This article is featured in the 2020 Fall special issue.

At the turn of the millennium, former College President James Wright and the Board of Trustees proposed an end to the fraternity and sorority system “as we know it.” Fifteen years later, College President Phil Hanlon said that without meaningful changes to the Greek system, the College would have to “revisit its continuation on campus.” Yet a walk down Webster Avenue confirms that Greek life at Dartmouth is alive and well — if a bit subdued this fall. What happened?

Both times, affiliated students organized to fight off the perceived threat to their social scene, vocalized their opinions about the benefits of Greek communities and drafted and implemented changes to the Greek system intended as compromises with the administration. And in both instances, the College administration backed down.

The Black Lives Matter protests this summer and debate over non-binary inclusivity in sororites this spring have brought yet another round of scrutiny to the Greek system — though, notably, no new initiatives have been announced by the College in response to renewed calls to examine Greek life’s troubled history.

Years of disagreement

Greek life at Dartmouth has been the subject of campus debate and scrutiny surrounding alcohol, sexual misconduct and inclusivity for decades. Records in Rauner Special Collections Library, for example, contain a ’40s-era flyer for a “Forum on Dartmouth Fraternities.” The panelists — one supporting Greek system retention, one supporting abolition and one supporting revisions — were asked whether chapters with “discriminatory charters,” or those that had policies prohibiting Black students from joining, should be eliminated and whether they “believe in the Dartmouth fraternity system.”

The same file contains a list of rules from 1946 “governing the entertainment of female guests and the use of alcoholic beverages,” warning fraternity members that relationships with women should be “maintained in accordance with the accepted moral code of our society” and that beer and liquor consumption should be “judicious.” These rules had to be followed if fraternities wished to reopen post-World War II, during which they were closed due to a lack of residents, according to an article in the 1986 Aegis yearbook.

1978 brought a faculty vote expressing support for the abolition of the Greek system. In response to the vote, the Trustees ordered the review of houses based on qualities such as “behavior,”“attitude” and “physical plant,” and multiple houses were threatened with derecognition or probation for violations. A code of “minimum standards” — covering everything from officer training to the acceptable height of the grass on fraternity lawns — was later imposed on houses.

“The options were clear — we could either move to abolish them or bring them back to a positive mode,” then-College President David McLaughlin told the Christian Science Monitor in 1985. The article noted that some of the problems, such as the deterioration of houses and leadership vacuum caused by 10-week terms, stemmed from the adoption of the 12-month academic calendar, which forced the houses to be open year-round, straining their resources.

In 1992, a task force reporting to the Dean of Students formalized sophomore fall as the first term students could rush and explicitly barred students from living in unrecognized Greek houses. Debate continued: Articles appeared throughout the 1990s in The Dartmouth, the Valley News, the Dartmouth Review and the progressive campus publication “bug” criticizing the Greek system for abetting sexual misconduct, “rampant bigotry” and elitism — or defending the system and rebuking critics’ arguments.

Student Life Initiative calls for Greek reforms

Wright was inaugurated as Dartmouth’s 16th president in the fall of 1998. Less than six months later, the announcement by Wright and the Trustees of a new direction for the Greek system embroiled Dartmouth in turmoil that made national headlines.

“The Greek houses didn’t have any warning that this was coming down the pipe,” Anne Mullins ’00, who was president of Kappa Delta Epsilon sorority at the time, said. “The news made it around campus, as I’m sure you can imagine, like wildfire.”

The announcement of the “Student Life Initiative,” which Wright said would lead to the end of the Greek system “as we know it,” among other changes to residential life, was seen as an existential threat by Greek leadership. It came the same week as Winter Carnival, and in response, Greek leadership canceled all planned events for the weekend, Mullins said. A pro-Greek rally on Psi Upsilon fraternity’s lawn replaced the traditional “keg jump,” and students gave speeches promising a defense of the social spaces they held dear.

“People were angry,” said Dean Krishna ’01, a member of Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity who served as Student Assembly president. “… [There was] that feeling [that] maybe they don’t understand us, this came out of nowhere.”

What made the student outrage strange, noted Janelle Ruley ’00, was that Wright’s letter to campus had said that the Greek system would be ended “as we know it,” not entirely. This only meant that the administration intended to make them “substantially coeducational,” as Wright put it in his letter to campus. Ruley, who supported abolition of the system, said that she was “surprised” that “what probably was intended to be innocuous wording really set off a firestorm.”

