At Dartmouth, we’re steeped in tradition. Whether it’s through big things like attending First-Year Trips or circling the Homecoming bonfire, or small ones like hearing the bells of Baker Tower play the alma mater every day at 6 p.m., we are constantly reminded that we are part of a larger community as we engage with the many rituals that foster commonality among our diverse experiences. As a community, we are well aware of this; we speak of tradition as one of Dartmouth’s major values, and we tend to refer to our many traditions with affection, excitement and pride.

In fact, our traditions are so prevalent that we sometimes joke that Dartmouth is a religion. Yet despite religion being in some ways the ultimate tradition, our engagement with the topic typically ends here; religion tends not to come to mind when we talk about tradition at Dartmouth. To address this aspect of tradition, I spoke to religion professor Timothy Baker about his work.

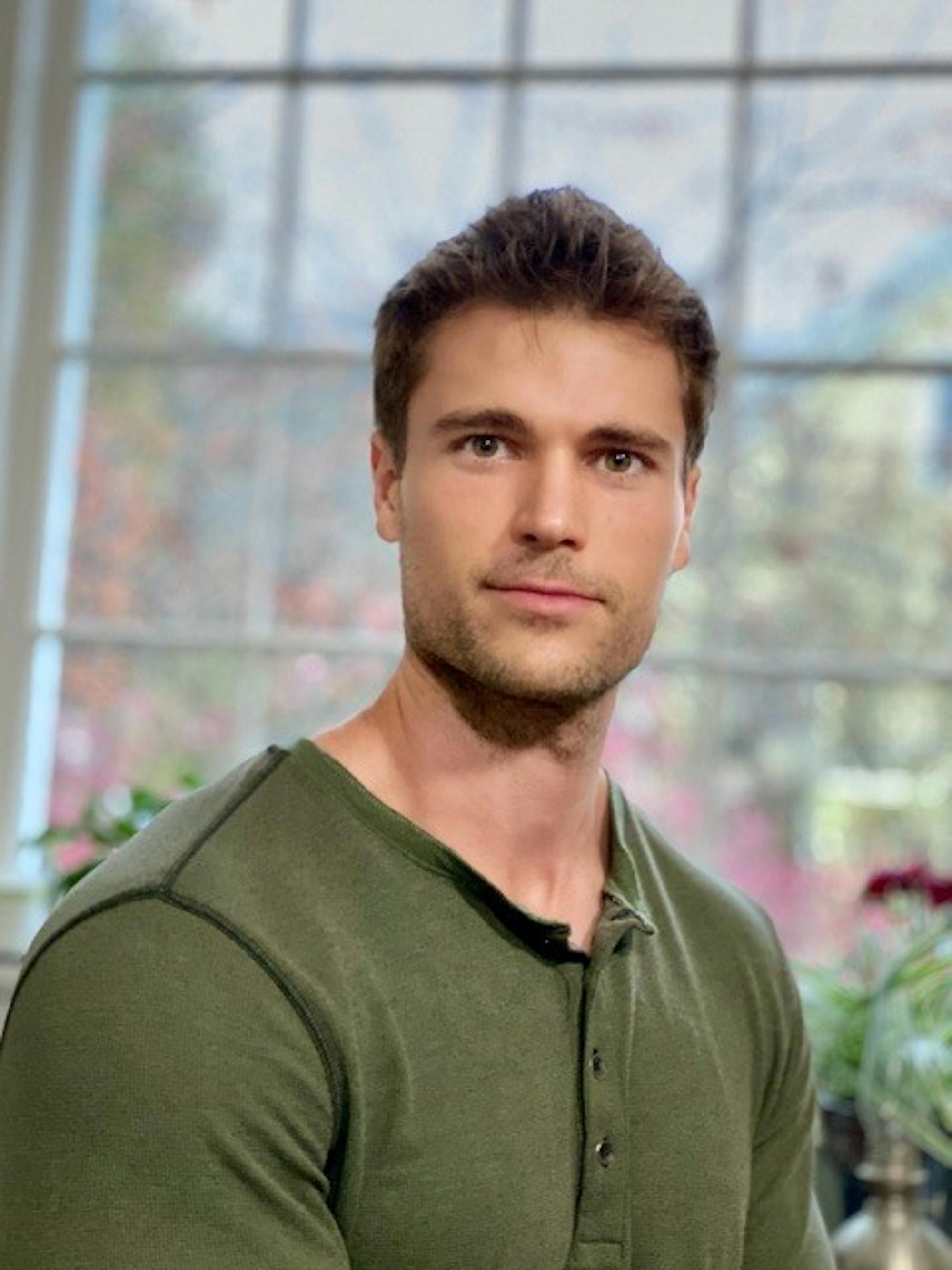

Baker teaches in the religion department and also serves as Assistant Dean of the Faculty and faculty advisor for the Humanities Living and Learning Community. His studies include work on late antique and medieval religious history and manuscript traditions, though he also conducts research on practices of becoming more like God, sacred spaces, and ideas of connection and compassion among members of a community.

Can you talk a little bit about what you’re currently researching and why it interests you?

