The preferential treatment of legacy students in the admission process at many American universities is a practice that has been around for almost a century despite the practice’s anti-Semitic and xenophobic roots. In fact, the practice of legacy admissions began at Dartmouth in 1922, and soon after, other institutions adopted the practice as a means of reducing the number of recent Eastern European immigrants — a large majority of whom were Jewish — who were admitted. Today, universities maintain the practice more out of tradition and fear that without it, alumni donations will plummet, but its effect is no less damaging than it was at its bigoted beginnings. In honor of the 100th anniversary of Dartmouth’s use of legacy preference in admissions, Dartmouth should acknowledge the ridiculousness and inequity of this practice and end the use of legacy preference in admissions.

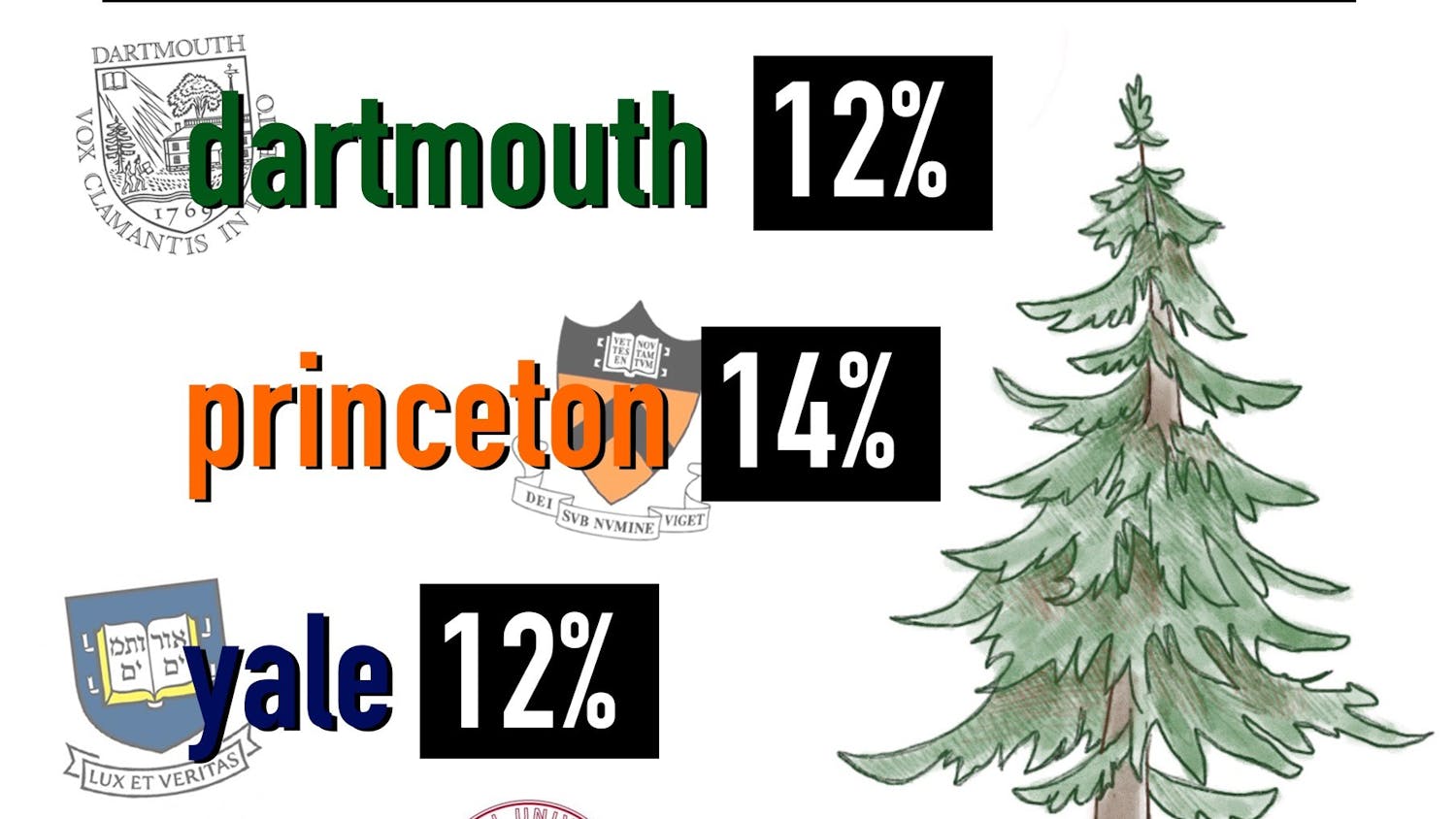

Like at most elite universities, a large portion of the student body at Dartmouth comes from affluent families. In the Class of 2013, for example, 69% of Dartmouth students came from families in the top 20% of the income distribution, while a meager 2.6% came from families at the bottom 20% of the income distribution. Today, legacy preference continues to afford mostly white, affluent students — students who are already at a significant advantage in terms of college admissions thanks to better access to college prep resources, competitive private high schools, elite sports and generational knowledge — an even greater leg up. The extent of this advantage is clear in the numbers: A Harvard University study that examined admissions at the University of Pennsylvania, Princeton University and Harvard showed that legacy students are almost four times more likely to be admitted to prestigious universities relative to non-legacy applicants. At Harvard, a National Bureau of Economic Research study showed that 43% of white students are athletes, legacies, children of faculty or staff or children of donors; the figure for Black, Hispanic, and Asian American students was just 16%.

This discrepancy is troubling not simply because it shows a clear bias that universities have in favor of wealthy, white, legacy students, but also because it clearly illustrates why low-income students are so poorly represented at elite universities. White, wealthy, legacy students already have every factor in their favor during the college admissions process, and the fact that colleges feel the need to give them yet another hand up simply due to their pedigree further compounds the inequity.

