Matt Parisi ’15, shortstop for Big Green baseball, lives the kind of life that makes you doubt everything you know about physics — like a magician pulling out an endless chain of handkerchiefs from under this sleeve. The difference between the two is that the magician waits with a prop up his sleeve. Parisi does not deceive.

Third baseman Nick Lombardi ’15 calls him a “renaissance man.”“He just knows how to do everything,” Lombardi said. “Say we’re talking about something random — action sports or something, like wakeboarding. He knows how to do it, knows something about it or will pick it up like that. He plays guitar. He surfs. You find new things out about him every day.”

Parisi makes room in his life where some students believe there is none, squeezing things like guitar, skateboarding and his now-defunct band into his rigidly structured athletic schedule, filling the sparse empty spaces with things that interest him.

Parisi shows up to team functions, catcher Matt MacDowell ’15 said, exactly on time or even a few minutes early because he operates on what MacDowell termed “Parisi time” — he’s never late but does not show up unnecessarily early either.

Anyone, Parisi said, can find some music they like on his iPod because his taste is “all over the place.” Yet there is something about the way Parisi goes about his interests that separates him from the pack — that turns the old adage “Jack of all trades but master of none” into a tag reserved for people who walk with a mentality of life that he does not share. He, MacDowell pointed out, does not stop until he is the master of as many trades as he can be.

“He’s what a baseball person would refer to as a total gamer,” head coach Bob Whalen said of Parisi. “I always admire and really respect him for the fact that he really wants to be good at everything he does, not just baseball, but he works at being good and he does that every day.”

Parisi is a unique combination of competitiveness and independence — traits he said he remembers learning from his parents.

His mother, a nuclear radiologist, is not as social as his father. She is focused, mostly, on her family and believes in the value of an independent child.

“She didn’t coddle me as a child,” Parisi said. “I made myself breakfast as a kid. She made me learn to motivate myself and not need her or other people to do it.”

If his personality can be drawn mostly from his mother, he said the other half can be drawn directly from his father. His father embodies competition, competing against his future wife’s brothers for much of their youths. The two families were close and have known each other for almost their entire lives. His maternal grandfather, Parisi said, used to hate playing baseball against his dad because the young player would always come up big in situations that demanded a clutch hit.

Before Parisi had even learned to walk, it seems that he knew what drove him. Many babies take their first steps to reach pleading parents with outstretched arms. The story in the Parisi household of Matt Parisi’s first steps, though, rings more true to his personality: there was a football across the room, and he wanted it, so he picked himself up and walked right over there to get it. And that, quite simply, was that.

