Last week, a letter titled “A Letter on Justice and Open Debate” was published in Harper’s Magazine. The letter was undersigned by 153 scholars, writers and political theorists, including Dartmouth’s Eli Black professor of Jewish Studies Susannah Heschel. J.K Rowling, Noam Chomsky and Margaret Atwood were among the signers of the letter, which warns against a perceived growing societal trend in public shaming and ostracism for holding opposing views. The Dartmouth sat down with Heschel this week to discuss her views on ideological conformity and the importance of open discourse.

Why did you decide to sign onto this letter? What do you think is the importance of open debate and why is it important that this letter was written?

SH: The most important purpose of being a scholar is to engage in open debate — the word "open" shouldn't even be necessary — and I have in fact engaged in debate with other scholars over a variety of different kinds of issues. We debate how to interpret a particular document or which sources are most relevant, or the influence of an idea in its time and subsequently. I debate not because I necessarily want to win — very often I want to be convinced, I want to change my mind because I want to think more deeply and more creatively. So, it helps me to talk to people who disagree with me. In fact, I do change my mind. I had a disagreement with a colleague some years ago about a particular article that we both read, and since then I've decided that she's right. I disagreed at the time, but it helped me to have her interpretation in my mind. Over the course of several years, I've thought about it from time to time, and I now think differently about the article that we debated. Of course there are times when I don't agree, by the way, but I really appreciate that.

The letter warns against the potential of the current movement for social justice to turn into "intellectual dogma," but it also refuses any false choice between justice and freedom. How do you weigh the importance of what the current movement is fighting for against the dangers of ideological conformity?

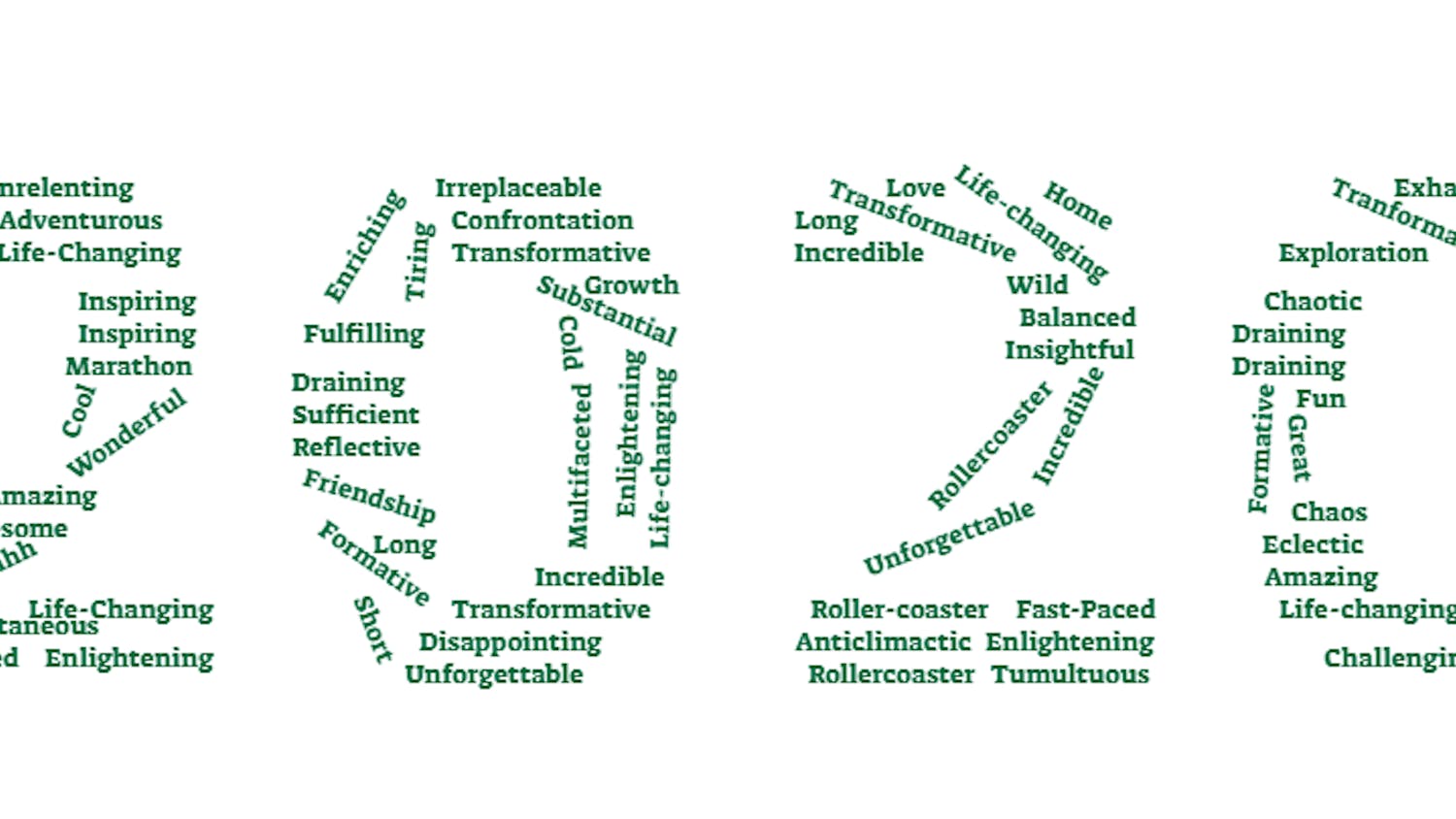

SH: I think that of 153 people who signed the letter, each one will give you a different reason and probably point to different passages in the letter, and say, this is what caught my eye, this is why I signed it. So I can tell you what caught my eye. First of all, I'm very concerned about Donald Trump. I think he is a corrupt president who is undermining our society and causing terrible calamity in our medical health with this terrible virus. He's just been a terrible, terrible president in every way. And so, the first paragraph, which mentions Trump as an ally to the "forces of illiberalism," that's what caught my eye. Yes, he's promoting illiberalism, and this was from the very beginning when he made comments that were racist and mocking people with disabilities. There are plenty of examples.

