When the typical Dartmouth student thinks about the importance of athleticism in Dartmouth’s history, they may focus on annual traditions such as running around the Homecoming bonfire, diving into Occom Pond for the Polar Bear Plunge or hiking The Fifty. But Dartmouth sports also have a storied history of success as well, as the Big Green has produced professional athletes since the late 19th century.

Many of the College’s athletes in other sports have gone on to pursue professional careers both as players and coaches. Dartmouth has had a robust history of producing professional athletes for a long time particularly in “Big Four” men’s leagues: the National Basketball Association, The National Football League, The National Hockey League and Major League Baseball.

Dartmouth had a stronger presence in Big Four professional sports in the first half of the 20th century, with a brief dip during the 1930s Great Depression era. Recently, the number of professional Big Four athletes increased in the 1990s and the 2000s. Dartmouth has been on the rise in the National Hockey League recently, while the number of National Football League players who bleed Dartmouth green has decreased.

The Ivy League is often dismissed as an athletic powerhouse, but Dartmouth baseball players have certain advantages when being scouted by teams.

“Progressive scouts understand that the discipline required to handle this academic curriculum, practic[ing] at night time and in the cold, and still be pretty good – those players are interesting,” head coach Bob Whalen said.

Still, from an MLB-organizational perspective, the value of a Dartmouth degree can actually be a net negative.

“There’s this stigma on the downside that you don’t take [Dartmouth players] unless they’re high-profile kids because they have better options,” Whalen said. “When you’re a major league organization and you’re putting a minor league system together, you want a whole bunch of guys with no options. They’ll stay there and play as long as you’re willing to let them show up to the park everyday.”

Nonetheless, Dartmouth alumni have had a history of success in major league baseball, with a high number of players in the MLB at the turn of the 20th century and an impressive array of quality players since then.

