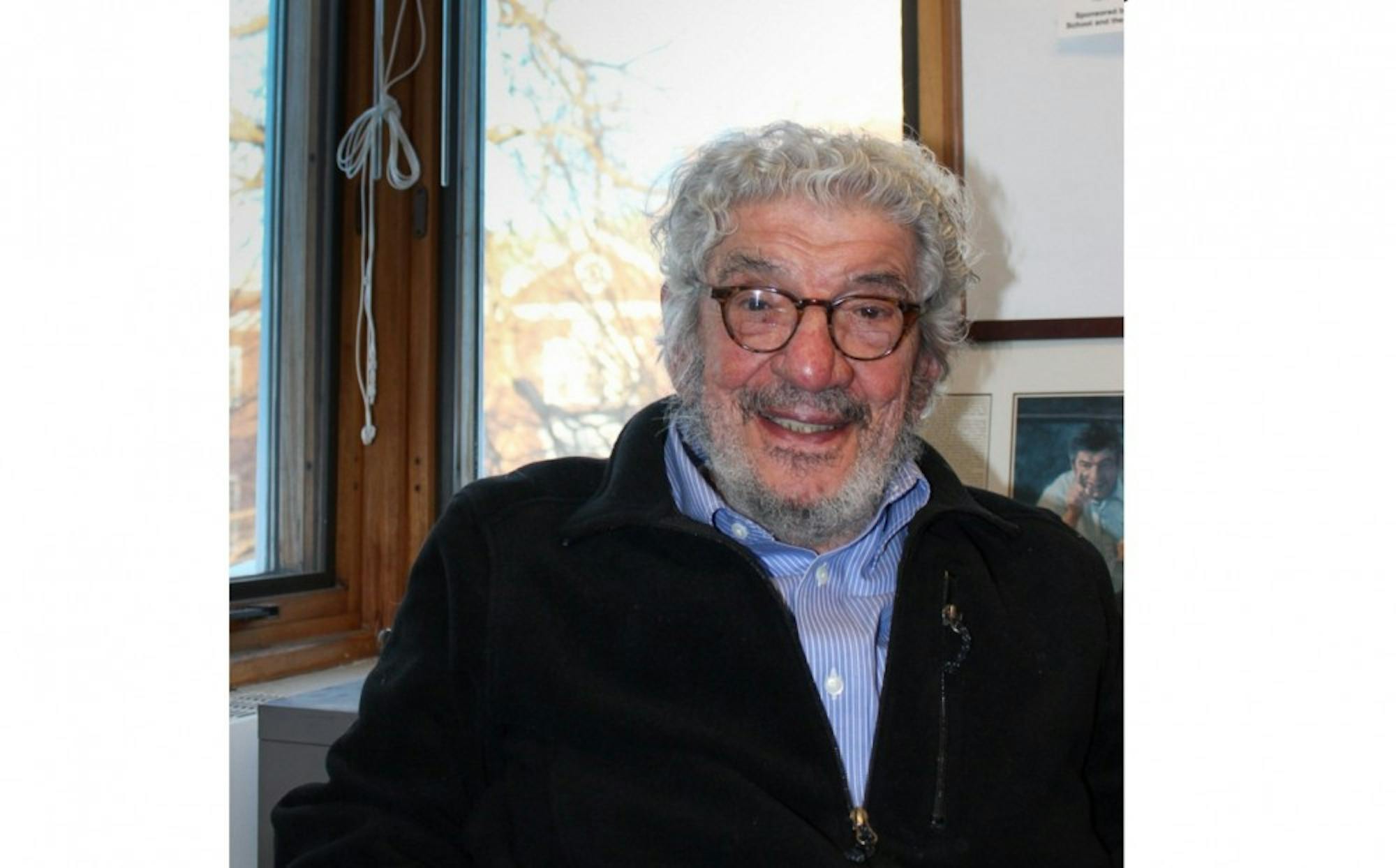

Following news of professor emeritus John Rassias’ death last week, friends, colleagues and former students took to social media to post memories and condolences. Beyond being a pioneer in the instruction of foreign languages, Rassias is remembered for his dedication to each individual student over his decades-long tenure as a professor.

“He was the very best of what Dartmouth offers,” former student Lara Nicole Dotson-Renta ’03 said, speaking about Rassias’ personal connection with all students and how he embodied the ideals of a liberal arts education.

Rassias developed his immersion-based, theatrical method for teaching foreign languages in the 1960s, which is used not only in all of the College’s introductory spoken language classes but also to teach thousands of Peace Corps members, language teachers and business leaders around the world.

He joined the Dartmouth faculty in 1965 and also founded the College’s language study abroad programs. He went on the serve as the director of foreign study programs for several years and continued teaching classes until 2012.