Mullins said that the vast majority of campus was against the still-vague plan, including self-proclaimed “GDIs,” or “God-Damned Independents” — unaffiliated students.

“There were a lot of students who were not affiliated,” she said, “but who had friends in the Greek system and who liked going to events hosted by Greek organizations.”

Krishna said that the outpouring of anger on campus may have caused the administration to unofficially “pause” the initiative. Simultaneously, Greek leadership shifted to “calmer” opposition, drafting letters and working internally. Over the following year, a College task force drafted proposals that reformed, but did not fully coeducate or abolish, fraternities and sororities on campus.

Recommendations included the removal of house bars, strict alcohol policies to attempt to discourage the practice of “booting and rallying” — vomiting up excess alcohol in order to continue partying — the hiring of non-student bartenders for registered social events, a moratorium placed on the formation of new Greek houses and rush was pushed back until sophomore winter.

“By and large, people understood there was a need for change,” Krishna said, adding that “the boot and rally culture really had no place in modern society at the turn of the century.”

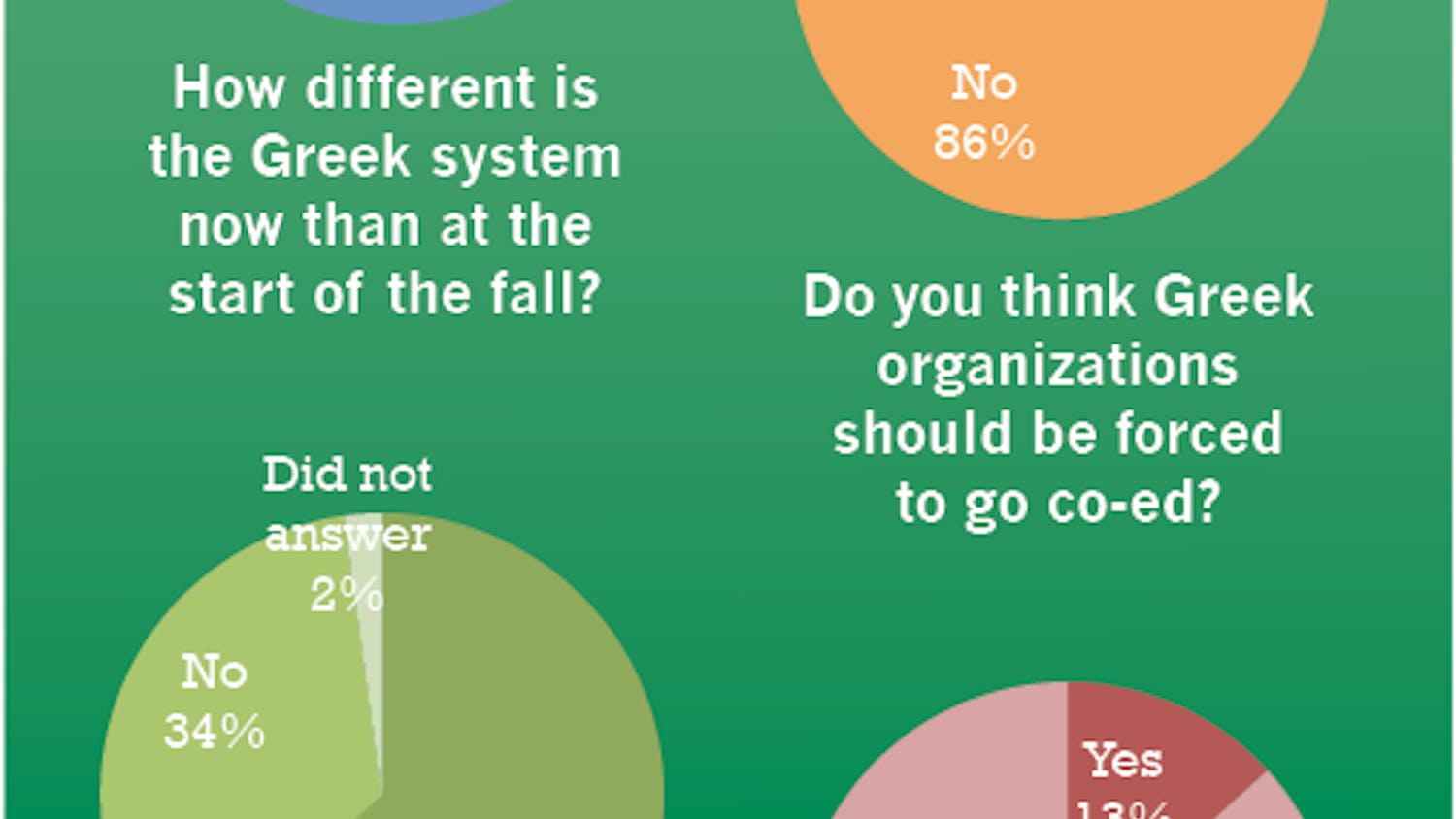

While opinion was split on the initiative overall, a poll conducted by The Dartmouth in November of 1999 suggested that students were open to reform in the areas of “alcohol and gender relations.” The faculty, on the other hand, felt it did not go far enough, voting again to support abolition of the Greek system in February 2000.

Overall, the initiative would aim to “eliminate the historical dominance by the [Greek] organizations of Dartmouth social life” by shifting to a less residential, more coeducational model, according to the steering committee’s report released in January 2000.

Permanent bars and taps were removed from houses in the fall of 2000, and other elements of the Student Life Initiative — including the inception of all-freshman dorms, the expansion of residential staff and the role of undergraduate advisors and the construction of additional dorms — were implemented in the following years.

But most of the changes did not materialize. In 2002, the administration replaced the minimum standards from the 1980s with a requirement that Greek houses submit yearly “action plans” that detailed how the houses would meet the principles of “scholarship, leadership, brotherhood and sisterhood, inclusivity, service and accountability.” Rush’s move to winter was reversed, as was the moratorium on new houses. In 2012, The Dartmouth Editorial Board, in calling for a “reassessment” of the Greek system, referred to the Greek portion of the SLI as a “failure.”

Another round of changes

