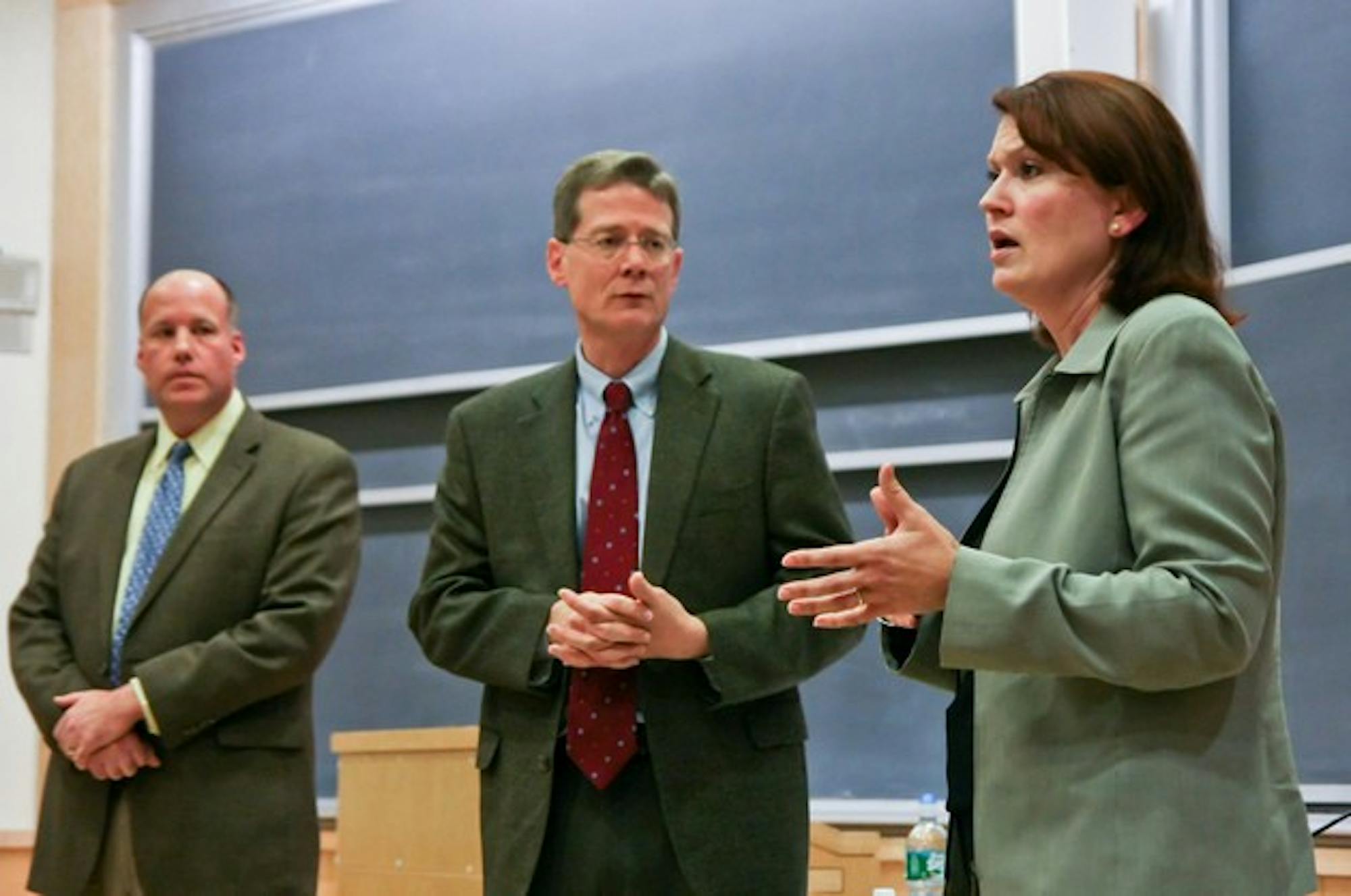

The talk, sponsored by the Dartmouth Ethics Institute, was part of a touring program, "Lessons Learned From the Failures of Others," organized by the University of St. Thomas. Hank Shea, a senior distinguished fellow at the St. Thomas School of Law, mediated the discussion. Shea has mediated more than 75 of these talks, in which white-collar felons most of whom he prosecuted share their stories to teach students about corporate ethics.

