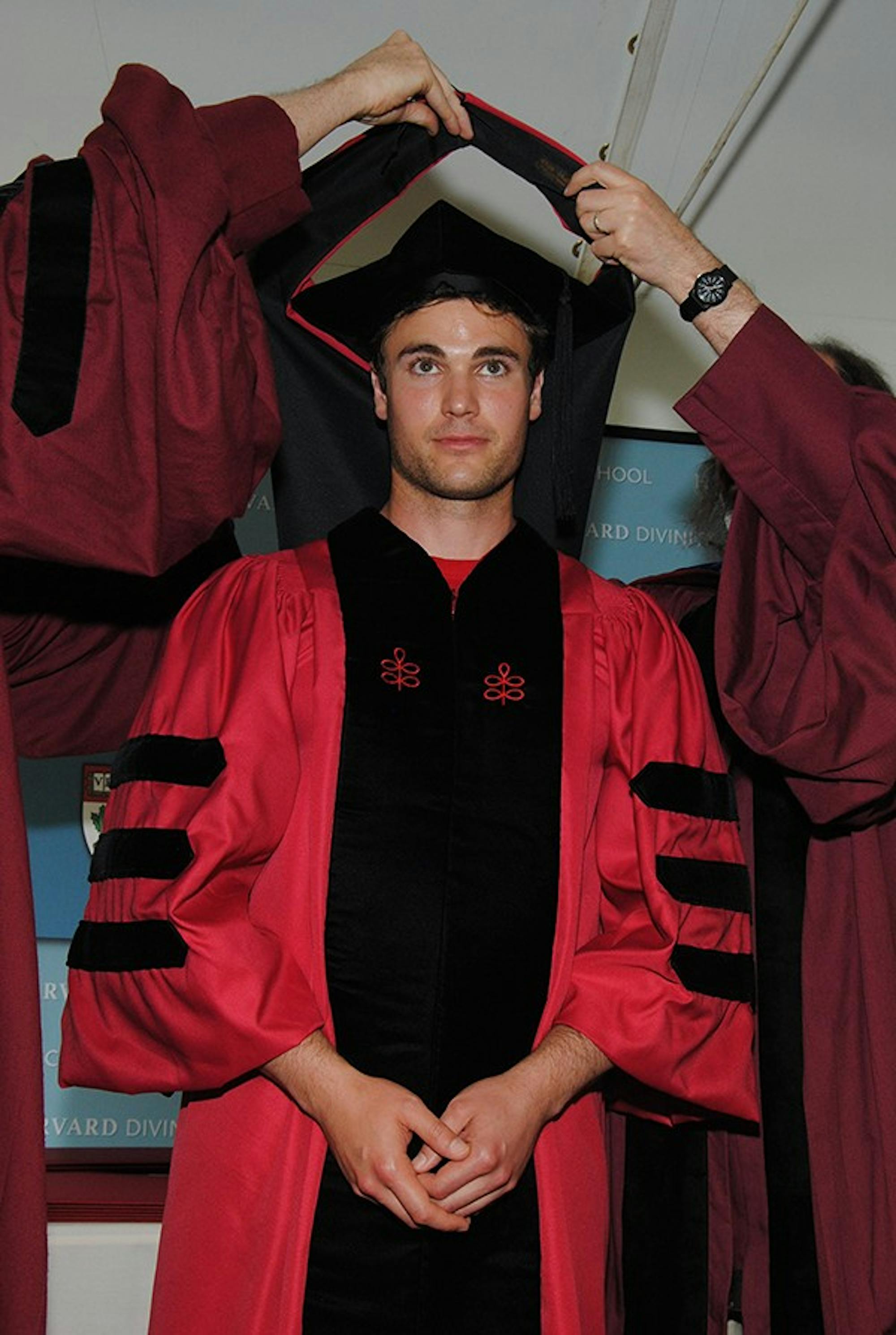

Growing up in Buffalo, New York, classics and religion professor Timothy Baker ’08 was interested in folklore, fairy tales and religion, a fascination that led him to take Latin in middle school and study religion when he came to Dartmouth as an undergraduate in 2004. After earning his B.A. in religion and Jewish studies, Baker earned both his master’s and Ph.D. in theology from Harvard Divinity School. Baker also has a diploma in Manuscript Studies from the Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies in Toronto, Canada. In his office in Reed Hall, Baker discussed how his interests in religion manifested and how religion and science can coexist.

How did your upbringing influence you?

