"They want us to fail," he told me. "We have classes where the average score after a five point curve is a 65. And it's not because people are stupid."

I thought instantly of columns that have appeared in The D recently about median grades and the non-recording option, topics that hinge on the way Dartmouth students are motivated by their crippling fear of any grade less than A minus. In "Over the Median," May 12, Julian Sarkar '13 argued that the inclusion of median grades on official transcripts encourages students to seek out only classes that they are guaranteed to succeed in. In "NRO Life, Minus Econ," April 20, Kevin Niparko '12 stated that the unwillingness of certain departments to allow NROs was stifling intellectual curiosity and liberal arts exploration.

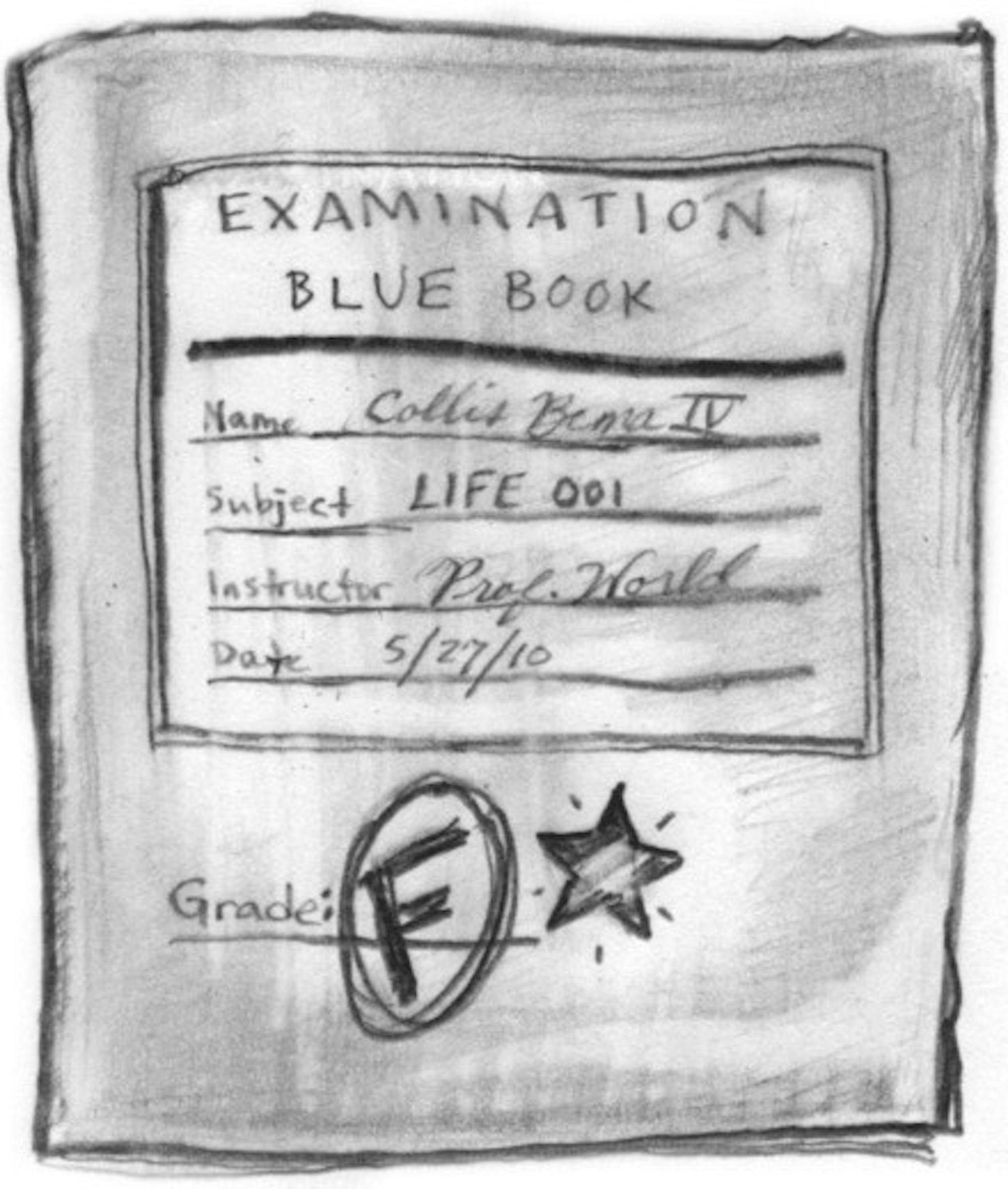

Both Sarkar and Niparko seek more leeway for failure, but they also want a system that allows this failure to be hidden away, tucked behind an NR or the absence of a median grade. Give us the chance to explore, and perhaps fail, the argument goes, just don't let graduate schools and future employers know about it. And for the most part, Dartmouth indulges this approach. The College provides countless ways for students to avoid genuine failures, from the withdrawal option to actually not allowing the grade of "F", preferring instead the far less menacing letter "E."

This method of contained failure made sense to me at first. Talking to my cousin, though, I began to wonder if we have it all wrong. What if, rather then helping students mask their missteps, Dartmouth encouraged its students to fail fantastically, in undeniable, unmistakable ways? What if Dartmouth taught us how to fail, but with grace, dignity and the wisdom to learn from our mistakes?

The world's most successful people have proudly proclaimed their failures for centuries. Often, they have done so in the context of attributing their success to their many prior failures. Failing taught them important lessons about what they were doing wrong, as well as what they had done right. Their willingness to fail allowed them to take major risks, which paid off with major results. Thomas Edison's famous remark, "I've not failed. I've just found 10,000 ways that don't work," can be found on inspirational posters in elementary schools across the country. Everyone knows that Bill Gates is the world's most successful college dropout.

And yet, we cannot seem to let go of our ideal of perfection, of the 4.0 and the well-rounded extracurricular resume and the prestigious internship and the subsequent prestigious job offer. Most of us at Dartmouth have never experienced true failure in our lives, and we don't plan to start, either, thank you very much.

The problem is that, in the real world, drive, determination and talent don't always lead to success on the first try, and they don't always guarantee it in the long run. Just ask the Class of 2010, who through no fault of their own are now searching for jobs in the worst economy of the last several decades.

Facing bleak prospects, the people who succeed are those who are willing to take risks to try unexpected career paths that they never imagined for themselves, or to start their own companies out of their parents' basement. The people who struggle in these conditions are those who are paralyzed by the fear of trying something unfamiliar, at which their success is not guaranteed. It is interesting to note that in Israel, where my cousin ultimately did fail one of his classes, risk-taking is a culturally engrained virtue, and one that pays off in ways we might predict Israel has the highest number of start-ups per capita of any country in the world.

Being set up to fail is a terrifying concept, and certainly one that would cause the average Dartmouth student to recoil in fear. If we can't even bring ourselves to take classes with B medians, how could we possibly resign ourselves to an inevitable F? Frankly, I don't have the answer. I don't know how to make students accept failure, and I don't know how to make Dartmouth into a place that allows its students more room to fail. Perhaps most difficult of all, I don't know how to make American society into a place where potential employers don't see an F on a transcript as an immediate disqualification from a job offer. But if we ever do find away to make failure more culturally acceptable, learning to fail could be the most important lesson that Dartmouth ever teaches.