While many students in Hanover may feel far removed from the current immigration debate occurring across America, seeing only an occasional social media post or a sporadic snippet from CNN in King Arthur Flour, for Valentina Garcia-Gonzalez ’19, these Senate floor speeches and presidential tweets carry significant weight.

Like a number of other students at Dartmouth and approximately 800,000 other Americans, Garcia-Gonzalez is an undocumented immigrant whose status under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program remains in jeopardy. DACA, which then-President Barack Obama introduced via executive order in June 2012, protected individuals who entered the U.S. unlawfully during their childhoods from deportation and allowed them to seek legal employment. This past September, however, President Donald Trump terminated the measure, giving Congress a window of six months to find a permanent solution.

“Every day, my heart is in my throat,” said Garcia-Gonzalez, who was born in Uruguay. “I continually find myself asking, ‘What is he going to do now?’ I fear being deported into a country that I don’t remember and don’t know.”

Garcia-Gonzalez added that although she initially felt “worthless” in the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election, when she said students yelled slurs and shouted pro-Trump slogans in front of La Casa, the Spanish language Living Learning Community, she also received an outpouring of support.

“So many students came up to me or wrote reassuring messages in Foco or Collis after the election,” Garcia-Gonzalez said. “It made me realize that my voice matters and it is important for me to speak.”

The DREAM Act, a proposed piece of legislation that would provide a path for those eligible under DACA toward lawful permanent residency status in the U.S., has been debated fiercely in Congress for 16 years but has failed to pass multiple times.

Though 34 House Republicans and all 193 House Democrats have expressed interest in solving the DACA issue before the six-month deadline coming up on March 5, no single solution has been agreed upon.

Trump has also expressed that a permanent DACA solution will need to be tied to new immigration laws and funding for his proposed Mexican border wall.

But Garcia-Gonzalez, who moved from Uruguay to the United States when she was 6 years old, believes that her life, as well as the lives of her fellow undocumented immigrants, should be worth more than a bargaining chip in Washington, D.C.

“DREAMers, including me, are worthy,” Garcia-Gonzalez said. “I speak English fluently and I have worked to assimilate into society. But my mom, a stay-at-home parent who has spent her time raising a family, is worthy as well, and so are millions of other undocumented Americans.”

Garcia-Gonzalez, who spent most of her childhood in Gwinnett County, Georgia, the state’s second-most populous county, grew up in a poor but nurturing household.

“We often struggled to make ends meet,” Garcia-Gonzalez said. “Sometimes, we even stole donations from the Salvation Army parking lot in order to get clothing and other household items that we would not have otherwise had.”

Garcia-Gonzalez learned during her first year of high school, a year-and-and-half into Obama’s first term, that she had entered the U.S. unlawfully as a child. Her undocumented immigration status felt like the missing puzzle piece in a childhood that had perplexed her at times.

“I was conditioned to live in the shadows,” she said. “I was taught not to go out at certain times of the month, the week and the day. For example, my parents told me not to go out on the weekends because the police often do many DUI stops at that time.”

Despite her difficult upbringing, Garcia-Gonzalez graduated from Berkmar High School at the top of her class in 2014. She had been in her district’s program for gifted students since elementary school, and she took 14 Advanced Placement courses at Berkmar.

Garcia-Gonzalez had intended to attend a public college or university in Georgia, but she learned during her senior year of high school that Georgia’s laws excluded her from applying. Georgia’s Board of Regents, the state’s education policy decision-makers, enacted a policy in 2010 that banned undocumented students from attending the five top public universities in Georgia and forced them to pay out-of-state tuition at Georgia.

“My friends were applying to [the Georgia Institute of Technology] and [the University of Georgia] and all of these other places, but that wasn’t an option for me,” Garcia-Gonzalez said. “So, I decided to apply to community college with the mantra that, ‘It’s not where you start, it’s where you end,’ because I hoped to finish my education somewhere better.”

Although Garcia-Gonzalez was accepted into community college, she ultimately decided to take a gap year and join Freedom University Georgia, a college preparatory school and nonprofit organization that strives to improve undocumented students’ access to higher education.

“I went across the country with Freedom University Georgia to speak and share my story during my gap year,” Garcia-Gonzalez said. “We encouraged many schools to change their policies.”

Garcia-Gonzalez applied to nine institutions of higher learning during her gap year, and learned of her acceptance to Dartmouth on March 31, 2015.

“Dartmouth was my top school, and it was also the one that seemed like the furthest reach,” she said. “But I got in, and that year, I went with my family in our minivan on the 27-hour drive from Georgia to Dartmouth.”

Garcia-Gonzalez is a geography major and global health minor at Dartmouth. She juggles four campus jobs: supervisor at Novack Café, undergraduate adviser in Butterfield Hall, student intern at the Office of Pluralism and Leadership and film projectionist at the Hopkins Center for the Arts. In her free time, Garcia-Gonzalez serves as the co-director of CoFIRED, the Dartmouth Coalition For Immigration Reform, Equality and DREAMers.