The spotlight returned to the Greek system when Andrew Lohse ’12 made a series of serious hazing allegations — including vomit omelettes, kiddie pools of bodily fluids, chugging vinegar and “other abuses” — against Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity. Though they were first published in The Dartmouth and the independent blog Dartblog in January 2012, the charges against Lohse’s former fraternity eventually made their way to a cover story titled “Confessions of an Ivy League Frat Boy” in Rolling Stone magazine that spring.

“It was definitely a catalyst for a new round of scrutiny,” former Phi Delta Alpha fraternity president and member of the Alumni Council Taylor Cathcart ’15 said. He characterized his time at the College as a “slow bleed” for the Greek system, a period that saw more walkthroughs, stricter enforcement of rules and more houses being put on probation.

That is not to say that houses had not made changes prior to Lohse’s allegations. 2011 saw upgrades to houses, the creation of a bystander intervention program and a new process for addressing sexual misconduct claims in sororities.

But the graphic nature of the Rolling Stone article and the negative publicity it generated for the College began to spur action, Cathcart said. Faculty members spoke out about the need to end hazing, the Greek Leadership Council created a universal sexual assault policy that required education sessions and increased penalties for those found guilty of sexual assault and student activists noted a positive trend in campus discussions surrounding sexual misconduct. The GLC also implemented the freshman “frat ban,” which bars freshmen from entering Greek houses for at least six weeks of their first term on campus.

Within a year of his inauguration, Hanlon’s newly created Moving Dartmouth Forward initiative began to take shape. Administration members began pushing Greek leadership to take additional action to address issues around alcohol, sexual misconduct and hazing, and the MDF steering committee began considering reforms like the hard alcohol ban and the creation of alternative social spaces.

“There was sort of a sense … that, basically, the Greek system was going to need to do something itself, lest they risk the administration coming down with its own set of policies into which we had very little input,” Cathcart said.

Pressure mounted from other sources as well. The Dartmouth Editorial Board published a front-page editorial calling for total abolition in the 2014 Homecoming issue, writing that “our antiquated system cannot be reformed.”

The faculty, too, voted in 2014 for at least the third time since 1978 to express support for abolition. Biology professor Ryan Calsbeek, who proposed the motion in the most recent vote, said that his stance against the Greek system was influenced by his negative impressions from his college years and stories he had heard from Dartmouth students.

