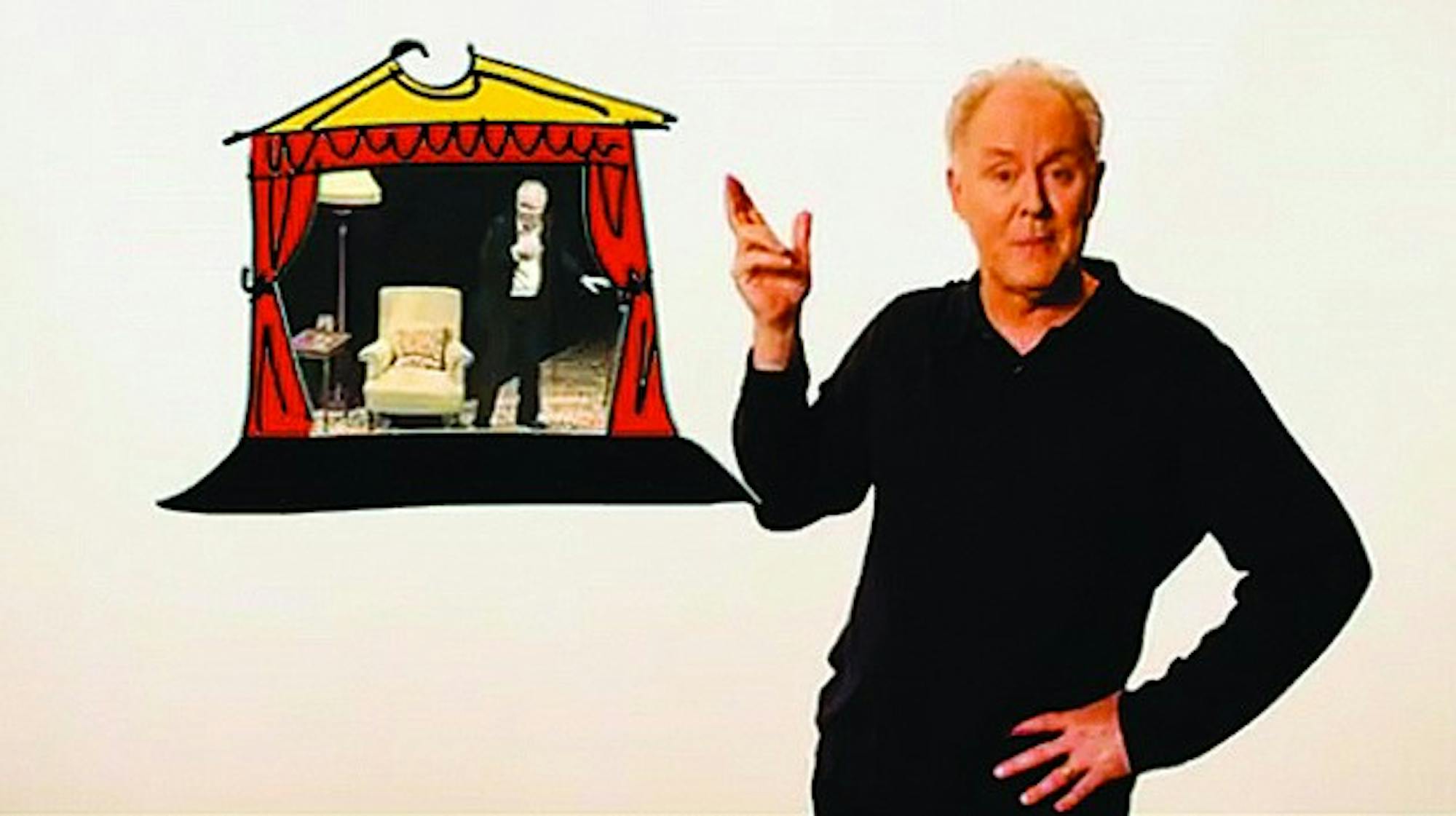

The show featured two acts, each of which began with lighthearted fare before the lights dimmed and the audience adjusted to Lithgow's more formal storytelling. In both acts, Lithgow fused his own personal history with the reimagined telling of stories that he heard as a child and that he read to his father in his last months of life, acting out characters on a minimally decorated stage.

"I've never been here before, and I feel like I've swallowed a Dartmouth horse pill," Lithgow said at the beginning of the show.