Worldfund director for the Inter-American Partnership for Education and Dartmouth Intercultural Education Specialist Jim Citron ’86 met Rassias in 1984 during a workshop Citron took to become a foreign language teaching assistant at the College, and since thenRassias has beena mentor to Citron.

Citron has worked with Rassias to developand run IAPE—a Clinton Global Initiative commitment created byLuanne Zurlo '87in 2007 as a partnership between the Rassias Center and Worldfund—for the past eight years and kept a close relationship with Rassias throughout his life, sharing meals and visits often in recent years.

When it came to students and teachers Rassias worked with, Citron said that Rassias always conveyed he believed in them, helping them feel they could overcome the difficulties of learning languages.

“His mantra was always that mistakes aren’t to be avoided,” Citron said. “Mistakes are just stepping stones to learning and to better communication and to creating an error-tolerant zone in a classroom where everyone’s free to explore and experiment. And if you get it wrong, it’s no big deal, and once you get it right, you get a big bear hug and you move on and you can celebrate a job well done.”

A Commitment to Teaching and His Students

Dotson-Renta said she still clearly remembers her first French theater class with Rassias.

“I couldn’t figure out where the professor was, then out he comes—you weren’t sure if he was above you, behind your or next to you. He was actually wearing a cape and climbing over the seats in the auditorium toward the stage while reciting lines from classic French theater, and he ends it by jumping up on stage with a big flourish and said, ‘Welcome to theater’ in French,” she said. “That passion for teaching and the element of surprise and teaching with heart and body inthat first introduction was very indicative of what knowing him was going to be like.”

Numerous former students shared stories of how he influenced their lives—academically, personally and professionally.

Rebecca Leffler ’04 said that Rassias is the reason she applied for the post-graduate James B. Reynolds scholarship for foreign study and spent nearly nine years in Paris. She said that the greatest thing he gave her was confidence, and that he had a way of making every person feel special and unique.

“John Rassias was truly a great man who made everyone he met feel that they too could become great,” she said. “He may be gone, but I still can hear his booming voice enthusiastically telling me, reminding me that there is still time to become great.”

Doston-Renta shared similar sentiments of how he inspired students.

“He had a way in which he would [make it] seem like your success was fated, it was in the stars—you just had to physically go out and get it but all the foundation was already there,” she said.

She recalled how during a term when she was having health issues and her mother came to visit, Rassias took them both to dinner to reassure her mother that she was performing well and had the support she needed.

More than a decade later she and her husband—who also studied under Rassias—still had a strong connection to Rassias, and he met their children last summer.

Kevin Jones ’83, a middle school teacher at the South Bronx, New York, charter school KIPP Academy, said that he remembers Rassias’ passion for life, people and culture, and that he tries to bring these attributes and Rassias’ understanding of how to reach students into his own classroom.

Jones said that having the experience of learning French through the Rassias method and ultimately traveling to France and becoming a drill instructor to teach other students affected the course of his life. He said that these experiences would not have been possible if he had not been exposed to Rassias and his passion for learning from other cultures.

Jones said he reconnected with Rassias in 2008, when he sent Rassias a clip of himself being interviewed on a French radio station.

“I really wanted him to know that all theseyears later this kid, who came from the Bronx and played basketball at Dartmouth and had done other things, had still kept connected to the method and was using it for good,” he said.

Rassias maintained this commitment to students all the way through the end of his career. Abbie Kouzmanoff ’15 and John Hammel Strauss ’15 both said they were lucky to be in the last class Rassiastaught—a French literature class with a focus on theater—their freshmen spring, because it allowed them to build relationships with him that lasted throughout their time at the College and after. They said Rassias made an effort to get a lunch with every one of his students during the term, and the three of them continued to have meals together once or twice a term until they graduated.

Kouzmanoff said that whenever they would be eating with him at Canoe Club, former students or community members would come up to the table and ask how he was, even students who had graduated more than a decade earlier.

Strauss said that at the dinners, Rassias would share detailed stories about former students, some of which went back 30 or 40 years.

“The amazing part about it was the absolute clarity with which he remembered the attributes and the mannerisms of each of these students, many of whom he remained in contact with until the day that he passed,” he said.

Both students said that Rassias challenged them to try new things and have novel experiences. For Kouzmanoff, this was the decision to travel to New Zealand her senior winter as part of the linguistics foreign study program, and for Strauss it was enrolling in an introductory Spanish class and ultimately studying abroad in Barcelona. Both also went to Paris their sophomore winter as part of the French foreign study program.

In addition to Rassias’ support, Strauss said his teaching methods enabled him to succeed as well, learning “the same amount of Spanish in three quarters of the Rassias method as four years of French in high school.”

Trevelyan Wing ’14 first encountered Rassias his freshman fall when Rassias spoke at his drill instructor orientation. Wing then took “French Theater Goes Greek” with Rassias his freshman spring and stayed in touch with him after. Wing said Rassias was always a mentor and friend.

