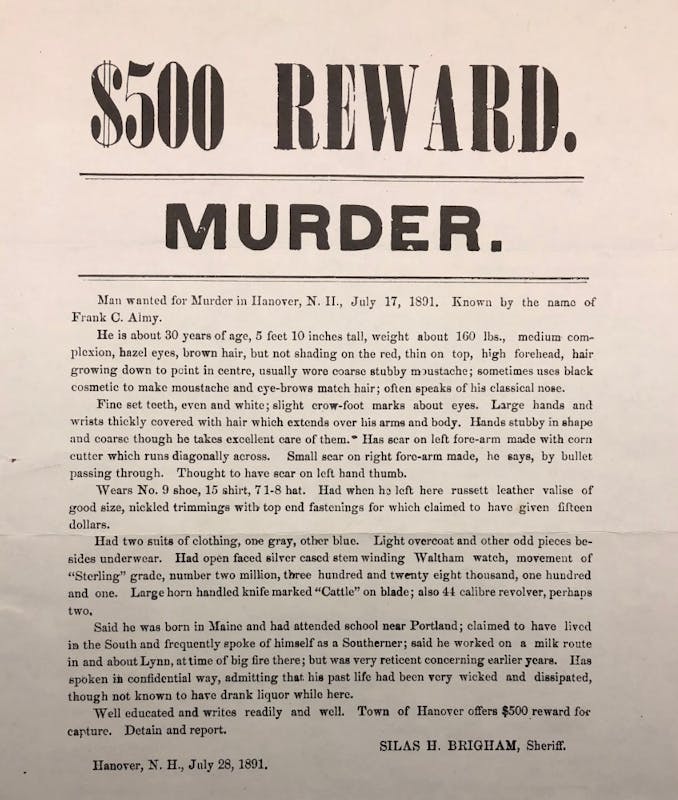

“Man wanted for Murder in Hanover, N.H., July 17, 1891. Known by the name of Frank C. Almy.”

The reward was $500; the crime, a gruesome murder that transpired just up the road from Dartmouth.

Andrew Warden, the richest farmer in Hanover, had hired Frank Almy as a farm hand in 1890. Almy and Mr. Warden’s daughter Christie soon started to spend time together, until Christie grew suspicious about Almy’s past. Despite his persistent attentions, Christie began avoiding Almy, and she even found temporary lodging in town until Mr. Warden dismissed Almy from the farm that spring.

Unbeknownst to the Wardens, Almy returned to Hanover in June 1891. On July 17, he hid in a hollow by the side of the road, waiting for Christie to return from a Grange meeting. As Christie approached with her sister Fannie, her mother and a friend, Almy emerged from the shadows.

Later, Fannie Warden explained the scene to a local newspaper.

“We were walking in the middle of the road and just as we got to the tree at the gate Almy stepped out into the moonlight. We all recognized him at once and as we did he said:

“‘You know me. I am Frank Almy. I have come 1,000 miles to see Christie and will see her alone. Now, Mrs. Warden you and the other girls go on and I won’t harm you, but I will see Christie.’

“With that he put his hand in the pocket of his coat and pulled out a big revolver, which shone brilliantly in the moonlight. At the same time he grasped Christie by the arm and endeavored to pull her away. Then I caught hold of her at the other side. It all took place in a much shorter space of time than it takes for me to tell it. As I caught Christie, Frank Almy leaned over in front of her and pointing the pistol in my face he hissed: ‘Fan, I hate you. You leave go of Christie or I’ll shoot you.’”

Fannie held on until Almy began to fire. Fleeing behind a bush, Fannie watched as Almy shot Christie twice, once in the head and once up her genitals, then left her lying beneath the willows.

Almy escaped before anyone could catch him. While a “wanted” poster circulated the region, Christie’s body was laid in the Dartmouth Cemetery, where she still remains today.

According to Ilana Grallert, processing specialist at Rauner Special Collections Library and Dartmouth Old Cemetery tour guide, the Christie Warden murder is one of few dark tales to haunt our campus cemetery.

Founded in 1771, the cemetery was primarily used for Dartmouth College staff and prominent Hanover residents. Grallert said that eight of the early College presidents are buried there, along with many trustees and professors.