“A lot of my students would talk about some pretty horrific things that happened to them at those houses, or things that they witnessed,” he said, citing “really, really overt drunken behavior that led to sexual assaults.” Calsbeek declined to offer further specifics, citing his desire that students continue feeling comfortable coming to him in confidence.

Change eventually took two forms. First, the Interfraternity Council abolished “pledge term,” mandating that new members of Greek houses become full members immediately upon receiving a bid instead of having to go through an initiation process.

Second, Greek leadership published a “manifesto” with a litany of proposed reforms in the fall of 2014, including sober monitors, restrictions on hard alcohol, making it easier to expel students convicted of sexual assault, the appointment of faculty advisors and inclusivity trainings with the Office of Pluralism and Leadership. The petition eventually garnered over 3,000 signatures, and all the major Greek governing bodies agreed to its conditions.

“The administration seemed happy that we had put the proposal together,” Cathcart said. “It definitely led to, I think, a temporary detente in their crusade to eliminate the Greek system.”

When MDF was formally announced in early 2015, it contained some reforms that went further than the Greek leaders’ proposal, including a total ban on hard alcohol and mandatory sexual violence prevention education for all students. But like the SLI before it, MDF focused on residential life changes, including the creation of the house system. It did not threaten to end Greek life on campus — Hanlon even praised Greek leadership for the reforms of the previous term.

The following years saw the implementation of MDF’s various components, all of which are now listed as “complete” or “ongoing” on the initiative’s website. It also saw the derecognition of Alpha Delta fraternity and SAE for hazing and other violations.

Looking to the future

It remains to be seen whether the national wave of Black Lives Matter protests and subsequent scrutiny of Greek life on college campuses will lead to substantial changes at Dartmouth.

Abolition used to be a fringe position at the College. Just 16 percent of students supported it in 1999, according to The Dartmouth’s poll. Ruley, who supported abolition then, said that when her opinions were made public, her affiliated friends felt “surprised” and “betrayed.” Her and her friends’ public advocacy was later referred to as “admission of their anti-Greek sentiments” in a subsequent news article.

Today, abolition appears to be more mainstream. In 2014, the MDF steering committee reported that support for abolition was the most common feedback it received in its online survey, and a 2014 survey showed that opposition to abolition had fallen to 59% of students, down from 83% in 1999.

Calsbeek said that many of the faculty continue to harbor “misgivings” about Greek life on campus.

“I think the primary focus is on the well-being of the students,” he said. “When you see them show up in class looking devastated by a long night of hazing or too much drinking or something like that, you see the toll it takes on them academically.”

Both Mullins and Krishna said that their views on Greek life had changed since their time at Dartmouth. Mullins, who at the pro-Greek rally in 1999 declared that she would “fight tooth and nail” to maintain the Greek system, now believes “the administration may have been onto something.”

“I’m a professor now, and my perspective is a little bit different than what it was when I was a sorority president,” she said.

Mullins and Krishna agreed that the Greek system must do more to address inclusivity.

“Having your social scene dominated by single-sex male institutions — it’s the year 2020, and I feel like this can’t go on much longer,” Krishna said, adding that he felt similarly two decades ago and that “change has happened slower than I would have expected.”

Additionally, Cathcart, Krishna and Mullins all emphasized the need for communication between the administration and Greek leaders about changes to the system.

“The way the conversation was started [in 1999], unfortunately, students went on the defensive,” Mullins said. “I think, maybe, we could have had a more meaningful discussion about alcohol, diversity [and] hazing, and instead it sort of turned it into a tactical exchange with the administration, with Greek houses focused on survival.”

Cathcart, who emphasized his support for the continued existence of the Greek system, agreed that there is still work to be done on alcohol, sexual misconduct and inclusivity issues — but said that Greek houses are not the only places on campus that need to grapple with those.

“If the administration shows a willingness to actually partner with the fraternities, which they have yet to show in the last 15 years, then fraternities can be a force to drive social inclusivity, racial diversity and socioeconomic diversity on campus,” he said.

“[The SLI] certainly did spark a conversation, which was good,” Krishna said. “We should always be questioning whether our seemingly sacred institutions are the way that things should be.”