Now in the next paragraph, what caught my eye was the public shaming and ostracism. I've written quite a bit about Nazi Germany and people there who supported Hitler, and I'm interested in what they said and why they supported what they heard from Hitler. My interest is in understanding their rhetoric, their publications and their speeches. I'm not interested in whether or not the person was an anti-Semite, whether the person was a fascist and then understood their identity as such. I'm interested in what they say and what they do, and that's most important. I don't like the labeling. If someone said something anti-Semetic, I want to talk about what they said and not about who they are. I think the same should be true in our debates.

I also know that people make mistakes. I've made mistakes as a mother, as a teacher, as a scholar — there's an error in a footnote from 20 years ago that still bothers me, and so forth. So the letter talks about the seriousness, the public shaming, the ostracism, the moral certainty and I find that among the responses, the negative responses to the letter that have come out assume that the letter is attacking this person, that institution, this journal. Why make those assumptions? My feeling about the letter was that it takes a neutral stance. It says it doesn't matter if it's coming from the right or the left, this kind of ostracism is unacceptable. We can disagree, but you don't ostracize people, or shame people. We should listen and explain why you disagree and talk about it and debate it and be open to the possibility that maybe the other person is right and you're wrong. You may change your mind. What are people afraid of?

How do you think that movement leaders could better incorporate diverse viewpoints while still working to advance their cause?

SH: I think we have too many lines, and we say, "must not cross this line." I'll give you an example. I brought a visiting professor from Israel, to teach for a term, and while he was teaching in Hanover, I read something in the newspaper that talked about some groups that were very, very anti-Israel and really hostile, saying “Israel shouldn't exist” and so on. I said, this is horrible, one shouldn't talk to such people. My colleague said to me, actually, those are precisely the people we should talk to. What's the point of talking to people who agree with us? Let's talk, it's much more important to talk to people we disagree with — hear them out, listen to them, maybe convince them.

A lot of people these days seem to me, and I would say this is true in the Jewish community too, if you don't agree, if you cross this line, I won't speak to you. You're ostracized, kicked out of the Jewish community, basically, if you say such a thing. And this comes up a lot, I know someone right now who made a really innocent comment that was misinterpreted by some ignorant people who are threatening him and want him to be fired. That's not right. So that's why I signed this letter. There are going to be people, I would say for students, there are going to be professors who have views about the world that are very different from yours and from your parents and your upbringing. But those people should not be fired from the College because you disagree and think their views are terrible, we should go and listen to them, argue, convince them, or be convinced or simply agree to disagree. But the more you can hear a variety of viewpoints, the richer your mind will become, and the better you'll understand yourself and your own arguments and be able to defend them. I find it very disturbing when people think they're being political by talking to other people who agree with them. That's not politics. To be political is to talk to people you disagree with.

The letter also condemns the idea of “cancel culture” when someone holds a somewhat different view from the accepted norm. Is there a better way for society to handle people whose viewpoints are inherently intolerant or hateful?

SH: In response to this Harper's letter, somebody at another university wrote to me, saying, "I will never assign or cite any of the works of any of the people who signed this letter." Now, the letter doesn't use the term "cancel culture," but I suppose that would be an example of it. I think that's ridiculous, but also very dangerous and highly unprofessional. I will not deprive my students of the work of important thinkers of the past or the present because I don't like their politics. If I don't like the politics and that's relevant to the assignment we'll talk about it in class, but I will certainly go on teaching, for example, some passages from “Mein Kampf,” Hitler's book. Obviously if I write about Nazis it doesn't make me a Nazi, but I don't believe that one should ever censor in scholarship in that way. In the same way, I would say, would I vote on a tenure case based on my political views, and differences with the person? Absolutely not. That's completely unprofessional.

It sounds like as long as there is earnest discussion where both parties are invested in the process of debating rather than acting on a knee-jerk cancellation reaction, disagreement on some issues can be acceptable.

SH: I think we also have to put things in context. I mean, I hold somebody much more responsible today for saying something racist than I do somebody in the Middle Ages. It's still bad and wrong and I point out and criticize it, but I think, "For heaven's sake, today you're talking like this? That's awful." So it also depends. It's not that I would cancel, but I would criticize more heavily and be much more disturbed.

I know people who have lost their jobs for their politics and I think that's terrible. I also know that . . . some speakers come and students will demonstrate or try to disrupt. I don't think that's appropriate. I think if you don't like what someone is going to be saying, either don't attend or write a column in the student newspaper, and talk to your friends about it. You could even hold a sign outside the building that says “I don't agree,” but I don't believe ever that you disrupt.

Lauren ('23) is news executive editor for The Dartmouth. She is from Bethesda, Maryland, and plans to major in government and minor in public policy.