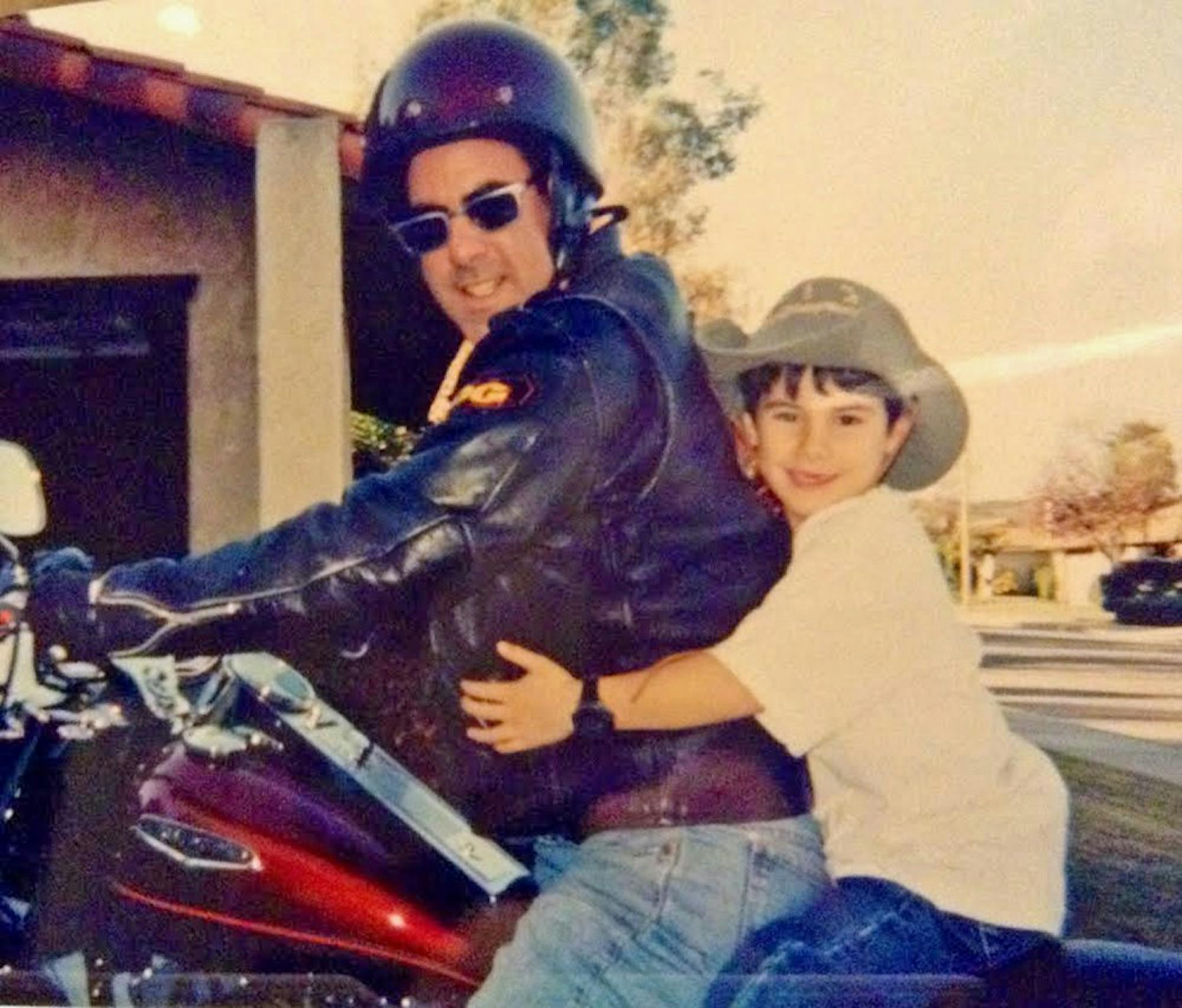

When he was a young child, Parisi wanted to be a cowboy — the pitter-patter of his sister’s and his feet pelted their childhood homes as they would run across the floors with hats and cap guns. His grandfather, though, thought he would be a veterinarian. His father, then a cargo pilot, used to bring home gifts for his son — often sets of toy animals, which his grandmother would supplement with Beanie Babies. To this day, he said, he enjoys watching nature shows on the Discovery Channel.

As he grew up in Florida — his family moved from Connecticut when he was six — he continued to play baseball, settling into the two positions he flirts with now as a college player, second base and shortstop. Eventually, his father was laid off during the recession, putting financial pressure on the family, which had big aspirations for both of its children. His sister is a recent graduate of the University of Florida and now works as a nurse in a neonatal intensive care unit.

With his exceptional grades in high school, Parisi was aiming high, but the cost of attendance at schools in the Ivy League can be a barrier — especially given that athletes are not allowed to receive athletic scholarships and must pay their own way or qualify for financial aid. As things became tighter and opportunities to visit family in California became more scarce, though, he said he never worried about his future.

“My parents were ready to sacrifice anything they had to for me to go to the best spot I could go to,” Parisi said, emphasizing the equal weight placed upon athletics and academics.

Parisi ultimately chose Dartmouth, settling into life in Hanover in the same way he always does — struggling, at first, to adjust to the academic demands of college and the new level of competition in collegiate baseball, but ultimately rising to the challenge.

“I had to learn my way through it by getting bad grades my freshman fall and winter and just adjust to the amount of work,” he said. “That’s basically it. One small step at a time.”

On the diamond, the adjustment was similar.

