similar trajectory. In 1834, the Board of Trustees dismissed Benjamin Hale, a chemistry professor, due to his external position as a minister of a Norwich Episcopalian church. Discontent with the Trustees quickly grew among professors as a result, and many called for the establishment of a tenure system. It took over a century, but in 1916, the faculty entered into negotiations with then-College President Ernest Hopkins and the Trustees to create a tenure agreement. In the summer of 1917, they formally established the system of tenure and created the Committee Advisory to the President, or CAP, which advises the president on tenure and promotions.

The system remained relatively unchanged until 1972, when the Board authorized half-time tenure appointments, allowing faculty on this track to receive tenure despite teaching only one to two courses per term. Then-president John Kemeny, cited in a January 1972 article in The Dartmouth, praised the plan’s ability to provide women educators with greater flexibility in balancing both their careers and potential family commitments.

Yet, despite this change, full-time tenure appointments comprise the large majority of current tenure cases. When these tenure-track professors are hired, they conduct research, teach classes and perform service to their departments, such as setting up colloquiums or recruiting PhD students, for six years. According to Smith, at the end of their sixth year, they stand for tenure.

To begin this process, they must first compile their research materials and present them to the tenured faculty of their department; these faculty also solicit letters of recommendation from both outside scholars and previous students. This compilation of materials is then evaluated by the tenured faculty of the candidate’s department; after they render a decision, the associate dean makes a recommendation based on both the materials and the department’s ruling.

The dean then presents the case at a meeting of the CAP that is attended by the six faculty members on this committee, as well as the president of the College. Based on the CAP’s vote, the president makes a decision and presents his or her recommendation to the Board of Trustees, who ultimately rules on whether to grant tenure.

Although faculty members recognize the necessity of this system, many are cognizant of room for improvement. Jewish Studies Program chair Susannah Heschel, currently on sabbatical in Boston, wondered whether tenure-track professors should be evaluated on their research contributions to their own, often narrow field of research, or whether it would be best to instead examine their contributions to the broader scholarly community. Furthermore, Heschel noted that the standards for tenure could be expanded to include the concept of collegiality.

“Scholarship just can’t exist on its own [...] we have to be in discussion and conversation with others,” Heschel said.

Smith mentioned that questions are often raised about the timing of tenure, as some faculty consider the current, six-year tenure clock to be insufficient.

“Sometimes it takes faculty longer to develop that body of work,” Smith said.

Additionally, Smith said that concerns are often raised about whether the expectations for tenure and promotion are clear. However, she defended the guidelines currently laid out in the faculty handbook, as the faculty conduct such diverse research that it would be unfair to create purely quantifiable metrics for tenure.

