At this point, it’s no secret that the eighth and final season of “Game of Thrones” was extremely polarizing. The mileage of fans and critics varied, but the general consensus seems to be that the final three episodes torched what has quite possibly become the most popular TV series of all time. Showrunners David Benioff ’92 and D.B. Weiss resolved the show’s two major plot threads by essentially splitting these last six episodes into two mini-seasons; whereas episodes one through three feature the long-awaited confrontation with the White Walkers, episodes four through six cover the subsequent power struggle over the Iron Throne, the seat of power in the story’s fictional Seven Kingdoms. While the first arc was generally well received, it’s the baffling storytelling in the second that will haunt “Game of Thrones” forever.

All of these flaws ultimately revolve around the singular decision to turn Daenerys Targaryen — a feminist icon and probably the show’s most popular character — into a villain. To illustrate, perhaps the season’s most tone-deaf moment of sexism and racism arrived when Missandei, the show’s only prominent woman of color, was brutally executed in chains simply to spur on Daenerys’s character arc. Not only are the optics of a woman of color getting murdered for the sake of a white woman’s character arc stunningly ill-conceived, but it’s made worse by the fact that the character arc in question is so atrocious.

For the uninitiated, Daenerys Targaryen is one of the last surviving members of the Seven Kingdom’s original dynasty. We first meet her as a 16-year-old girl living in exile, her father having been deposed around the time of her birth. In a bid to reclaim their crown, her brother sells her to a warlord. After both men die, Daenerys rises from the ashes with three baby dragons and proceeds to conquer three cities in a region called Slaver’s Bay, liberating the eponymous slaves. After some turmoil, she finally sails for the Seven Kingdoms, only to divert her attention to help Northern leader Jon Snow defeat the aforementioned White Walkers. Just as she is poised to win back her family’s throne, Daenerys starts following the footsteps of her insane father, massacring innocent millions when she sieges the Kingdoms’ capital. She becomes queen for five minutes … until Jon stabs her.

Before I address why this story arc has such pernicious implications, we need to briefly address some popular criticisms of Daenerys. Recently, a small but vocal minority of fans have posited that the showrunners’ poor treatment of Daenerys is justified due to the air of white saviorism that pervades discourse about her, particularly in relation to the Slaver’s Bay subplot.

Is this a fair assessment? This topic could take up an entire book, but suffice it to say – yes and no. Daenerys’s arc during the middle of the series is often about deconstructing the savior trope; she must learn that her good intentions are no substitute for consulting and empowering the oppressed people she seeks to uplift. At the same time, the reader’s awareness of Daenerys’s inner thoughts ensures that she is always framed in terms of her compassion. Although the show has struggled recently to balance the same tightrope walk that the books manage masterfully – for example, George R.R. Martin, whose "A Song of Ice and Fire" book series served as the inspiration for "Game of Thrones, makes it clear that slavery in Slaver’s Bay is not racially based, whereas it is in the show, further adding fuel to white savior imagery — the through line is still the same. This is why, despite what same fans have argued, Daenerys’s occasional viciousness in previous seasons doesn’t effectively foreshadow her descent into villainy. The narrative and framing in both the books and the show have ultimately been about an extremely flawed young woman with a ruthless streak who is defined by an overriding sense of compassion that always wins out.

