During the 1970s, the College began deliberately increasing its accessibility to prospective students of minority and low socioeconomic backgrounds. Over the course of the subsequent decade, the focus shifted to diversifying the faculty, an issue with which the College still struggles, according to Vice President of Institutional Diversity and Equity Holly Sateia '82. By the 1990s, the process of building a diverse student body and faculty was underway, and the College was devoting itself to creating communities and encouraging dialogue across campus, Sateia said.

"The current conversation has evolved to address how the College can create the most optimal learning environment on campus so that all students don't just arrive but thrive," Sateia said.

The College's team of admissions officers has successfully maintained diversity within the student population, acting Dean of the College Sylvia Spears said.

"I am so impressed with what [Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid] Maria Laskaris and her team have done over a few years in terms of bringing in this incredible group of students to Dartmouth," Spears said. "Now we need to make sure that every one of those students feels that they are successful, that they have a wonderful experience that they would want to go home and tell everyone about."

Despite some initiatives, the College has failed to recruit a faculty whose composition reflects the demographics of the student body, which Samantha Ivery, acting director of the Center for Women and Gender and adviser to black students, said is key to a positive college experience.

"Our students don't necessarily see themselves reflected in the classroom," Ivery said. "If we create a pipeline where people of color are successful, then we'll attract those people."

Spears, who is both black and Native American, also admitted that the student community has become more diverse than the faculty.

"I think we should aspire to have the same kind of diversity in our faculty as in our student body, and I think we've made some good progress," she said.

Since 2003, Dartmouth's proportion of minority students has increased from 28 to 34 percent, according to the College's annually compiled Common Data Sets. But faculty statistics do not reflect the same trend.

Of the 675 faculty members employed by the College in 2009, 14 percent reported a minority background. This figure represents a 3 percentage point increase from what was reported in 2003.