“You also notice the same family names repeating: there’s a lot of Deweys, there’s a lot of Hitchcocks,” Grallert commented. “Because this was a very small town, people intermarried. Often a daughter of a professor married another professor. And what you also notice when you look at a lot of the early professor graves is they stayed here 35 years, 40 years; they basically stayed here till they died.”

Today, you cannot be buried in the cemetery unless your family owns a plot, and then only your ashes can be buried.

Grallert owes her fascination with the Dartmouth Cemetery to two important records, one written by W. W. Dewey in 1797-1859, and the other by Professor Arthur H. Chivers in the 1950s.

Chivers became interested in the cemetery as a Dartmouth freshman in 1898. Fifty years later, Chivers identified a need for a “card of index of all known burials in the cemetery,” so he gathered information from stone inscriptions, local genealogies and statistics, correspondences regarding the deceased, Dewey’s records from a century earlier, and other sources, ultimately compiling 1,814 entries.

“If you see the stones, a lot of that information is gone,” Grallet explained. “So if these two people hadn’t started to record some of this stuff, we would lose all this information.”

Without Chivers’ guide, I never would have found Christie Warden’s grave, marked by a low-lying stone near her family’s plot. According to sources who spoke with Almy the night he was captured, Almy visited this spot “as often as twice a week” after the murder, and he “expressed the deepest love for Christie.” Though he killed the girl, he also “loved” her enough to remain in Hanover after the crime, making his arrest inevitable.

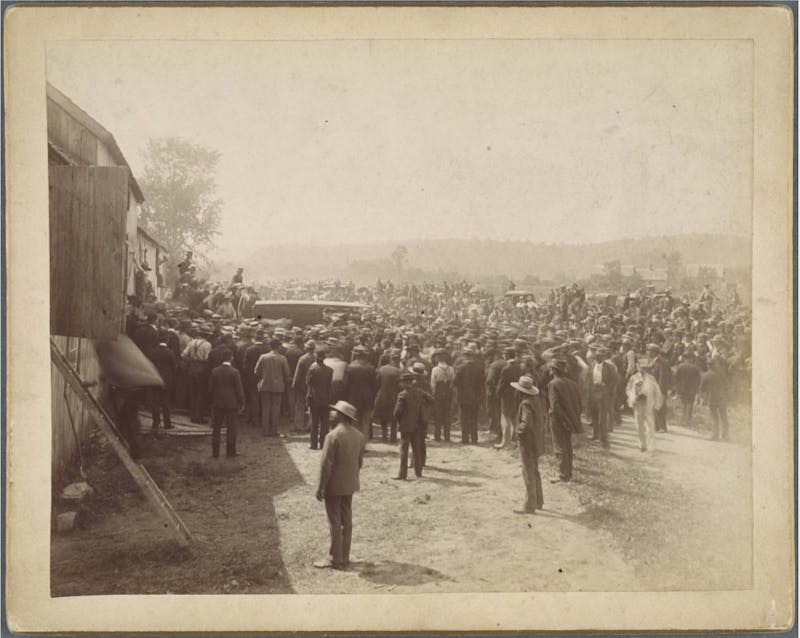

Weeks after the murder, Mrs. Warden found an empty jam jar under one of the Warden family barns, on what is now Reservoir Road. She notified the authorities, and watchmen soon witnessed Almy leave the same barn at 3 p.m.

The men tried to convince Almy to cooperate, but the murderer relented only hours later, bleeding from a gunshot to his leg. As Hanover lacked a secure prison at the time, authorities laid Almy in a room at the Hanover Inn. All night, people from the town and college, including children, circulated through the room, eager to “get a good view of the criminal.”

Frank Almy lay wounded in the Hanover Inn after his capture.

Before long, investigators revealed that Frank Almy was actually George Abbott, an escaped convict from a Vermont state penitentiary. As the New Hampshire Sunday Telegram reported, “This is the secret which he confided to the murdered girl. It was to reclaim him from evil that she was kind to him. It was because she could never link her life with a convict that he killed her.”

News of the tragedy spread around the country, reported in The New York Times and, later, in compilations of famous murder stories. Meanwhile, Almy was tried, found guilty and hanged.

Today, Christie lies peacefully in the Dartmouth Cemetery, less than a stone’s throw from Tuck Mall. Dartmouth students pass by her every day, but few think twice about the cemetery, let alone the fascinating history beneath the graves.