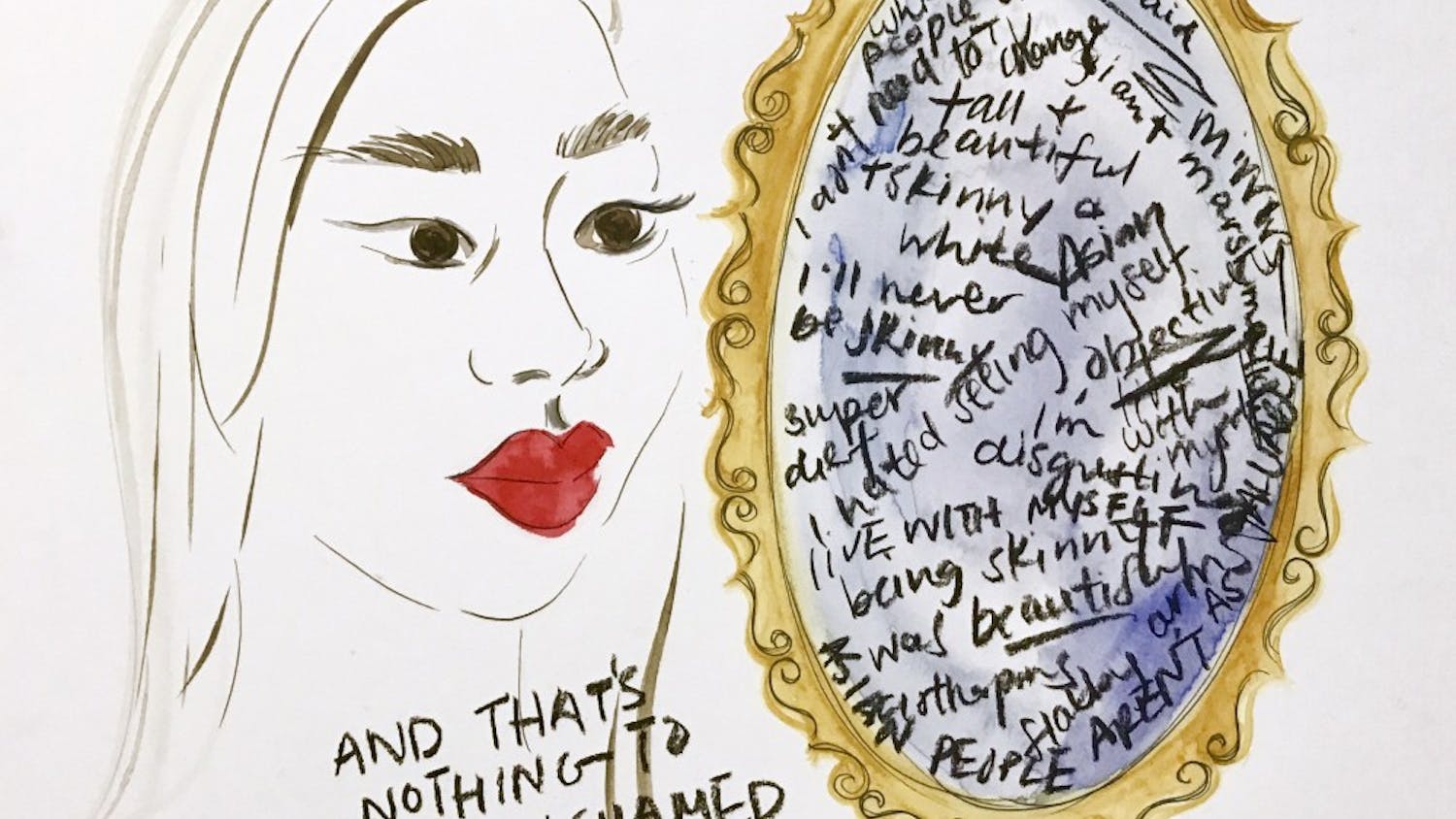

In short, we should absolutely parse the problematic elements of Daenerys’s storyline in the books and especially in the show. And if you don’t like her as a character, that’s fine. But marshalling half-baked, bad-faith criticisms as a means of shaming everyone who felt empowered by her isn’t productive. No one was wrong to see Daenerys as a feminist icon or to feel inspired by her fight against the patriarchy. This is precisely why her transformation in the final three episodes is so insulting.

I think it’s fair to assess that some version of this ending is what Martin has planned for the last two as-of-yet-unpublished books in the series. Yet I have far more faith in his ability as a writer, and I also don’t think Daenerys’s final arc needed to be so inherently misogynist. I could see Martin using his narration to give the reader insight on her devolution; in a sense, the natural culmination of her compassion would be to liberate the entire world from tyranny, risking becoming a tyrant herself. Not only would this retain a necessary sense of ambiguity surrounding her death, but it would more effectively complete Martin’s deconstruction of the savior trope. And the show’s version of Daenerys’s death almost portrays this, highlighting how her tyrannical tendencies are undergirded by the precise humanitarian impulses that make her endearing. But then the scene ruins itself by emphasizing Jon Snow’s anguish/man-pain at betraying the woman he loves upon killing her, thereby framing the toxic mindset that defines domestic abusers in a sympathetic and even heroic light.

Moreover, all the potential in the beginning of that scene is undone by its context. Rather than carefully documenting how Daenerys’s increasingly dire circumstances might cause her to mistake liberation with tyranny, Benioff and Weiss decided that “Daenerys goes crazy” needed to be a plot twist instead of character development. Thus, in a bid to make her metamorphosis convincing, the filmmakers rely on the worst kind of visual short hand possible. In episode five — during which Daenerys slaughters millions in the capital — director Miguel Sapochnick never uses a close-up on Daenerys prior to the siege that isn’t mediated through the perspective of another character. The only proper close-up we get of her — the only moment that purely belongs to her — occurs right before she makes her fateful, genocidal decision, emphasizing her sense of emotional turmoil. And actress Emilia Clarke may sell the hell out of it, but the visual language here explicitly indicates that Daenerys’s emotional instability is the cause of this tragedy, thereby playing into one of the worst misogynist clichés about how women are too emotional to be leaders.

Moreover, “Game of Thrones” doesn’t just fail Daenerys as a character but also torpedoes her entire worldview in the process. As I’ve alluded to, Daenerys humanitarian policies made her the most politically revolutionary leader within the context of the show’s diegesis. Her talk of “breaking the wheel” that crushes the Kingdoms’ common folk made her the closest this story was going to get to a Marxism-inclined monarch. Likewise, this philosophy fits neatly with Martin’s internal critique of the fictional culture of “A Song of Ice and Fire,” openly acknowledging that this culture is in desperate need of change.

In the wake of the final season, Clarke has admitted that she was never fully on board with the direction her character took. Like many fans, Clarke drew strength over the years from her own character (during a time when she had two brain aneurysms, no less). Although her performance has recently been lauded, Clarke’s acting abilities were largely maligned for the first few seasons. Personally, I think she’s always been stellar; Daenerys is a hard character to bring to life because she’s both a naïve adolescent girl and also the literal “Mother of Dragons.” I give kudos to Clarke for ensuring that Daenerys always sustained the spectator’s emotional empathy, even while imbuing her with an otherworldly, deity-like aura. Regardless, it’s safe to say that Emilia Clarke deserved better.

In fact, everyone deserved better from this final season. Those who wanted the last few episodes to commit to a proper deconstruction of the savior trope (as I imagine may happen in the books) deserved better writing. Those who felt empowered by Daenerys deserved not to be told that they’re too emotional to aspire to leadership. And above all else, those of us who believe that a better world may be possible, that the “wheel” of oppression need not be interminable and that female leadership may be key to making some progress, deserved better than to be told that we ought to be satisfied with a status quo built on tenuous, systemic complacency.