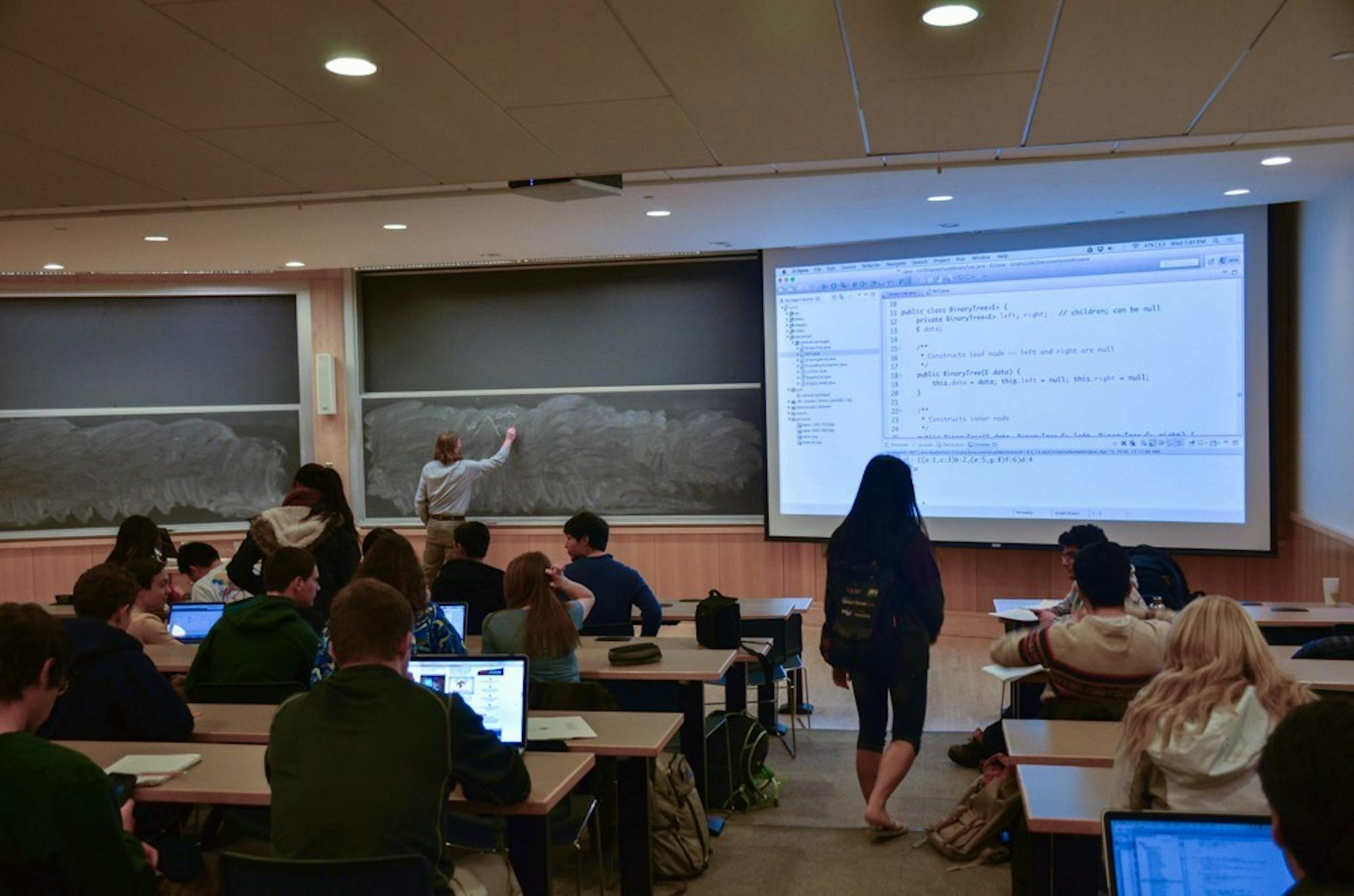

Computer science professor Hsien-Chin Chang, who is currently on the second year of the tenure track, raised concerns that tenure could strain student-professor relations.

“Whenever something bad happens between professors and students, students will always be concerned about whether they will be treated unfairly just because the other person has tenure,” Chang said.

He clarified that, at present, he doesn’t feel as though the school or its tenured professors are trying to cover anything up. Regardless, he suggested that open communication between students and faculty could preclude the possibility of these untoward circumstances.

“I think it would be really helpful to have these open discussions to talk about what [professors] actually do in our daily lives [...] to ease tension and hostility toward people who hold tenure,” Chang said.

In addition to these suggestions, perhaps the largest area for improvement involves the question of whether tenure is allocated fairly and with respect to diversity. Smith cited the results of a survey conducted at Dartmouth last year on whether women and faculty of color are disproportionately denied tenure.

“Mathematically, there’s no difference in tenure rates between women and men or between women and BIPOC faculty,” Smith said. “I can appreciate why there’s a narrative that perhaps women or BIPOC faculty are granted tenure less frequently, but data shows it’s not true.”

However, the study which Smith cited data from only focused on those who stood for tenure, disregarding those who are prevented from aiming for this promotion. For example, Heschel pointed out that women who want to have children might feel pressured to choose between their careers or their family lives.

“The whole process is set up around a man’s life,” Heschel said.

Despite these potential inequities, tenure remains an important component of both Dartmouth and the university system as a whole, a sentiment echoed by Smith.

“There’s that kind of security in terms of your freedom to explore any question that you want to explore,” Smith said.