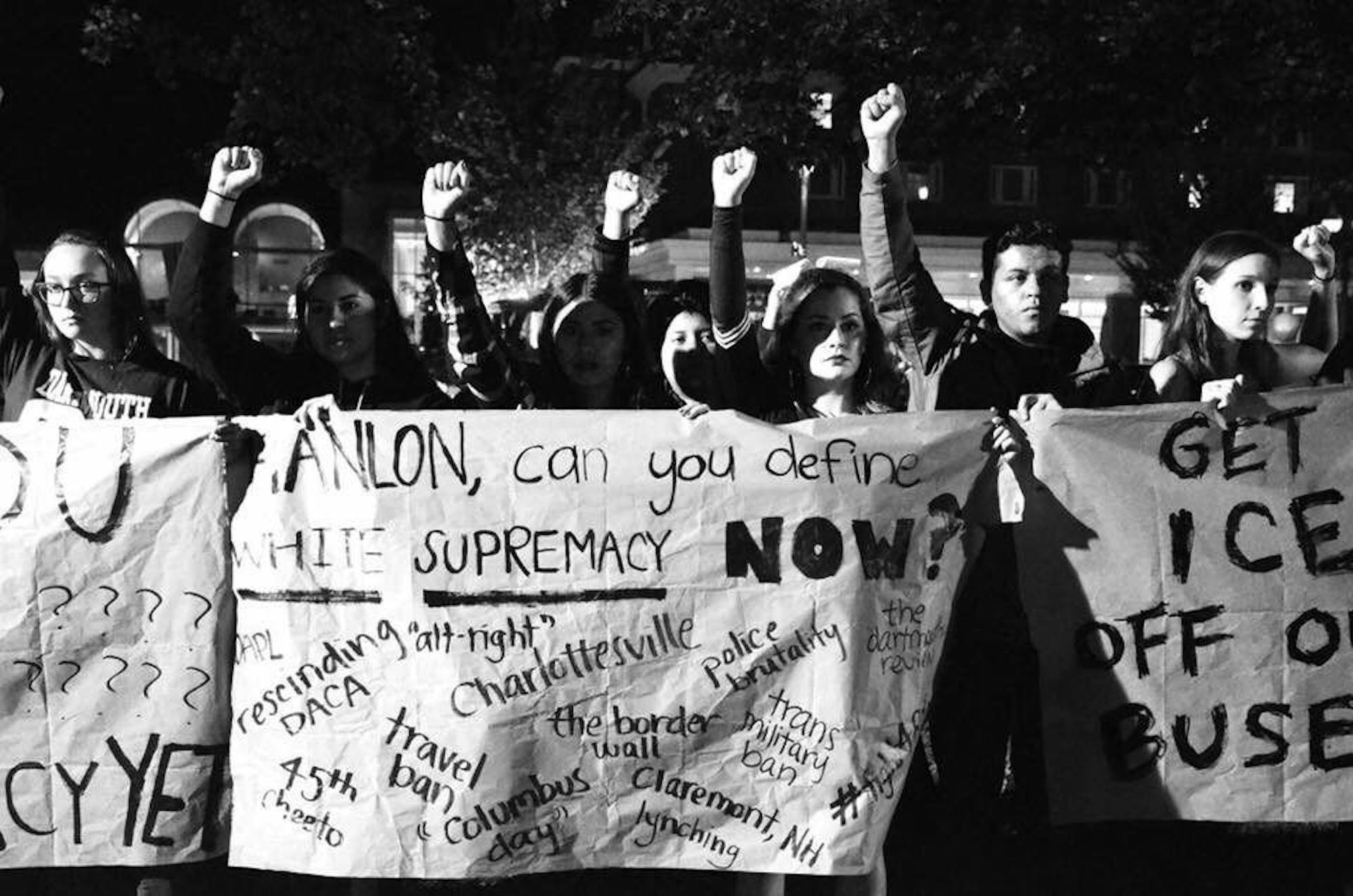

As the co-director of CoFIRED, Garcia-Gonzalez helped to draft a letter in response to College President Phil Hanlon’s statement on Sept. 5, 2017 after the Trump administration scrapped DACA.

“[We] will do everything in our power, within the bounds of the law, to support these members of our campus community most directly affected by potential changes and challenges to our nation’s immigration laws and will continue to decline to disclose information about students except as required by law,” Hanlon said in his statement.

Garcia-Gonzalez contends, however, that current U.S. immigration law is the problem because it leaves undocumented students at Dartmouth vulnerable to deportation.

“When President Hanlon and the administration said that they would ‘do everything … within the bounds of the law,’ I thought that was [ridiculous],” Garcia-Gonzalez said. “Why is Dartmouth going to follow current immigration law when people’s lives are literally at stake?”

CoFIRED’s letter called upon Dartmouth’s administration to provide legal counsel and additional financial aid for undocumented students because they cannot work legally. It also asked that the College declare, along with Safety and Security, that they will not cooperate with Immigration and Customs Enforcement in localizing and detaining students.

Similarly, Garcia-Gonzalez hopes that Dartmouth’s alumni will use their power and connections in order to create a permanent solution for DACA recipients. For example, five Dartmouth graduates currently serve in the United States Senate, including Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand ’88 (D-NY), Sen. John Hoeven ’79 (R-ND), Angus King ’66 (I-ME), Rob Portman ’78 (R-OH) and Tina Smith TU’84 (D-MN). Garcia-Gonzalez also believes that Americans should recommit themselves to expanding opportunities for marginalized groups and valuing, rather than scorning, diversity.

“The ‘American Dream’ is a fallacy today, and it is often used to divide people on lines of race or class,” Garcia-Gonzalez said. “Many people in this country don’t have the boots, so how can they pull themselves up by their bootstraps? I might seem like an example of the ‘American Dream’ because I’ve gone from stealing Salvation Army donations to the Ivy League, but most people do not have the same opportunities that I’ve had.”

Garcia-Gonzalez encourages Dartmouth students, faculty and alumni to become more informed about immigration issues and to use their personal platforms to raise awareness.

“At the end of the day, individuals have a choice to care, and I hope that they do,” Garcia-Gonzalez said. “People have an opportunity both to express their support for these issues and to give undocumented students a platform by handing over the microphone.”

Correction Appended (Jan. 18, 2018):

The Jan. 17 article "Bump: Valentina Garcia-Gonzalez '19, a journey" has been updated to more accurately reflect Garcia-Gonzalez's position in CoFIRED.