As the College prepares for an influx of political attention during next year’s presidential election season, professors will face personal decisions about which, if any, of the candidates to support in a crowded field.

Although the College’s academics have historically given more money to Democratic candidates, professors and students said they do not expect that campus’ professors will inflect their teaching with personal political philosophies.

Editorial and communications director at the Center for Responsive Politics Viveca Novak said that donations from academics are an overwhelming source of political money for candidates, but they often remain overlooked.

She said that professors usually donate to Democratic candidates. Dartmouth, she said, is one of the few colleges that the Center has looked at where contributions sometimes trend toward Republican candidates.

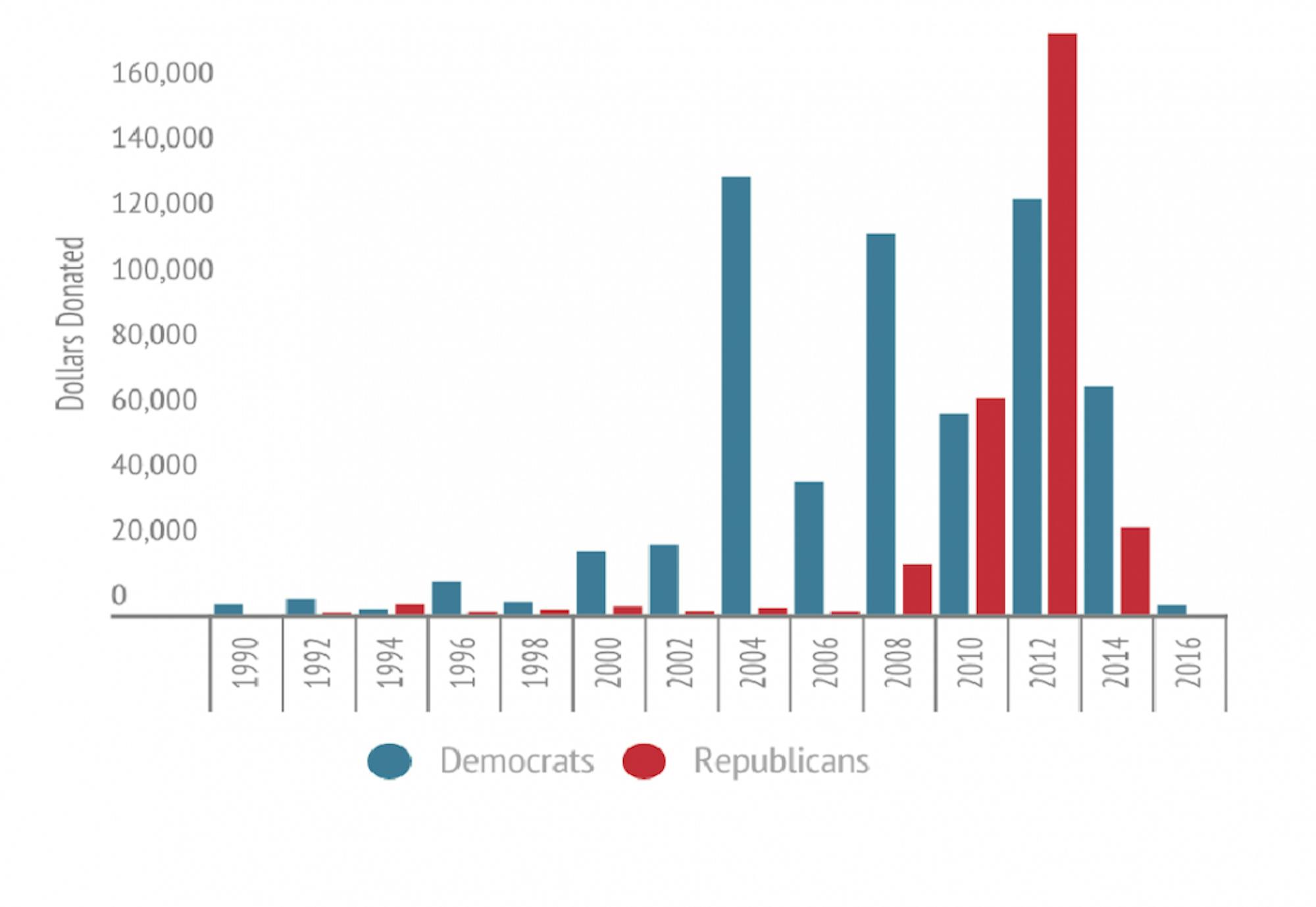

In 2008, 88 percent of the $132,293 donated by people employed by or affiliated with the College went to Democrats and 12 percent went to Republicans, Novak said, citing the Center’s publicly available donation data. In 2014, 70 percent of the $100,084 donated went to Democrats and 27 percent went to Republicans.