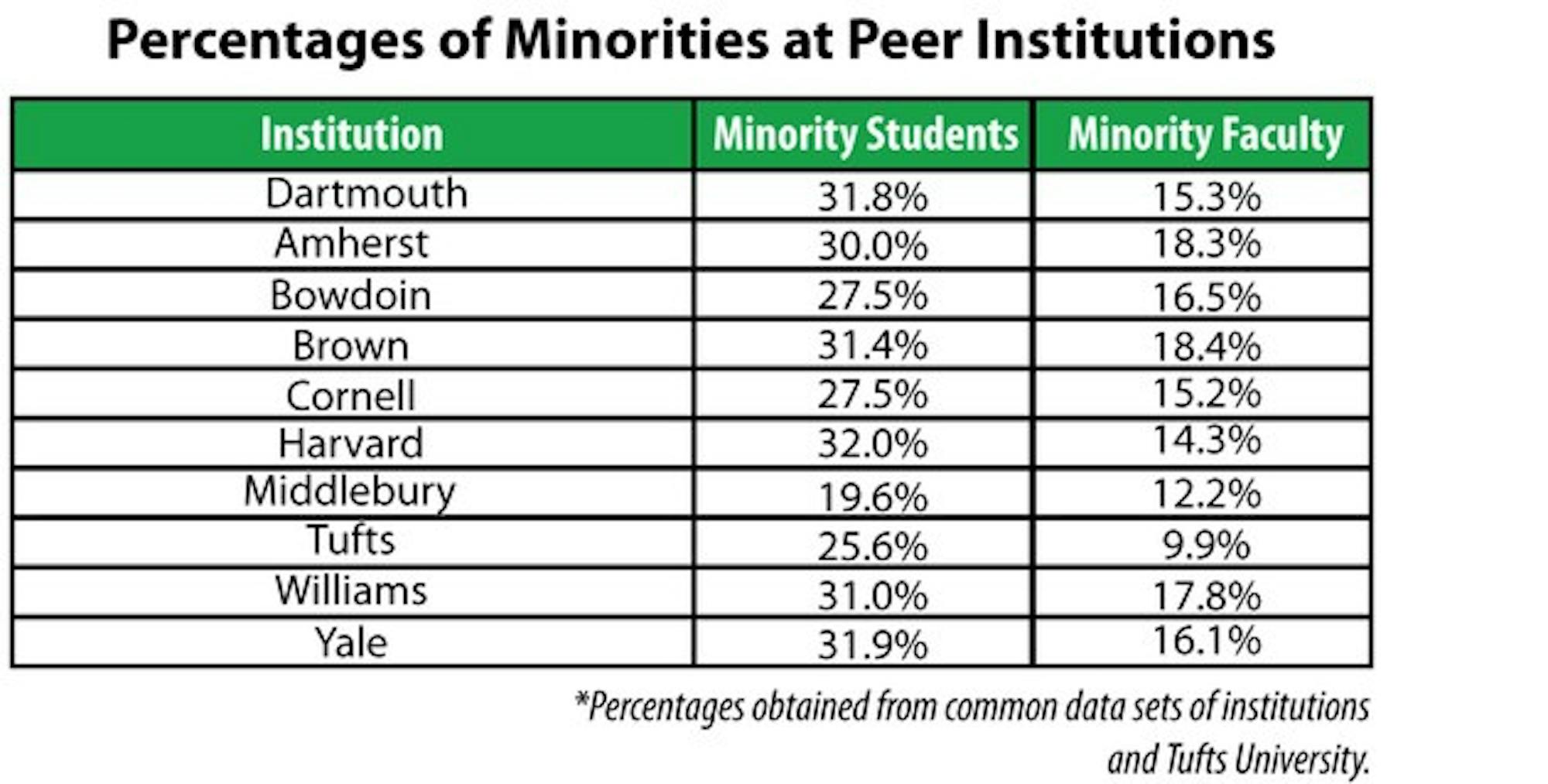

A comparison of student and faculty composition figures from the 2008-2009 Common Data Sets released by other northeastern colleges and universities suggests that Dartmouth exhibits a high number of minority students, but falls within the middle to low range in terms of minority faculty.

MAINTAINING FACULTY DIVERSITY

Potential faculty members may be deterred by Dartmouth's small size and isolated location, President Emeritus James Wright said in an interview.

"Individual faculty and staff make decisions based on career projections, family and other things that come up," Wright said. "We don't want anyone ever to feel they weren't welcome here. If they determine this isn't quite their place, that's OK."

The homogeneity of New Hampshire and Vermont may discourage minority professors from accepting positions at the College, said Bruce Duthu '80, chair of the Native American studies department.

"When I talk to possible Native American [faculty] recruits and I talk about moving to Hanover, I get this look of Are you kidding me?'" Duthu explained. "Though people may be drawn to working at an Ivy [League school] in a top program, they don't think the quality of life will suit them."

While bringing faculty members of color to campus is difficult, retention is an even greater issue and must be considered during the recruitment process, said Antonio Tillis, chair of the African and African-American studies program.

"It seems like the majority of minority faculty members leave after a few years," Assistant Dean of Student Life Pamela Misener said. "It's hard to generalize, but some may be drawn back to family, realize that the research base is not what they thought it would be or find that the environment is too stifling."

Retention of minority faculty members is also affected by competition with other prestigious institutions.

"We're in competition for those junior faculty in terms of keeping them here to become senior faculty," Sateia said. "They're often recruited to other places before the tenure decision comes up."

But the College is actively seeking to increase the ethnic and cultural diversity of its faculty, Dean of the Faculty Michael Mastanduno said.

"A commitment to diversity is built into the process," Mastanduno said. "It's fair to say that most departments are acutely sensitive to creating a diverse interview pool."

THE STUDENT EXPERIENCE

Many students interviewed by The Dartmouth said faculty of color contribute to the community both by providing alternative perspectives and acting as role models for minority students.

Education professor Andrew Garrod said the College must emphasize building an ethnically varied faculty to mirror the increasingly diverse student body.

"The perspective of faculty of color is extremely important," Garrod said. "You want them as models that other people can aspire to so that they may say, I can envision myself as a college professor.'"

Kyle Battle '11 said that his academic experience has been influenced in part by perceptions of race.

"Once I got here, especially because I'm usually the only black male in my class, I felt like I was speaking for the black race," Battle said. "I don't think that's fair, but I embrace educating others."

Battle spoke of a fellow black student who was once asked by a professor how slavery affected him personally.

"That was 200 years ago that's not fair to ask," Battle added. "I couldn't pinpoint the root of the problem there, but it's not racism. I honestly think it's ignorance. People aren't sensitive to certain things."

But Battle said it was a positive step that Spears and College President Jim Yong Kim, a Korean American, are minorities.

"It says a lot that two of the most powerful people at Dartmouth are not Caucasian men, because if you look at the history of the school, that's what it's been for the most part," Battle said.

Many professors and students said celebrating diversity can combat categorizations based on racial differences.

"There is a value in making difference visible," Spanish professor Rebecca Biron said. "Celebrating diversity is an ethical response to the fact that we live in a world that non-theoretically creates a hierarchy. It's a resistance to that."

Adding a distributive requirement for class in an interdisciplinary department could help facilitate this visibility, some students said. Other students and faculty members said that awareness of diversity cannot be forced upon students.

