Since October 2021, Russia has deployed over 100,000 troops on the Ukrainian border, prompting heightened tensions with Ukraine and NATO and domestic calls for sanctions on Russian leaders and financial institutions. Dartmouth students and professors shared their insight into their ties to Ukraine, their views on the escalating situation and its international implications.

Russia and Ukraine have been engaged in an ongoing “hybrid war” since the Russian annexation of Crimea, a peninsula in southern Ukraine, in 2014, Russian department chair Victoria Somoff explained.

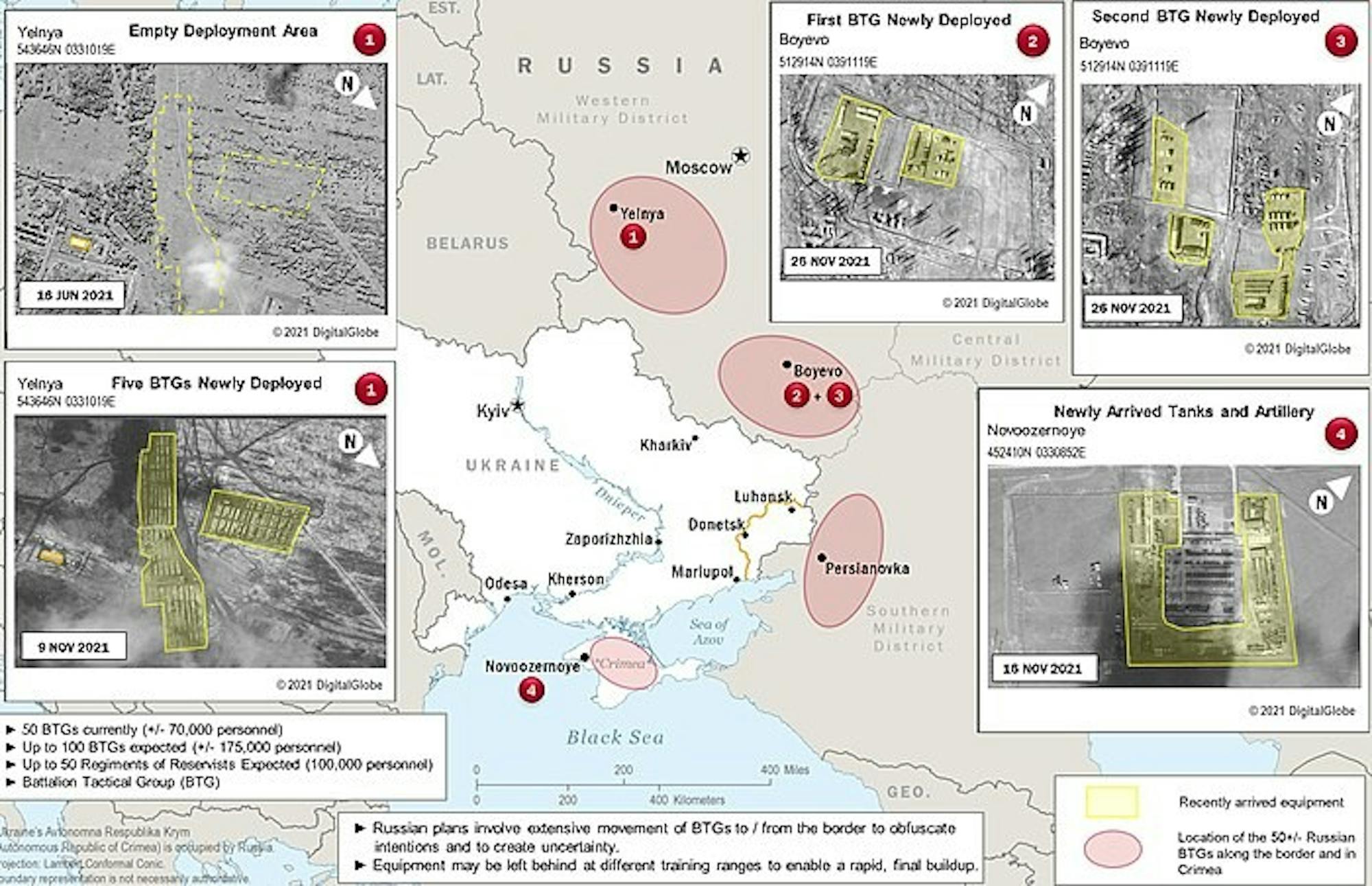

According to the Council on Foreign Relations, in recent years, Russia has deployed troops to the Belarus-Ukraine and the Russia-Ukraine borders and may be aiding Russian separatists in the eastern part of Ukraine. The CFR also noted that the U.S. remains committed to Ukraine’s sovereignty, does not recognize Russia’s claims to Crimea and provides military aid to Ukraine.

The outcome of the current tensions between Russia and Ukraine and the ongoing threat of invasion will have impacts on NATO’s role in the region, Europe’s natural gas markets and international law, according to reporting by the New York Times. This latest evolution in historically tense Russia-Ukraine relations has prompted strong reactions among members of the Dartmouth community.