In 2010, however, 46 percent of the $132,476 donated went to Democrats and 50 percent when to Republicans, and in 2012, people affiliated with the College donated a record $308,017 — 58 percent to Republicans and 41 percent to Democrats.

While Dartmouth employees and affiliates have donated exclusively to Democrats so far this year, Novak said not much money has been given yet. Just $2,700 was donated by March 15, compared to the more than $300,000 donated by the end of the 2012 presidential campaign cycle.

Of all firms and institutions tracked by the Center for Responsive Politics, Dartmouth’s employees have given the ninth most total donations to Vermont senator and presidential hopeful Bernie Sanders, as of July 21.

Employees and affiliates of the College have given more to Sanders’ campaign than employees of any other Ivy League institution. Employees and affiliates also gave more than those who work for large institutions like Merrill Lynch, Amazon.com and the United States Postal Service.

Employees and affiliates of the College do not crack the top 10 for Hillary Clinton, Martin O’Malley or any Republican presidential campaigns. Employees of Yale University have given the fourth most to Clinton’s presidential bid.

Still, Dartmouth employees’ donations as a whole skew toward Democrats.

In the past 15 years, just 12 percent of professor donations went to Republicans, but 73 percent was donated to Democrats. In 2014, 63 percent of donations were funneled to Democratic candidates, while 33 percent made its way to Republican candidate.

Four College professors interviewed said that they do not think personal politics play a role in the pedagogy of their departments. They disagreed on whether revealing their personal politics to students is acceptable.

Government professor John Carey said that while there are many government classes that deal with normative questions, those classes tend not to focus on current campaigns.

He said that in courses that do focus on current campaigns and draw from current events, their central discussions do not involve how students should vote.

Most political professors both at the College and nationally are Democrats, Carey said, but he stressed that as a result of the questions being asked in government classes, a political scientist’s own views are not relevant to the scholarship, reading and discussions taking place.

“Academic scholarship tends not to be partisan,” he said.

He said that he does not hide his political affiliations, but he does not present them either, unless he is asked a question that would betray his partisanship.

Sociology professor John Campbell said that he does not answer questions that would reveal his political leanings, although he does teach a few courses that involve political topics.

“My job is to present different theories and data that students can use to make up their own minds about whatever the political issue might happen to be, not to stand up there and advocate for one position or another,” Campbell said.

He said that while he is sure his preferences may somehow permeate his teaching, he does his best to keep them out.

Mathematics department chair Dana Williams said that since mathematics are devoid from politics, there is no reason why his politics should arise in a math class — although he will occasionally make a political joke.

Because professors hold a position of authority, he said that he believes revealing his political affiliations could make students uncomfortable. Williams said, however, that it could be more difficult for professors teaching classes related to politics to keep their opinions to themselves.

Public policy professor Ronald Shaiko noted that there is not a set campus policy about disclosing personal politics. His view, he said, is that by the end of the term, he thinks students would have a hard time figuring out where he stands politically.

“I don’t think it’s our job to indoctrinate [students] into any political philosophy,” he said.

At the beginning of his class “Introduction to Public Policy,” Shaiko said, he gets a sense of where each student in the class stands politically. That way, if the class skews in one direction, he can act as a balancing force.

Although both the majority of “Introduction to Public Policy” students and Shaiko himself tend to be moderates, Shaiko said it is important of students of all political beliefs to feel comfortable.

Shaiko said, however, he thinks his moderate political views make it easier for him to teach his public policy classes.

“It’s easier for me not being an ideologue to teach public policy,” he said. “I don’t have a vested interest in either party, so the way I teach is how can we make it better. If it’s a Democratic plan or a Republican plan, as long as it makes policy better, I’m for that.”

Shaiko said he has nothing against faculty members with distinct political point of views as long as they clearly delineate these to their students, so that students are not indoctrinated into those views unknowingly.

College Republicans president Michelle Knesbach ’17, an economics and government double major, said she is not concerned that there are fewer Republican faculty at College than Democratic faculty. She thinks there is a “fair lack of polarization” in the government department.

She said she thinks that to whom professors donate money politically is less important than their commitment to unbiased teaching. As a result, professors’ political leanings have not affected her time at the College, she said.

“Professors do a really good job of committing to the promise of not having a political bias or influence in the classroom,” she said.

Charlotte Blatt ’18, a government major and member of the College Democrats’ executive council, also said that her professors’ political affiliations do not matter to her.

“I assume that if you are [a faculty member] at Dartmouth, you’re an incredibly smart person who has so much to share with students, regardless of political affiliation,” she said.