Lithgow introduced his performance by recounting his afternoon of exploring the art in the Hood Museum of Art, attending the Sacred Heart University football game and eating maple gelato at Morano Gelato. Honored by the opportunity to perform in the Hopkins Center, Lithgow said it was a chance he's "been waiting 50 years to do."

Before beginning his storytelling performance, Lithgow posed a rhetorical question to the audience, asking them, "What the hell is this?" He said that the evening would focus on stories, which would be layered as stories within others. The various stories that Lithgow recounted connected to his life, influencing his abilities as a storyteller today, he said.

"Why are all of you even here tonight?" he said. "You all look so eager and hopeful! What are you hopeful for?"

He recounted the "exuberant flamboyance" of his father, Arthur Lithgow, a quality that he has inherited, as demonstrated through his performance. This theatrical flair came through during the two-hour performance Lithgow's energy never waned, and his ability to transition from colloquial banter with the audience to the actual scripted performance was seamless.

In the first act, Lithgow acted out the 10-plus characters, including a parrot, of P.G. Wodehouse's story "Uncle Fred Flits By." In the second act, Lithgow took on the persona of the barber in Ring Lardner's "Haircut." The telling of these tales certainly mirrored Lithgow's trip down memory lane. During Lithgow's childhood, his father read him these stories, acting out the parts, Lithgow said. The vigor with which Lithgow spoke in recounting these memories truly evoked vivid images for the audience despite the sparse set of the stage.

Lithgow's description of the "scratchy, burnt-orange sofa" and his father's uniform of "short-sleeved, seersucker shirts" put the audience at ease, allowing his viewers to intimately relate to his story. During his performance, Lithgow adopted a persona akin to a cool, flashy family member recounting a crazy tale.

While Lithgow's heartfelt account of his father's last days were emotionally exhausting, he alleviated the tension with the liveliness with which he told Wodehouse's story. He said that it was his telling of the story that allowed his father to "rally" his personality during his last months. The Wodehouse story is the closest he has ever come "to finding an answer to the question" of why people want to hear stories, according to Lithgow.

During "Uncle Fred Flits By," spit flew across the stage as Lithgow inhabited the characters of the ostentatious, garish Lord Ickenham and the snooty Mrs. Parker. His ability to rapidly switch among the many characters was fantastic. In one instance, Lithgow opened and closed his legs to signify the character change between male and female, eliciting loud laughs from the audience.

Lithgow began Act 2 with a raucous, hand-clapping romp of a song entitled "Eggs and Marrowbones."

"I always like to kick off Act 2 with a peppy song about adultery and murder," Lithgow said.

Lithgow explained that during the show's first incarnation, Act 2 did not exist, but audiences "were like little children at bedtime they wanted to hear another story," he said.

With very little stage transition, moving his sole prop of a book and chair around, Lithgow quickly transformed the quaint English village setting of the first act to an American barber shop in the Midwest. He recounted how "Haircut" reminded him of his childhood filled with "paralyzed shyness" upon moving to a new school in the Midwest, alleviated briefly by a seemingly friendly boy named Denny. Lithgow went on to explain an unfortunate, horrific "hazing ritual" that involved Denny and his gang squeezing Lithgow's genitalia in a stairwell during a game they called "Squirrel." Lithgow presented this juxtaposition of things both funny and horrific as the inspiration for choosing Lardner's story "Haircut" for the second act.

Lithgow emphasized how "Haircut" unfolds during the course of a regular customer's visit to the barber shop, though we only ever hear the voice of the barber. He compared the silent customer of the story to us, his "captive audience."

"There are those who tell stories and those who listen," Lithgow said. "Why shouldn't the silent customer be you?"

Lithgow's telling of "Haircut" was dominated by the maniacal, hyena-like laughter of his barber character. The amount of emotion present in each one of these frequent laughs was at times both nerve-wracking and hysterical, yet Lithgow's precise, calculated mannerisms informed which reaction was proper.

Act 2 was a truer indication of Lithgow's amazing talent as an actor, carrying us through a haircut by realistically miming the actions as he told us the story. Unlike "Uncle Fred Flits By," which had multiple character dialogues, the barber was the only one to speak in "Haircut."

Ultimately, Lithgow's performance was truly mesmerizing. It was an effective musing on the art of storytelling. Lithgow could have picked the simplest of narratives and still would have infused it with as much life as he did the performed tales.

In answer to Lithgow first question to the audience "What the hell is this?" in a word, this was awesome.