Nicholas Ryberg worked as a corporate human resource executive Koch Industries in the 1990s, at which time the company had a significant backlog of open positions and needed staffing firms to find qualified employees. Ryberg decided to start a headhunting firm under his wife's name to provide services for Koch.

"We thought it would be a good opportunity to grow a new business and get some extra income," Ryberg said.

To conceal his relationship with the company, Ryberg said he advised his wife to use her maiden name, a common practice for women in the search industry. The company eventually became a certified vendor for Koch Industries and began hiring employees for them.

As Koch's need for new hires began to decrease, however, Ryberg began submitting false invoices from the search company and approving payments from Koch industries.

"It wasn't registering at the time that this was fraud," Ryberg said. "It was just small things that I did, and later on, it was harder and harder to stop."

Ryberg advised his wife to start two additional companies to handle searches under different names.

Carolyn Ryberg said she eventually began to question whether the practice was "right or wrong," but that her husband remained unfazed.

"We paid the taxes for the business, and I thought I had full control over the situation," Nicholas Ryberg said. "You have to understand that I knew it was wrong, but my inflated ego gave me this sense of control."

The Rybergs continued the scheme until Nicholas Ryberg left Koch in 2003. They decided to start a staffing business called Management Recruiters, which initially appeared promising, Nicholas Ryberg said. A year later, however, Koch Industries discovered inconsistencies in its records and decided to file a civil lawsuit against the Rybergs for fraud.

"It was shocking, but I felt a sense of relief as well because it was finally out there," Nicholas Ryberg said.

The Rybergs' civil attorney told them that they could settle the case without acknowledging that they had committed fraud. Carolyn Ryberg began to suggest that they plead guilty.

"My conscience just couldn't take it, but they pushed aside my comments," she said.

As soon as the civil suit ended, the company pressed criminal charges, threatening the Rybergs with prison time. Carolyn Ryberg said that "reality began to set in" when the federal judge asked them for their pleas.

"I could barely say guilty for the third count," she said.

Nicholas Ryberg was sentenced in 2005 to 30 months in a low-security federal prison, while Carolyn Ryberg was sentenced to 24 months in a minimum-security prison. Since federal courts rarely stagger prison sentences, the Rybergs had to leave their two daughters, who were 15 and 16 years old, for the next two years, Carolyn Ryberg said. One of the daughters was sent to Los Angeles and the other was sent to Illinois to live with a family friend.

"The toughest thing was sending them on separate planes by my own hand," Carolyn Ryberg said.

The Rybergs said that they have worked to rebuild their lives after being released from prison. They also began working with Shea to share their story and show people the ease with which they fell into criminal behavior.

When questioned about the discretion Koch industries gave to its managers, Nicholas Ryberg refused to blame the corporation.

"I think the responsibility ultimately falls on my shoulders," he said. "It was those small bad decisions that I kept making and that led to this mess in the end."

While many workers feel pressured to complete a job, even if it involves cheating, Shea said he believes that cheating can be avoided if a company has capable leadership. Executives set the tone for a company based on how they act, and who they promote and hold accountable, he said.

"When I went to Koch industries, I didn't start off as a person looking for ways to make more money in any way," Nicholas Ryberg said. "What you practice you get good at, and I practiced small, bad decisions."

Shea said ethics education is essential for the nation's future. He cited a recent survey of students at 32 graduate schools that found that 56 percent of MBA students admitted to cheating at some point in their student careers.

Unethical decision-making can continue as students transition into the corporate world, making it important to address these problems early on in students' schooling, Shea said.

Correction appended (July 12, 2016):

The original first sentence of this article, "Nicholas and Carolyn Ryberg never planned to steal $1 million," inaccurately described the situation. The Rybergs agreed to a civil settlement valued at $1 million.

The original version of this article referred to Nicholas Ryberg as Nick Ryberg. His legal name is Nicholas Ryberg. All references to him have been corrected to his legal name.

The original article referred to a staffing firm as a recruiting firm.