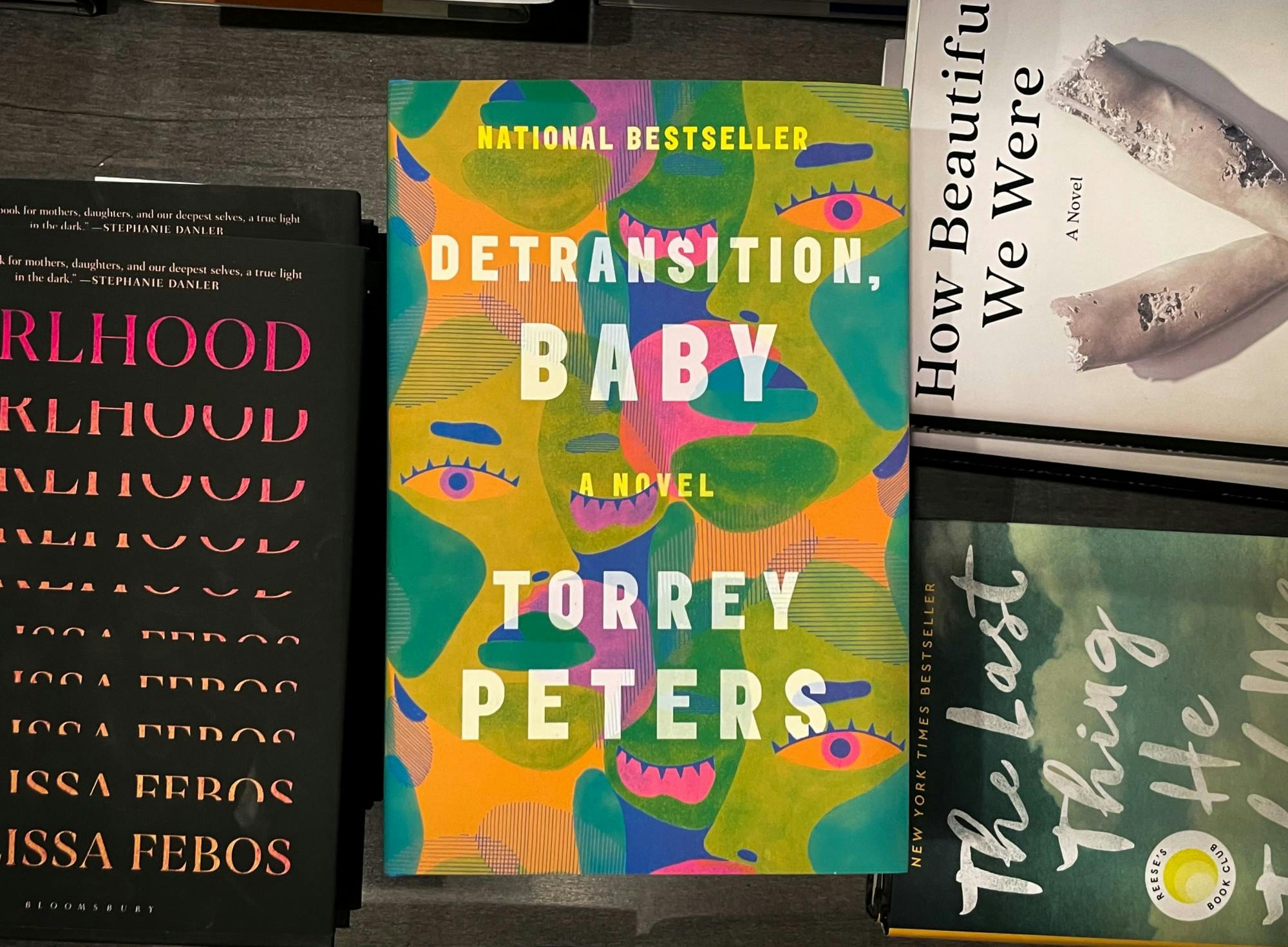

“Detransition, Baby,” Torrey Peters GR’13’s debut novel, has been making waves in the publishing industry. It was longlisted for The Women’s Prize and honored as a New York Times Editors Choice. Notably, it is one of the first novels by a transgender person to be published by a big five publishing house — in this case, One World, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

“Detransition, Baby” follows Reese, a transgender woman living in Brooklyn who, as she approaches middle age and tries to find meaning in her life, begins to think more about having a child. The chance to be a mother presents itself when Ames — Reese’s ex, who has detransitioned to a man and gotten his boss, Katrina, pregnant — suddenly asks if she wants to help raise the baby. The book follows their untraditional family through the complexities of womanhood, relationships, age, gender and sex.

A soapy, gossipy domestic novel with self-aware ties to the popular series “Sex and the City,” showrunners Joahn Rater and Tony Phelan have plans to adapt “Detransition, Baby” into a television show — with Peters writing the pilot episode and serving as an executive producer. The adaptation is not yet connected to a network and no release date has been set.