“It was a hard time for me,” Parisi said. “I really thought I was going to be a big impact coming in here, and I just never really had that role. I didn’t feel like a big part of the team at all, and being super competitive and dedicating my life to this work and wanting to help the team win and not being able to do anything about it was hard for me, mentally.”

He went into summer leagues, put in work and started his sophomore season at second base. He was named to the First Team All-Ivy that year, hitting .329.

“Without exaggeration, [Parisi] has the combination of being one of the most respected and most well-liked at the same time, which is not always easy to do,” Whalen said. “Great leaders have the ability to make everybody else better, and he has that.”

Academically, Parisi has taken all the introductory level earth sciences classes at the College — which have been his favorite — but decided that the major would have been difficult to balance with baseball as the department’s travel requirements would have kept him from practices and games with the team.

He is now finishing up his senior spring with upper-level government classes and said he spends his days tortured, in a half-comical, half serious sort of way, by the great questions in life — focusing not on the political aspects of the discipline but the moral and ethical questions that arise in theory classes: the limits of torture, the justification or lack of thereof for the use of the atomic bomb. He doesn’t enjoy making arguments and constructing his own theories, but instead prefers to listen to what people are saying and think about what it means.

“I’m very analytical,” he said. “I like to take in everything before I make a decision. I don’t want to jump into conclusions with anything. I like to make sure I cover all my bases.”

As Parisi entered his junior year and moved back over to shortstop — his preferred but not his “natural” position — he, along with the rest of the Dartmouth order, experienced an offensive dip. A preseason foot surgery left him off his game, and his confidence, he said, was lacking. He went into summer league and played “the worst baseball season” of his life, hitting right at the Mendoza line.

“I was failing at a rate I had never failed before,” Parisi said.

The penultimate game of the summer had been rained out, so he flipped through the television for a game to watch. His favorite team, the New York Yankees, were playing the Boston Red Sox, and a friend back home, Shane Greene, was pitching for the Yankees during Derek Jeter’s last season at Fenway Park — just a few hours away. A couple of texts and phone calls later, Parisi and a couple of summer league teammates found themselves with complimentary tickets to the game in Boston, which the Yankees won. Parisi reconnected with Greene at the hotel, spending the night hanging out with a guy he knew “like a big brother” as a kid and tasting, if only for a second, the life of a major leaguer.

“On the walk out of the hotel, still in my clothes from the night before while there were people lining up to get a look at the Yankees at they walked out, it almost felt like they were looking at me,” Parisi said. “On my walk to the train, I was thinking to myself, ‘This is what I want to do. This is the coolest experience I have ever had. I’m going to work my hardest to attain this.’ That night…after hardly any sleep, I ended up hitting the farthest home run of my life. It was over 400 feet.”

This season, Parisi has put himself in the position to potentially play baseball in the future, though, as Whalen pointed out, his future is partly out of his hands — scouts choose or pass over players for reasons that are often difficult to understand.

“Do I think he has the ability that is deserving or commensurate with guys who have gone into professional baseball? Absolutely,” Whalen said. “Whether he’ll get the chance or not, you can’t know.”

The thing about Parisi, now hitting .341 and anchoring the infield at shortstop, is that things — music, sports, school — are going well, but not because they always have and always will. They’re going well because when they’re not — or simply when he wants them to go better than they are — he moves, works, negotiates, listens and corrects until he can see that things are changing in a way that serves his goals.

Parisi is always competitive, but in the endearing kind of way — where he might be returning from a grueling several hours of practice to a quick team dinner before homework but still stop and acknowledge people by name with a smile. He doesn’t openly berate his teammates to win. He doesn’t overreact at the plate. He steps in the box, first with his right foot toeing the line, as if he’s thinking about the approach he will take with a focus that makes it seem like his entire future rests upon the success of that one at-bat. From surfing the waves in Florida to playing video games in his on-campus apartment that he shares with MacDowell, from writing songs to play on the guitar and bass with Lombardi to turning a double play on a diving catch, Parisi approaches life, in all its forms, with the same attitude:

“When you love the game and work as much as you do — as we do — then you want to be the best,” he said. “If you have a competitive spirit, then you want to be the best at whatever you do.”