TB: I was always interested in religion, and I was always interested in medieval stories, folklore, fairy tales, those types of things. And that interest was something I thought I wanted to pursue, graduating from high school. I had taken a lot of Latin as a middle and high school student and knew I really liked Latin, and knew that I liked it more than the Spanish I had taken, so I wanted to pursue something like that. So when I came here [as an undergraduate], I pretty quickly attached myself to the Latin program here and to the religion department, because that’s what I thought I liked, and it turns out I really didn’t like that kind of thing. So even though I spent quite a bit of my time taking courses — I would usually take four or five, sometimes six courses a term — and kind of bounced around to different departments, the core was in religion. So I took almost all the course offerings in religion, or at least as many as I could.

What interests you about it?

TB: What I study now is the practices by which one becomes God, and not the way one becomes God in a kind of arrogant sort of way, but the way one becomes God in the sense of humbling oneself and through that act of humility, or debasing, rising up – so descending to ascend, as the language goes. I find human spirituality fascinating, partly because I find human beings really fascinating.

Recently, there’s been a bit of a debate over whether science and religion can coexist, what do you think about that?

TB: I think it depends on what the goal of the debate is. If the goal of the debate is, at its very core, to discredit one another, then it is flawed at the outset. Those kinds of debates, I really have no patience for. I think that kind of black and white thinking, that binary, is divisive and not inclusive. I think that it just doesn’t do service to the historical realities of anything, really. Depending on the kind of religion, if we just took Judaism, Christianity and Islam as the three big ones, Judaism has always been quite comfortable with scientific advance, mostly because Judaism is, at its core, a religion of practice, as well as belief. The idea of Judaism is that you perform certain duties, certain actions, and thereby have respect for the divine. So what you believe or think or study, while important, is not something that necessarily infringes the way it would potentially infringe, if we’re thinking about those kinds of contemporary debates, on something like Islam or Christianity. There would be issues there, because those kinds of religions have certain kinds of faith-based statements, and I think that’s at the core of how some of these things go; you make certain claims of faith and therefore those must be incompatible with science. That tends to be what you see. That being the case, it’s just historically true that much of the scientific advances of the Greeks and the scientific advances of Arabic-speaking countries were maintained and championed by Islamic societies through much of the Middle Ages. It’s also manifestly true that a lot of the scientific advances in the West and in the East, when we’re talking about Christians, were maintained and upheld by the Church, with some notable exceptions. For the most part, there are ways in which the two intersect consistently and pretty necessarily; for instance, if you need to calculate when is the appropriate time to celebrate a holiday like Easter, you need to make solar and lunar calculations in order to do that.

There’s a fear that if we allow both perspectives to exist at the same time, there’s a kind of cheapening or denigrating one or the other. But that seems quite naïve to me, in that it should be possible — in fact, it seems to be the marker of an intelligent person —to hold the positions in one’s mind that one disagrees and agrees with. It should be possible, and it is possible, to entertain ideas that are both coincident with one’s thoughts and contradictory to them. In order to have debate, or to have inquiry, one has to be able to entertain multiple perspectives. It’s really quite dangerous to decide that one’s own perspective is the only one, or the more valid perspective, and that the other perspectives should be attacked or removed.

How did you become interested in Jewish studies?

TB: When I matriculated here, my freshman advisor was Ehud Benor in the religion department, and it just was one of those coincidences of fate, that he has both been and is a remarkable influence on what interests me and how I go about pursuing things, and we got along just famously. I found his way of experiencing and investigating the world to be something that really resonated with me. He is and has been enormously supportive of me, so I stayed with him as my thesis advisor. I stayed in touch with him over my time at Harvard, and I stay in touch with him now. Then, I went on the religion FSP, and I happened to be on it when it was led by Susannah Heschel, who is currently the chair of the Jewish studies program and who also teaches courses in Judaism — modern Judaism, the Holocaust, historiography, things like that. She and I got along really, amazingly well and I have stayed in touch with her ever since. It just so happened that the people with whom I studied here, particularly Benor and Heschel when it comes to the Jewish studies framework, their enthusiasm for their topics and my enthusiasm coming in for those kind of things, were such that I chose to be a minor in the program and then applied for a special interdisciplinary major in Jewish studies because I just wanted to do more with that sort of thing. It’s just awesome that students still get to have that experience with them because I can only hope to be a fraction of as good and influential to my students as they were to me.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.

Alexandra is a ’20 from New York and is unsure of what she plans to study, but has interests in neuroscience, geography, and human-centered design. Alexandra has written for The D since her freshman fall, and she enjoys meeting people and learning about various groups on campus through her articles.