Rassias was “always electric” and had “boundless energy,” Wing said.

“I remember him waving around a scimitar one day while reenacting a French play, and later he threw spaghetti at us in lecture,” he said. “It was all part of his method and it worked so well because no one ever complained of being bored in a Rassias-taught class. We were always on the edge of our seats.”

Rassias was able to change the world for the better with his “wonderfully creative and engaging” method for learning language, Wing said. He remembered Rassias would often say learning a new language is like adding a new color to one’s palette. Rassias encouraged Wing and other students’ love and pursuit of learning languages, Wing said.

“A lot of famous professors get caught up in their own affairs and forget about their students, but John was the opposite,” Wing said. “He was always reaching out to share advice, guide you along and just listen. He was really a teacher in the truest sense of the word, and he cared really deeply for his students.”

His Global Impact

Rassias’ global influence went beyond just founding the College’s language study abroad programs and serving as director of foreign study programs. The method he developed is used in numerous countries, including China, France, Japan, Greece, Turkey and Bulgaria.

His method has also been spread extensively through Mexico—IAPE has trained more than 2,000 public school English teachers in the Rassias method over the past eight years, and the program reaches 400,000 to 500,000 Mexican students per year, Citron said.

Rassias was actively involved with the program up until last summer, just before his 90th birthday, he said.

Valeria Alvarez, the academic coordinator of the English program for public schools in the Mexican state of Aguascalientes, said it is difficult to fully capture the impact that Rassias has had in Mexico. She first met Rassias in 2013 when she traveled to Hanover as part of the program, but said her relationship with him started in 2008 when Aguascalientes teachers were first sent to learn the method.

“When I started hearing about how somebody from another country was so worried about Mexican students learning English, I was doubtful. I thought there was a trick,” she said. “We’re not used to having people with such real and transparent feelings without any personal or economic interest behind it. He was really devoted to Mexican children having a better life.”

Alvarez said that the method is special not only because it helps the students, but because it makes the teachers become better people as well.

“When you’re teaching in an environment such as the one that we live in—crowded classrooms, hungry children and not enough physical space for everyone to be comfortable within the classroom—sometimes you start losing motivation and most of our teachers face that reality and they start losing that passion for teaching,” Alvarez said. “But once they learn to teach [with Rassias’ philosophy of] ‘heart by heart,’ that’s when the magic comes back.”

Julieta Zarco, an academic coordinator in Mexico City who attended one of Rassias’ programs last summer, also said that his “heart to heart” philosophy has helped both students and teachers in her area.

Cristina Malacara, an English teacher in Aguascalientes who also teaches the Rassias method to other instructors, said that meeting him and using his method has changed her life and her career.

Though Malacara had first met him several years ago on a group video call, she said she was still excited to meet him when she came to Hanover last summer as part of the IAPE Teachers’ Collaborative USA program.

“For me, it was like many girls’ Ricky Martin—he was my inspiration for so many years, actually meeting him was like meeting the author of your favorite book,” Malacara said. “When he crossed the door and I actually saw him and he was like in the pictures and videos that I saw before, it was amazing. I felt like I already loved him because he changed my life through the method.”

She said that to teach Rassias’ method, “you have to be a little bit like John,” and that is something she tries to communicate to other teachers—that they must embody his philosophy and reach students’ hearts.

While Malacara and many other teachers are mourning his death, she said Rassias’ transformation of the way foreign languages are taught will make him immortal.

“He is living through all the teachers he reached with his method—he left a little piece of him in us and we have the challenge, the huge challenge, to do the same with the rest of the teachers.”

Citron has found it heartening and empowering to see the outpouring of appreciation for Rassias from educators in Mexico.

“Part of the magic is he wasn’t afraid to express emotion, to convey to people that he really cared about them,” he said. “Getting teachers to realize that it’s not only okay but it’s a good thing to be interested in your students and care about your students. He used to push desks out of the way and say there should be nothing between the student and the teacher except love.”

When introducing Rassias at a 2011 conference, Citron said his magic came down to loving what he did and who he did it with, conveying to people that he believed in them, even when they did not believe in themselves, and being able to connect with people heart to heart across cultural barriers. Citron, along with many others, is determined to keep Rassias’ legacy alive.

“The best way to honor his memory is to keep doing as he taught us to do,” he said.

Rassias is survived by daughters Helene Rassias-Miles and Veronica Markwood and son Athos Rassias, as well as nine grandchildren.

Rassias’ funeral will be Dec. 11 at 11 a.m. in Rollins Chapel. A luncheon will follow at the Hanover Inn. There are calling hours on Dec. 10 from 6 to 8 p.m. at Rand Wilson Funeral Home in Hanover.

This article will be updated with more testimonials throughout the week. If you would like to share a memory, please email editor@thedartmouth.com.