On Sept. 29, award-winning writer Jacinda Townsend delivered the Cleopatra Mathis Poetry & Prose Lecture at Sanborn Library. This annual lecture series was created in honor of the founder of Dartmouth’s creative writing program, Cleopatra Mathis, to connect students to literary figures.

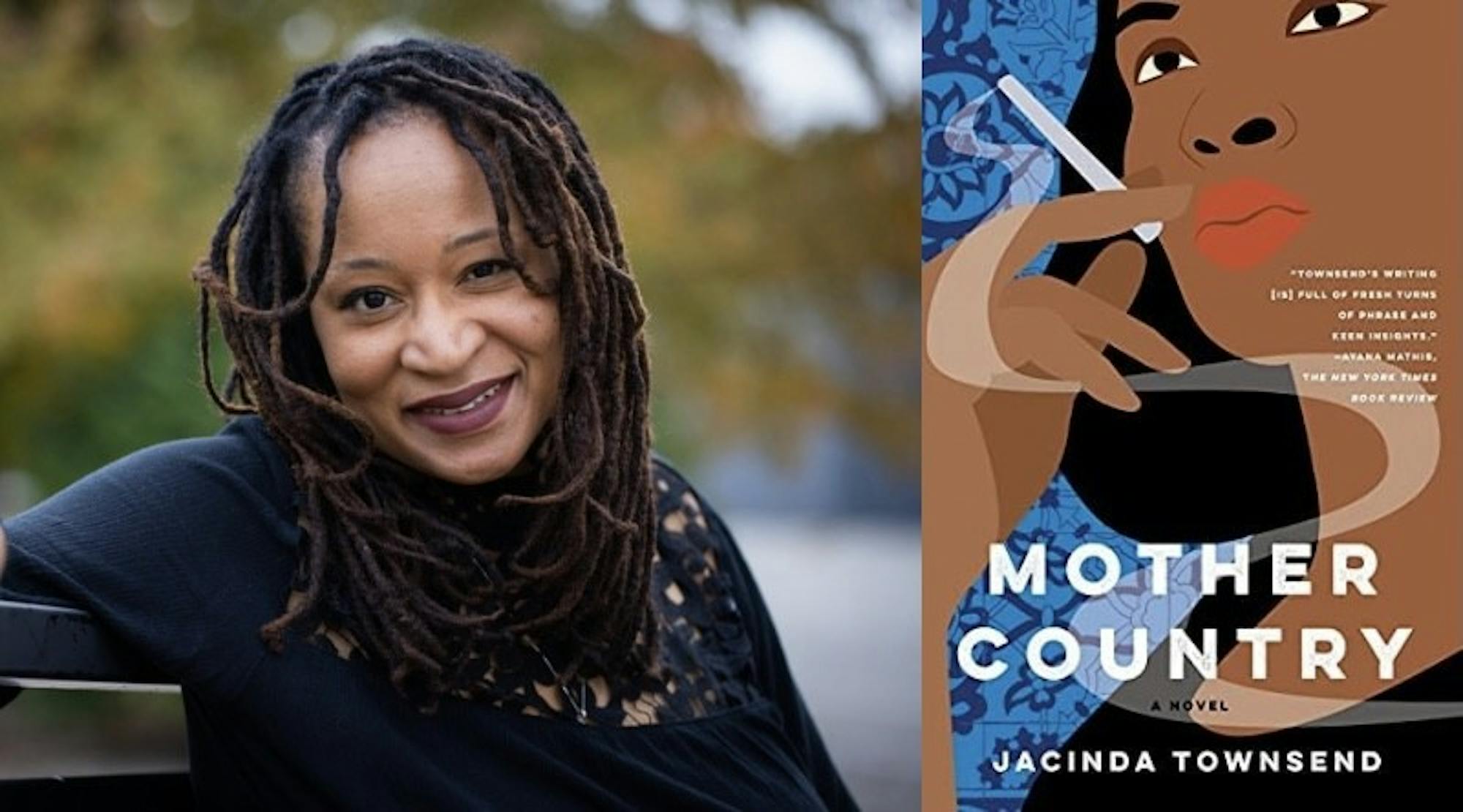

Author of the novels “Saint Monkey” and, most recently, “Mother Country,” Townsend has been awarded the Janet Heidinger Kafka Prize and the Fenimore Cooper Prize for her work exploring themes of kinship, control and place. Speaking to the mission of the lecture series, Townsend gave insight into the role of the author and why crafting characters is the most important part of the novel-writing process.