TB: I’m interested in all sorts of things. I’m kind of naturally curious, but I’m particularly interested right now in three main topics. One is how people seek to become like God, whatever that means, broadly construed. So, ideas of ascension or apotheosis or transformation or transfiguration. I’m interested in that space of becoming great or trying to become greater than oneself. I’m also interested in the way in which people negotiate space and whether that’s a physical space, like a church or a monastery, or an imagined space, kind of thinking of oneself as a temple to God or thinking of the community as a church of living stones. I’m interested in the way in which sacred spaces are constructed and maintained, and the boundaries between the sacred and the profane.

I’m particularly interested in ideas of connection and compassion among members of a community. How monastic brothers relate to each other and to their work, and to their community, or how lay brethren relate to the priesthood or how Jewish communities relate to Christian communities — whether they do or do not — and what the limits of that kind of negotiation may be in the Middle Ages. Also, how human beings relate to God and how they think about their connection to the divine and how they embody that connection or maintain that connection. And that idea of connection — and in the classical sense, that idea of compassion — of suffering with someone else, of connecting to someone by suffering with them or engaging with them in that degree of shared common divinity and humanity really interests me both in the Middle Ages, which is where I spend most of my time, in monastic communities and Jewish communities in the Middle Ages, but also just generally speaking as we think about what compassion looks like in practice, what it looks like biochemically, what it looks like in the historical record, in records of narrative tales, poetry, art, music, and also just how we think about that throughout time.

The idea of becoming like God sounds fascinating, but also counterintuitive. Can you unpack that a little bit more?

TB: To me it’s one of those particularly fascinating things, this idea of ascending into God, because it has different kinds of resonances and different kinds of meanings over time. There can be this way of thinking about the relationship between heaven and earth as starkly divided, that God kind of sits upstairs on his throne and that we sit down here and that God doesn’t bother us and we don’t bother God and we have no connection whatsoever. The medieval mindset, which is coming out of a classical mindset, doesn’t really think of that boundary as being so distinct. Most people know about medieval people thinking about things like fairies and sprites and gnomes and elves and things like that, and all that notwithstanding, the idea really is that there is a fairly thin veil between our world and the world of the dead or our world and the world of these kinds of supernatural beings, whether they be local beings like sprites or supernatural beings like divinities, or like God, if we’re talking about a purely Christian context. There is this thinness. Then, the question becomes, what do we do with this thinness, and what is the whole point of being a religious person or doing anything?

For the most part, if I’m, you know, a standard lay person, a standard peasant, I’m probably just interested in if I am going to be okay and is the Lord going to be taking care of me — Lord here both in the sense of the feudal Lord and in the sense of the divine Lord that I’m thinking of as a kind of feudal Lord — that I give stuff to him and he protects me kind of thing. In that sense, it’s like, okay, I’ll do my thing, I’ll go to church, I’ll be part of the community. The priest will take care of me. The priest will act as the person who’s praying and interceding on my behalf. And then I can work the land and the knights can go out and fight. And while they’re fighting and I’m working, the priests are praying on behalf of both of us and that’s good enough.

But you also have this subset of the population, particularly within the contemplative orders and the monastic orders that want more out of that experience. They then take on more of a philosophical mindset and they’re thinking, what does it mean to be a religious person or to be created in the image of God or to move toward that kind of space? And they started talking in terms of becoming God, or becoming like God, which just struck me as being really fascinating, and I want to know more about what does it mean when a monk says that okay, you do this, you do X and Y and Z and you become God. That seems terribly unusual for a Christian to say. And it turns out that it’s not, but it comes with a certain kind of caveat, or potentially for our purposes, a drawback or something like that. Which is to say that when these monks think about becoming like God, they think about it as becoming so much like Jesus vis-à-vis a particular reading of Paul, that they lose their distinction and their individuality as Tim or Arianna, and they become God. Which is to say that insofar as one gives oneself totally to the Godhead, one becomes God. In that sense, you are God, but you are also no longer you in the sense that all the kinds of particularities that make you tick, that make you think about things and do things and act in certain ways that are mediated by your own desires, are now washed away. Because by becoming God, you desire what God desires. And you act like God acts.

One way that people often construe religion is through the lens of tradition and ritual. How do you think those concepts play a role in religion?

TB: So, there are certain kinds of rituals and everyone knows the different kinds of things that one does. There are various specific rituals: weddings and funerals and confirmations and Eucharistic celebrations and masses and things. Those are all particular kinds of rituals of particular kinds of groups. But I’m really interested in, or I’d like to have my students think more about, what those rituals negotiate in terms of agency — personal agency, communal agency and interpersonal agency. What do we have as our expectations for ourselves? What do we have as our expectations for each other? What do we have as our expectation for the community as a whole? Because I think these translate into what it is that we’re thinking, or what they’re thinking, or our monks are thinking, or our nuns are thinking when they’re trying to perform their ritual in terms of what are they doing, and why is that important, and why is that valuable to them? And why did they construct it that way? And why do they say what they say and do what they do and create a tradition when they create a tradition and locate a tradition that they’ve just created as part of a longstanding tradition that’s not actually true, but that they created? Why is it so important to create narratives and to structure narratives that way? And I think that we can think about that in terms of what they might’ve been thinking or what they might’ve been doing based on what it is that we see.

This article has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.