Geduld outlined the ways in which the New Dance Group and other artistic movements used their performances as political statements during the Great Depression. The dancers followed instructions from Moscow while simultaneously responding to what they saw around them in the United States during the depression, according to Geduld.

"There was an exchange between the ideology being brought [from Moscow] and what they saw [in the United States]," Geduld said.

This political dance group contributed to new modernist forms of dance that broke existing stylistic norms, trading structure for an emphasis on personal expression. Jane Dudley, a choreographer and a leader in the New Dance Group during the Great Depression, wanted dancers to "create their own individual expressive movements," Geduld said.

Dancers utilized personal expression to respond to Great Depression politics and the New Deal. "Shock troupes" of dancers, for example, often sprung up to perform in public spaces to protest and raise awareness of social causes, Geduld said.

Performers in the New Dance Group eventually moved beyond their ties to the Communist Party by 1947 many of the group's dancers were performing on Broadway, but they "remained dedicated to social justice" in all they did, Geduld said.

Members of the New Dance Group were not immune to troubles during the Red Scare, when many citizens associated with Communism were persecuted in the United States. The group suffered because its members were often blacklisted, Geduld said.

"The New Dance Group dance groups were targeted specifically," Geduld said.

Former President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's New Deal policies also impacted the dance of the Great Depression, Geduld said. According to Geduld, Roosevelt's Works Progress Administration set up programs to foster the arts and to put Americans, including dancers, to work.

"The WPA dance unit both choreographed for musicals and did their own productions," Geduld said. They represented "a new American approach to art."

Performances by dancers Giannakis and Lofnes bookended Geduld's spoken presentation. Both performed the same dance "Time is Money," choreographed in 1934 and inspired by a poem by Sol Funaroff but did so individually, with Giannakis performing before the lecture and Lofnes performing after. Dudley originally choreographed the routine in response to the 1934 Garment Strike.

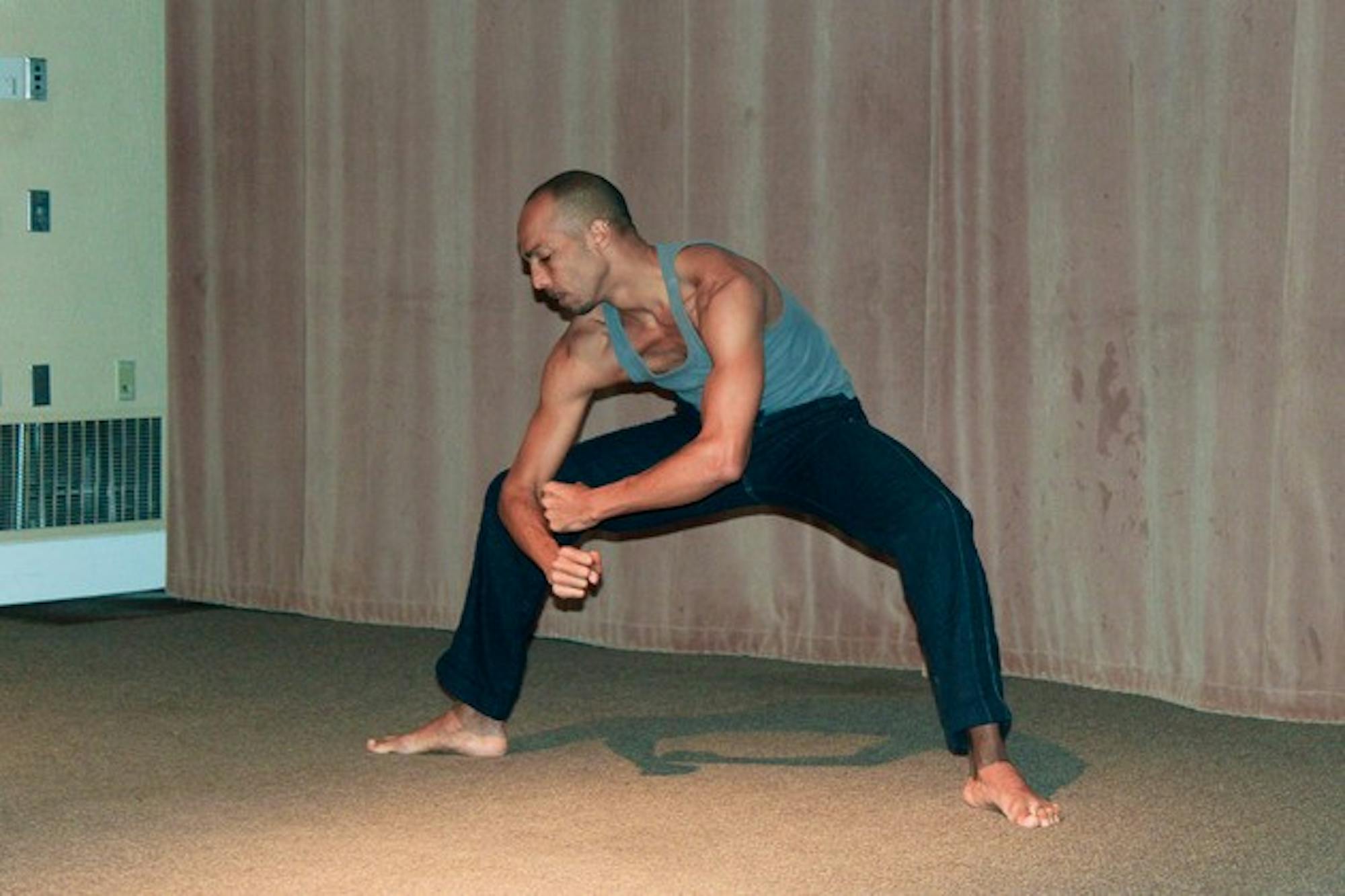

The dances were set not to music, but to a reading of Funaroff's poem, "Time is Money," which describes the struggles and exploitation of workers during the Great Depression. The dancers both literally acted out the poem's lyrics and otherwise relayed the poem's message through symbolic movements reflecting pain and hopelessness.

Everything about the dancers, from their facial expressions to their movements, evoked emotions of helplessness and desperation.

As Geduld read, "Our thin fingers ache with needles stitching pain," the dancers each moved their hands deliberately and mechanically, faster and faster until the work they appeared to be stitching escaped them and they collapsed to the ground, head in hands.

During each of their performances, Giannakis and Lofnes contorted their bodies and slowly walked forward, as if fighting an unbeatable obstacle. They lay on the ground and contorted their faces into a scream, seemingly in anguish or desperation. They each ran, grasping at things that were clearly out of their reach. Finally, they finished the dance facing the audience, slowly forming fists and assuming a new look of strength and defiance.

The lecture, held in Dartmouth Hall, was sponsored by the history department and the Fitness and Lifestyle Improvement Program at Dartmouth.