In an interview with The Dartmouth, Peters discussed her experience writing “Detransition, Baby,” her approach to the novel’s television adaptation and her perspective on diversity in the publishing industry.

What inspired “Detransition, Baby”?

TP: I was in my early thirties, and I was on the far side of transition. I was basically looking around for how people were making meaning in their life, especially women. There were a lot of cis women who I knew made meaning through work, through relationships, through making art, and especially through having families and becoming mothers. And my question began to be, well, what would that mean, for a trans woman? If this is how women make meaning in their thirties and in life, where do trans women fit into that? As I began to think about it, the novel sort of took shape.

Your book carries a great message with it, centering around a transgender woman in a context that we don’t often see in modern mainstream media. How would you say the current social climate and politics influence your writing?

TP: I have opinions about politics, but generally what I have, instead of specific opinions on specific issues, is a worldview. It’s the worldview that I apply to my novel on a longer timeline than individual news items, and that same worldview is what I apply to politics. There’s a shared analysis of how this stuff works in the sort of ethics of my fiction and the ethics that I bring to the world, but I try to make a hard line where I’m not necessarily bringing in the most recent legislation. I don’t bring that into the novels because it’s too reactive. I’m not going to let politics set the agenda for what I want to write.

In an interview with Rolling Stone, you mentioned that the soapy, domestic novel functions as a kind of “Trojan horse” for more political messages in “Detransition, Baby”. How do you see this “Trojan horse” working in the upcoming television adaptation of your novel?

TP: It’s not the same Trojan horse, but it’s still a Trojan horse. So, in this case, I think that I’m looking for the beats of comfortable television — the way that late at night, you turn on “Sex in the City,” “30 Rock” or one of these shows that has really comfortable beats. What you really want when you turn on one of these shows late at night is to just want to hang out with these characters. The Trojan horse here is that I want to create a show where the beats are comfortable, where you want to hang out with a character, and where it’s very satisfying to watch — but the people you’re hanging out with are trans women. I think that most people expect trans content to be sad, edgy or gritty. I think that one of the most subversive things you can do is make people comfortable hanging out with trans women and want to be friends with trans women without realizing exactly how and why that happened. The form does that work for you.

What do you hope that your readers and viewers take away from your novel, whether or not they directly relate to the characters?

TP: One of the things I hope is that they see commonalities across differences. I think that there are a lot of ways in which people read books by marginalized writers, whether those of writers of color, gay writers or trans writers. If they’re reading it to be educated about an “other,” somebody who’s not like them, it’s like, “Oh, I’ll read this book, and I’ll learn about trans women.” But when I read books by really great writers, I don’t learn about someone other than myself. I learn about myself if I read Toni Morrison. I learn about myself if I read James Baldwin. I learn about myself from Elena Ferrante.

I think that the trick of really good writing, the trick of empathy, is that instead of seeing it as an educational experience or an opportunity to learn about somebody else, it’s an opportunity to see yourself in somebody else. I think that’s a kind of emotional work that fiction does that almost no other category of writing or of art really does. You create an emotional closeness through fiction that’s unique.

“Detransition, Baby” is one of the first novels by a transgender woman to be published by a big five publishing house. How have you navigated the publishing industry as a transgender woman and what do you anticipate for the future of publishing?

TP: I think trans women are part of a larger reckoning in publishing, where it’s becoming more well known the ways that publishing has favored certain voices over others — especially voices of white men, historically — and I think we’re in a moment of correction. So you can say that there’s the question of how I individually navigated it. I started self-publishing, built up my own audience and brought my audience to publishing, to the larger presses, and I showed up with a bit of power that I developed outside the system. But I think one reason that was effective is that I was approaching publishing during a moment of larger reckoning for many different groups, trans women being one of them.

I think that the future of publishing isn’t just about giving contracts to diverse writers, but about fostering relationships within the company with those writers. So that when a trans writer, for instance, comes to a press, there’s somebody trans in that press who knows what that writer is talking about, and also knows when that writer is cutting corners or kind of saying some bullshit that otherwise they might get away with.

What advice would you give to aspiring authors who wish to tell stories that push boundaries in the publishing industry?

TP: It goes back to urgency. If you really have a story that feels like it needs to be told, you will find people who want to read it. More important than any sort of industry approval, or getting a book contract or any of those things, is finding those readers who really need to hear your story, and those people will do the work for you. That’s what happened in my case. My initial forays into the publishing world were met with rejection; people did not want to hear these stories.

What ended up happening is I went off on my own. I told the stories that felt urgent and I found readers. Three or four years later, the publishing industry was looking for other voices, and they heard that there was this trans woman who had an audience that they had no idea how to reach because I built that audience on my own. I think a lot of that is unique to my own case, but I also think it’s replicable for other people. If you don’t get institutional approval right away, that doesn’t mean your writing is bad, it means that the institution is wrong. So long as there are readers who are interested in what you’re saying, that institution will come around to you.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.