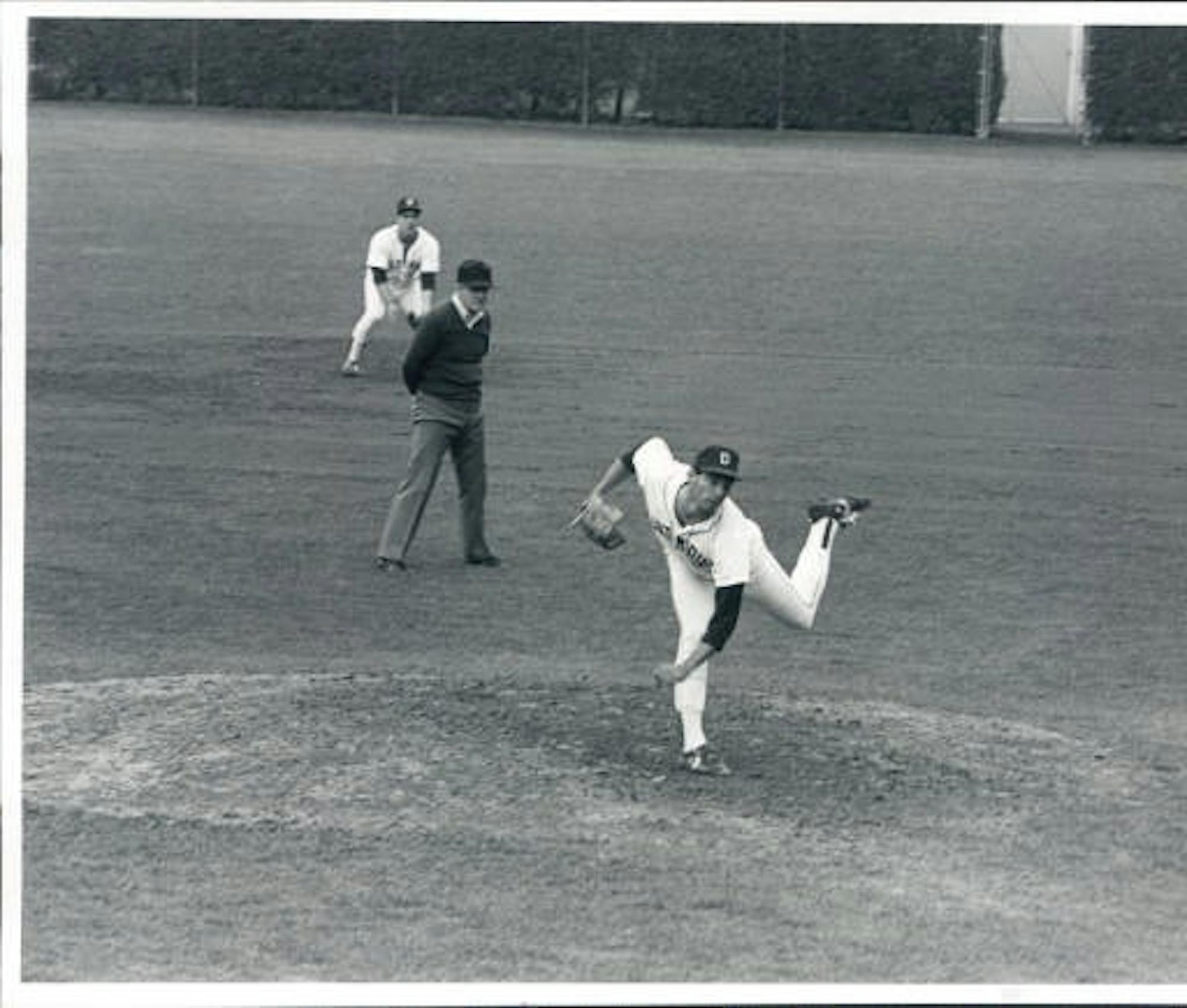

Among them was Robert “Red” Rolfe ’31, whose four All-Star game appearances with the New York Yankees earned him the namesake for Dartmouth’s baseball stadium. Additionally, Jim Beattie ’76 was a consistent Mariners starting pitcher, while Mike Remlinger ’88 and Brad Ausmus ’91 enjoyed especially successful, long-lived careers in the 1990s and 2000s. Currently, Kyle Hendricks ’12 stars as a frontline starting pitcher for the 2016 World Series Champion Chicago Cubs. Ausmus later worked as the manager of the Detroit Tigers and is currently a special assistant to the general manager of the Los Angeles Angels.

“Thankfully, our program has done well enough on the field and in developing players that guys are like, ‘Hey we need to make sure we see Dartmouth,’” Whalen said.

While Dartmouth has played a role in these players’ trajectories, Whalen was careful to note that they were fast-tracked to begin with.

“It’s fun to coach guys like that, but you don’t take any credit for it,” Whalen said. “You don’t take kids without talent and have them get to the Big Leagues.”

Dartmouth can be particularly helpful in cultivating professional prospects’ mental skills.

“You coach a lot of kids that do have talent that don’t understand the profession and that there’s a business side to it, and they need to understand what it takes to play at the highest level,” Whalen said.

With select individuals having made the transition to the MLB after Dartmouth and a host of other players in the minor leagues awaiting their chance, Whalen makes sure to keep his professional athletes in communication with the school.

“We want them to know that we’re proud of them, that we’re invested in their development and that they made great impacts here.”

The Big Green has produced NFL players since the league’s inception in 1920, and the program has remained committed to providing opportunities for its student-athletes.

“My thought is to put guys in a position that if they want to pursue a dream in athletics, football specifically, they have the chance to develop their skill set here without compromising their desire to be a doctor, professor, banker, engineer [or] faculty member,” head football coach Buddy Teevens ’79 said. “If it doesn’t work out, these guys have livelihoods available to them and career options outside of football, but they love the game, and we try to develop them to their fullest abilities athletically.”

When pitching a player to an NFL franchise, Teevens is honest about where his players can contribute as a player, student of the game and teammate.

“We say, ‘Hey, here’s what he can do well, here’s areas of improvement, here’s what his attitude and his work ethic is, he would like an opportunity to play professionally,’” Teevens said. “‘He’s a guy that’s probably going to learn your offense or defense before any of your guys, he’s never going to cause you trouble off the field, he takes care of his business,’ and they make their decision,”

Similar to Whalen, Teevens singled out academic excellence as a compelling advantage his players have when showcasing their abilities.

