This editorial board has previously criticized the New Hampshire state government’s efforts to restrict student voting — and we remain concerned about how laws passed in 2017 and 2018 by Republicans in the state legislature can hinder students’ ability to vote.

But what stands out the most in this multiyear struggle over voter registration rules is confusion. In the run-up to the New Hampshire presidential primary, many Dartmouth students have been unsure if they can vote in Granite State.

The short answer is that yes, they can. But that answer has been hidden in what seems to be a deliberate pattern of vague answers and inconsistency on the part of New Hampshire’s government and some of its political leaders.

The law in question redefines the definition of “resident” and requires inhabitants of New Hampshire who both vote and drive in the state to register their vehicle in the state — since vehicle registration requires a trip to the DMV during work hours and registration fees that often exceed $300, opponents of the bill have decried it as a voter-suppression tactic.

The bill first appeared in 2017 as SB 3 and HB 372, then resurfaced in 2018 as the essentially identical HB 1264. Even at this point, members of the state government presented an inconsistent line. Governor Chris Sununu (R) first promised to veto the bill, claiming that he was “not a fan at all” of the nearly-identical HB 372. He then said he was hoping that “the legislature kills it.” When HB 1264 came on the table, Sunnunu maintained that his “position has not changed.” That comment was evidently disingenuous; a few months later, Sununu signed the bill.

Despite an ongoing series of court battles, the bill came into effect last July. But that has hardly made things clear, as state officials consistently declined to clarify what the law meant. Their only statement was a four-page memo with the appropriately garbled title: “Information on the legal definition of ‘resident’ for the purposes of determining rights, privileges, and responsibilities associated with being a New Hampshire ‘resident.’” It will probably come as no surprise that the memo did not answer the pressing questions on the requirement of vehicle licensing in order to vote.

In December, the state released further guidance on the law, but that guidance still left things unclear. It failed to address the big question: Can students who don’t own a car register to vote in the state? And what makes a student count as a “driver?” A recent NBC News article featured testimony from a Dartmouth student who now avoids the car-rental service Zipcar because the state failed to make clear whether the term “drivers” refers to car owners or to any students who drive.

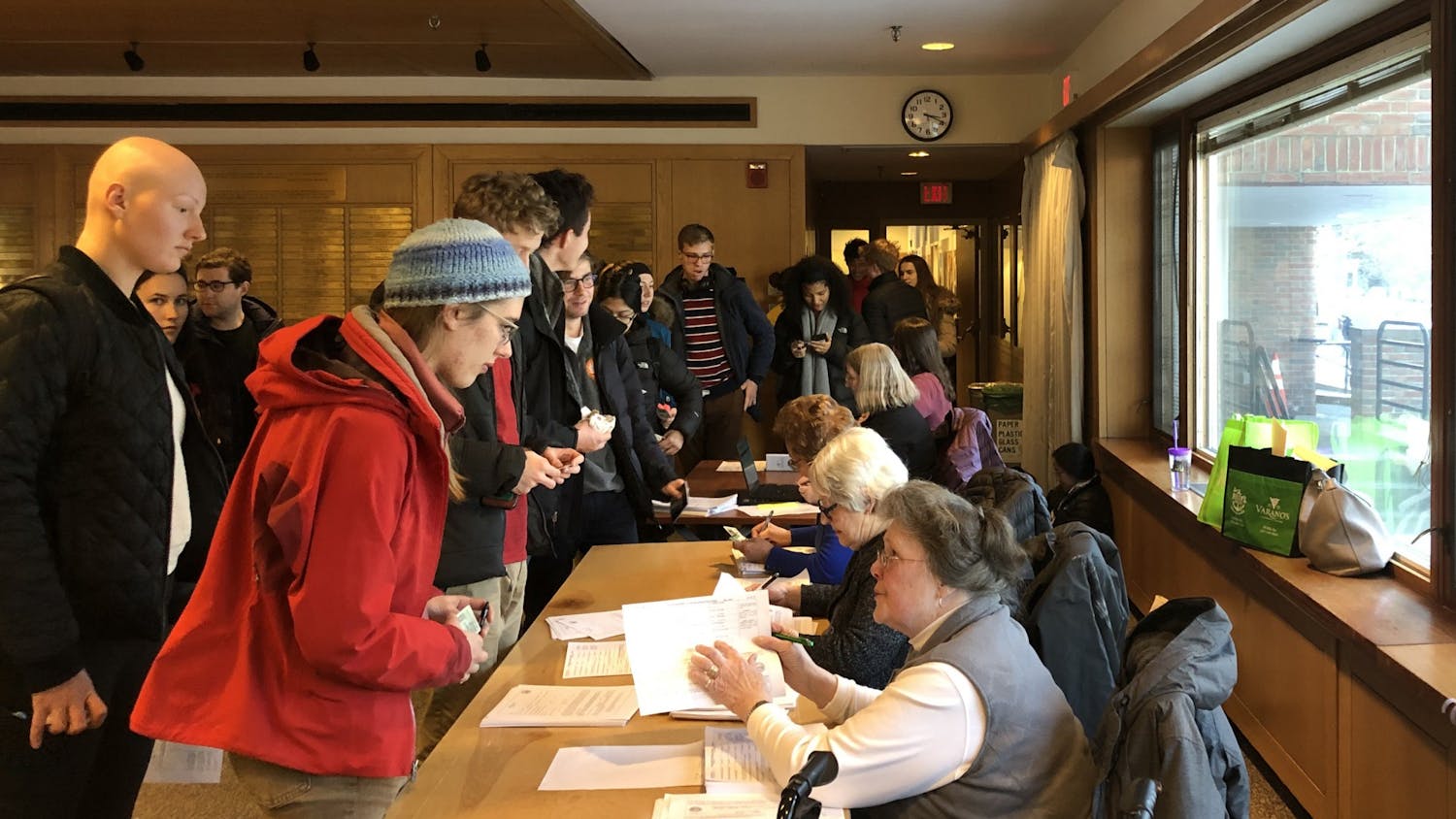

Let’s make it clear: Students at New Hampshire colleges are able to vote in the upcoming primary election. Whether you own a car or not, you currently have the right to vote in this state. But the constant lack of clarity on the part of the state government leaves many students here in doubt of that — doubt that could lead to the unfortunate result of decreased turnout among students.

One might hope that the troubling lack of clarity on behalf of the state government stems from a kind of ineptness. But given the original intent of the bill — to restrict students’ ability to vote — the continuous pattern of obscurantism and mixed messages gives the impression of a deliberate tactic to reduce student turnout.

The votes of students matter in New Hampshire, and it’s no secret that some people in this state don’t like that fact. We applaud efforts by campus groups to give students the information they need to get to the polls on Feb. 11. For their part, we urge state government officials to make their intentions clear: What does this law mean for student voting? Until New Hampshire students have a clear answer to that question, the state government has failed them.

The editorial board consists of the opinion editors, the executive editor and the editor-in-chief.