Not only do low-income students not have access to the same resources or high schools as affluent students, but they also have responsibilities that affluent students may not, such as having to take care of their siblings while their parents are at work or having to hold down a job during high school that may limit how much time they can devote to academics and extracurricular activities. Moreover, low-income students, unlike affluent students, are more often the first in their families to attend college, meaning that even applying to college can be a challenge for these students who are unfamiliar with the process and cannot simply turn to their parents for advice. In short, not only does legacy preference compound the advantages of the well-off; it also compounds the disadvantage experienced by low-income students.

Harvard University’s Dean of the College Rakesh Khurana has suggested that legacy preference fosters diversity by placing students with experience with the college alongside those without it. This is plainly absurd: legacy preference is not needed to foster this type of ‘diversity.’ Legacy students already tend to be in the most desirable applicant pool — the added preference is simply the stamp on legacy student’s acceptance letters. Moreover, if college administrators have concerns about diversity in regards to legacy admissions, it should be in regards to the way the practice reinforces socioeconomic inequality. The practice provides an additional advantage to a group of individuals that is for the most part already socioeconomically extremely privileged and overrepresented on elite college campuses.

Other proponents of legacy admissions argue that doing away with legacy preference will cause donations from alums to plummet and, in turn, reduce institutions’ capacity to help lower income students. However, this argument fails to acknowledge the fact that at institutions that have already done away with legacy admissions, there has not been any significant change in donations. A 2010 study of seven institutions that did away with legacy preference reported that none of the seven institutions studied saw any significant changes in alumni giving and concluded that there was not a statistically significant link between legacy preference and alumni donations. In this sense, if colleges choose to reduce the financial support given to lower income students following changes in their use of legacy preference, this decision would not be due to a decrease in donations, but rather to other, unrelated factors.

Ultimately, legacy admissions are not a tradition worth maintaining. While Dartmouth is certainly not the only college that still considers legacy status in admissions, it was the first, and that gives it a unique opportunity to right its wrongs. Legacy preference does little beyond perpetuating socioeconomic inequalities by providing already privileged students with an even greater advantage during the college admissions process. If the College is committed to “build[ing] a diverse community of students,” as stated in their values, they should put their money where their mouth is. The most appropriate way to celebrate the centennial of the invention of legacy preference is with its abolition.