“I was pleasantly surprised when I came back after I was at Stanford [University], [the University of] Florida and [the University of] Illinois at the size, the speed, the athleticism. We can do more offensively and defensively in a lot of places because of the intelligence of our players,” Teevens said.

With videotapes and players’ physical fitness data available, football has been increasingly open to players from all schools.

“Nowadays it doesn’t matter where you play; it’s what you do when you play there,”said Duane Brooks, pro-liaison and assistant coach for Dartmouth football. “If you have the body type, the NFL is all about what you look like first. If you look the part, they think at some point if you can run the speeds you’re supposed to run, you’re going to have a chance.”

Despite strong recruitment points that Brooks and Teevens have to offer, football has not produced nearly as many NFL players as in the early 1900s, though many get signed and invited to NFL training camp. Regardless of the odds, Dartmouth football makes the effort to give players a chance at the NFL if that is their goal.

“Statistically, less than two percent of guys who play college football have a chance to play professional football at any school,” Teevans said. “For the Ivy League in particular, the number is not wonderful, but it’s like the lottery: if you don’t buy a ticket you don’t have a chance to win anything.”

Indeed, Dartmouth has won the lottery with some of their players, starting with NFL Hall-of-Fame lineman Ed Healey of the Class of 1918 all the way through to quarterback Jack Heneghan ’18 and safety Colin Boit ’18, who are vying for NFL roster spots 100 years later.

In the late 70s and early 80s, Dartmouth produced exceptional talents, including All-Pro linebacker Reggie Williams ’76, who was the NFL Man of the Year in 1986; Nick Lowery ’78, who at one point held the record for most career field goals, journeyman quarterback Jeff Kemp ’81; and former Cincinnati Bengals head coach Dave Shula ’81, who now acts as a wide receiver coach at Dartmouth.

“He’s at the pinnacle of success, he’s [been] an NFL head coach — there’s not a lot of those guys around,” Teevens said of Shula. “He was the athlete that worked extremely hard at it — he did a wonderful job in the classroom, and interpersonal skills [made] him one the most popular guys that came from his class.”

Dartmouth’s most prolific NFL talent, according to Teevens, was 1992 Ivy League player-of-the-year Jay Fiedler ’94, who threw for 66 touchdowns and 11,040 yards over five seasons for the Miami Dolphins, setting a 36-23 record as a starter.

Overall, Dartmouth football has developed many formidable NFL talents, embodying Teevens’ goal for athletes who aim to continue their football careers. “I want a great football player at football time, a great student at academic time and a great guy all the time,” Teevens said.

Men’s basketball has been nearly unsuccessful in producing NBA athletes since the end of the 1950s, with only Walter Palmer ’90 and James Blackwell ’91 playing in the NBA. Though the Big Green had highly successful seasons with Bryan Randall ’88 and Jim Barton ’89 as captains, both of whom played professionally after graduation, neither played in the NBA itself.

The Big Green’s best professional talents were Dick McGuire ’44 and Rudy LaRusso ’59. McGuire led the Big Green to the NCAA championship game in 1944 before earning five All-Star appearances and a Hall-of-Fame spot for his time with the New York Knicks and Detroit Pistons. LaRusso, nicknamed “The Ivy Leaguer with Muscles,”garnered five All-Star appearances between the Lakers and Warriors while averaging 15.6 points per game in his career.

Besides 1929 Stanley Cup winner Myles Lane ’28 and Edward Jeremiah ’30, Dartmouth did not supply any NHL players until Carey Wilson ‘83, who had 169 goals and 258 assists over his career.

The College hockey team took off at the start of the 21st century, graduating a remarkably high eight NHL players over the first decade. Among these were Lee Stempniak ’05, who has scored 203 times with 266 assists for teams across the U.S. and Canada, and Ben Lovejoy ’06, who was the first New Hampshire native ever to win a Stanley Cup when he did so with the Pittsburgh Penguins in the 2015-2016 championship.

Among the MLB, NFL, NBA and NHL, Dartmouth alumni have made significant impacts on the Big Four professional sports. All four sports have produced stars — from Ed Healey to Kyle Hendricks — proving Dartmouth can develop players just as Division-I powerhouses can.

With current technology, players from all over the country, including Dartmouth, have a shot at success in professional sports.