"I tend to think that the benefits, long-term, are more sustaining if the classes are not imposed," Duthu said.

Students said they valued the classes they had taken in interdisciplinary departments and expressed an interest in taking more in the future.

"We oftentimes will see someone and place them within the categorization of our [ethnic] understanding, irrespective of the way that they self-identify," said Tillis, whose AAAS classes focus on the triangulation of race, class and gender. "Because at Dartmouth many students identify with multiple backgrounds, these classes help other students understand these challenges."

The respectful, intellectual dialogue that takes place within the classroom must also be applied to other settings to foster communication among various campus groups, according to students and faculty.

"You're going out into a world where people have very different assumptions, and it happens here on campus as well," College President Jim Yong Kim said in a July lecture. "It's about finding ways to start here, developing your empathy muscles, which you'll use for the rest of your life."

PROGRAMS AND RESOURCES

Several initiatives have been implemented to provide current minority students with resources and create a "pipeline" to attract new minority students and faculty to the College, according to administrators.

Shortly after Sateia created a Diversity and Equity Plan for the Office of the Dean of the College, then-College President Wright asked that it be instituted in every department.

The Office of Pluralism and Leadership, established in 2001 at Wright's behest, houses the Asian and Asian-American, Black and African-American, international, Women and Gender, LGBTA, Native American, and Latino student advisers.

The First Year Student Enrichment Program now in its second year was created to ease the transition from high school for first-generation college students, most of whom are minorities, according to Frankie Herrera '13, who participated in the program and returned as a mentor this year.

"It has given me a reason to smile on the days where everything is going wrong," Herrera said. "It has given me the network of people where, if I'm having a bad day and I see one of the people from FYSEP, they will stop and know something is wrong. We're all there for each other and support each other."

ACADEMIC DEPARTMENTS

The College's efforts to highlight mutual understanding have led to the creation of interdisciplinary programs that focus on other regions of the world and their peoples.

The Latin American, Latino and Caribbean Studies department which only became a permanent department in 2006 was first introduced at the College as "Latin American and Caribbean Studies" in 1993. Latino Studies was added to the program in 1997.

As an interdisciplinary program, LALACS crosses traditional academic boundaries and covers a broad range of aspects related to the geographical areas that fall under the department, Biron said.

"People think it's a cultural identity studies program, but it's not," Biron said. "LALACS is very self-consciously an area studies program in order to point out that there are other parts of the world that don't have to consider themselves marked [to be studied in terms of culture]."

In 1997, visiting history professor Vernon Takeshita taught the College's first two Asian-American studies classes, focusing on the Asian-American experience before and after World War II, according to history professor Jean Kim.

In response to a student petition, the administration formed an Asian-American Studies Initiative Committee with the intention of developing a minor in the field, Kim said. Based on the committee's recommendations, a senior scholar was hired to join the Asian-American Studies faculty, but he soon returned to his position at another institution.

"AAS has been kind of rocky, in part because of turnover," Kim said. "The manpower has been either absent or partial, and it's been difficult to have any kind of continuity and coordination."

The Asian and Middle Eastern Studies program now gives students the option to concentrate in Asian-American studies and encourages students to perform independent study, engage in research projects and write theses within this concentration.

"We're trying to maximize the resources that we do have," Kim said.

The interdisciplinary nature of the College's African and African-American Studies program which was originally called "Black Studies" reflects the "genuine support for thinking across departmental lines," English professor Soyica Colbert said in a 2009 Dartmouth Life article.

"As scholars and students of African and African American studies, we've come to a point where it's appropriate to take stock and to examine the state of the discipline," Colbert said, reflecting on the department's position as being one of the oldest in the nation.

The Native American Studies department, which began in 1972 with two course offerings, now offers between 18 and 20 courses a year, according to Duthu. The department celebrated its 30th anniversary in 2002.

"We bring long-ignored, but critical, stories to the table," Duthu said. "Telling American history without telling Native history not only short-changes the reader, but short-changes the entire country."

Duthu said the department's focus on interdisciplinary learning allows students to connect the knowledge sets they acquire in different classes, demonstrating the aim of the liberal arts experience.

But beyond that, interdisciplinary courses can show students that despite regional, racial, ethnic or socioeconomic differences, there are fundamental realities that all people face.

"In order for people to address the problems of the world, they need a level of cultural competence and ability to exchange across difference," Spears said. "We need to be able to find the common ground. No matter where we come from, there are some basic elements of the human experience that are common."

Staff writer Marina Villeneuve contributed reporting to this article.