Ukraine declared itself independent of the Soviet Union in 1991, Somoff said. She added that while part of the Soviet Union, Ukraine had “some kind of autonomy” but remained firmly under Moscow’s influence.

“Ukraine was always domineered and controlled by Russia,” she said. “Russian language, Russian culture, was dominant.”

Somoff explained that with Ukraine held “hostage,” Russia has claimed it will not invade if NATO, a trans-Atlantic defensive alliance of European and North American countries originally formed to oppose the Soviet Union, guarantees it will not extend membership to Ukraine. After the end of the Cold War, NATO expanded membership to several states in Eastern Europe, — including nations that have also faced aggression from Russia such as the Baltic states — and while it did not induct Ukraine, the alliance has said that NATO membership is open to the country.

Comparing the Russian threats to “blackmail on the international scale,” Somoff said she would advise NATO not to respond to them, arguing that while NATO is not currently considering Ukrainian membership, it should not rule out the prospect since Ukraine “needs protection sooner or later.”

Russian and government professor William Wohlforth said that, at a minimum, Russia wants to prevent Ukraine from joining NATO. At most, he said that Russia also may seek to ban NATO from deploying weapons and troops near Russia.

Nathan Syvash ’25, who is from Ukraine, said that he grew up in the shadow of tense Russia-Ukraine relations, including Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the political unrest that followed.

“The TV was on 24/7,” he said, emphasizing how impactful long-simmering tensions have been for Ukrainians. “I was going to school and the TV was on. I was coming back home and the TV was on.”

Syvash also noted that Germany has partnered with Russia to build the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline. According to The New York Times, the pipeline would funnel natural gas from Russia to Germany, a project which President Joe Biden said on Feb. 7 would be stopped should Russia invade Ukraine.

In response to Russia’s increased military presence on the Ukrainian border, the U.S. has threatened economic sanctions, according to reporting by The New York Times.

According to Wohlforth, Russia could respond to sanctions from the West by reducing oil and natural gas shipments.

“If the United States attempts to sanction Russian petroleum exports, it would have really, really volatile effects on the markets — really dramatic increases in prices,” he said.

Somoff said that European reliance on Russian petroleum keeps many countries from “really opposing” Russia’s actions in Ukraine.

“When business interests conflict with their democratic values, European countries have a choice to make,” Somoff said.

Russian area studies major Ian Reinke ’22, whose thesis relates to Ukrainian language politics and rights, said he thinks that Russia’s ideal scenario would involve Ukraine “attached to Russia economically and politically.”

Rather than facing one “dictator” on its border, Ukraine now faces two — Russian President Vladimir Putin and Belorussian President Alexander Lukashenko — Somoff said.

After nationwide protests against Lukashenko in 2020, Putin “stepped in to save” the regime, Wohlforth said. He added that this event rendered Belarus “an absolute ally” to Russia.

Furthermore, Wohlforth said he believes China’s relationship with Russia also poses a “cause for worry.” He said that for the last 20 years, U.S. foreign policymakers have “feared” that China and Russia would form an alliance, which is what “appears to be happening” now.

“The two powers certainly agree on one principle: they do not like the U.S. offering security guarantees or intervening close to their borders,” Wohlforth said.

Somoff said that if Russia decides to invade Ukraine, Russia’s aggression could set a new precedent in international law that strong powers can annex parts of autonomous countries. Somoff said that the annexation of Crimea and war in Eastern Ukraine are “already a form of invasion,” adding that she is from a part of eastern Ukraine that is occupied by Russia and cannot visit her hometown as a result. She believes the best-case scenario for Ukrainians and Russians alike will be an end to Putin’s regime.

“Putin has lied many times, and he continues to lie about what happened in Crimea and what is happening in eastern Ukraine,” Somoff said. “He cannot be trusted.”

Both Somoff and Syvash said that the conflict in eastern Ukraine was not a civil war, but is the result of Russia’s “direct aggression,” according to Syvash.

Somoff explained that Russia has been attempting to aggravate the differences between eastern and western Ukraine by fueling tensions with “troops, money and weapons.” She added that despite “attitude differences” across the country, she predicts that pro-Russian factions in eastern Ukraine would not have escalated to violence without Russia’s involvement.

Wohlforth touted diplomatic solutions as the best possible outcome of the current tension between Russia and Ukraine.

“I believe that no one wants war,” Wohlforth said. “The challenge for statespeople is that there are some problems which can’t seem to get resolved to their satisfaction without at least the threat of force.”

Correction appended (Feb. 8, 2:10 p.m.): A previous version of this article referred to the Crimean peninsula of Ukraine, which Russian annexed in 2014, as “largely Russian-speaking and Russian-identifying.” According to Russian department chair Victoria Somoff, to whom the original statement was incorrectly attributed, large portions of the population of Crimea identify with Ukraine and the Crimean Tatars, a minority population, do not speak Russian as a native language. The reference has been removed.

Arizbeth Rojas ’25 is a managing editor of the 181st directorate from Dallas, TX. When she’s not listening to DJ Sabrina the Teenage DJ or planning her next half marathon, you can find her munching on a lox bagel.