In his introduction to the lecture, English professor Thomas O’Malley — who was a classmate of Townsend in the MFA program at the University of Iowa and invited her to speak at the College — wrote that Townsend’s work explores the concept that “nothing in our lives but our actions belong to us.”

Townsend’s first question to the audience was, “What do you think is the foundational aspect of [writing]?” No listener produced the answer Townsend was looking for: character. Townsend explained that while she was earning her MFA, she learned from her professors that character is the apex of the novel, above all else. Crafting characters — the art of going beneath their “[skin],” as she commented — creates the foundation for stories.

Townsend’s second question showcased the creative thinking she is renowned for: “How many of you think you could kidnap a child?” From there she moved to, “how many of you think you could watch someone kidnap a child?” She then revealed those were the questions she had while writing “Mother Country,” a story about a tourist abducting a child off the streets of Marrakech.

English department administrator Katherine Gibbel, who organized the event, commented on Townsend’s engagement with the audience.

“I really [admired] how she asked people questions mid-reading,” Gibbel said. “... so much of [Townsend’s] reading was about the implication of the reader and the use of the second person, and so prefacing reading those character sketches with that question … really situated her reading quite well.”

Townsend leans into the moral nuance with her characters. She tries to analyze scenes through a “pane of glass,” leaving the role of judgment to her readership. Townsend said that often the “worst villains are the ones that are trying to be good.”

Townsend said she maintains that the reader should be able to view their character depth through “indictment” — they are assessed from all angles and possible viewpoints, and no one is purely innocent or guilty.

An audience member asked whether Townsend feels as though she has the right to tell a story about Morocco’s relationship to slavery in “Mother Country” without personal ties to the subject. Townsend responded that she does not feel she has the right, and because she didn’t think she could write the novel solely from the perspective of a Moroccan living in Marrakech, she included characters from the diaspora, living in America.

“Journalism and all of the time that she spent in Morocco doing research for this novel is certainly significant to having a really well researched book and one she clearly spent a lot of time with,” Gibbel said.

Townsend also spoke to her role in politics, specifically as an elected school board member. She expressed remorse that more artists don’t run for public office, as the “matter of work [in the arts] is empathy — stepping into other peoples’ skins.” Even though Townsend went to law school and practiced as an antitrust lawyer, getting involved with politics was not something she expected. However, it has given her control within the space of social impact, beyond the page.

Victoria Yang ’26, who attended the event as a part of a creative writing course, said she left the lecture with revised thoughts about a writer’s ethical responsibility.

“Everything we do [as writers] is really centered around characters who are people,” Yang said. “[Townsend] playing with that moral question could also very well extend into her identity as a politician … [her] experiences writing people and the light and dark of the human spectrum can reflect in how she approaches her political life.”

This event was well received by the audience, which was mostly a mix of students and professors. Sophia Llibre ’26, who said she is interested in creative writing, found Townsend’s words inspirational, added that she wishes events like this were better advertised.

Yang added that she wants professors to extend these guest lectures into the curriculum.

“A class wherein every other week another writer comes in,” Yang said. “We are so busy…it’s very hard to schedule these things individually in your calendar.”

English professor Alexander Chee emphasized that the English department recognizes the importance of these lectures for students.

“[It] allows students to see more models for being a writer than just their faculty members,” Chee said. “ … I really believe in teaching students to face this world with the stories they want to tell, to consider the power of fiction to explore ideas and issues, not just to entertain.”