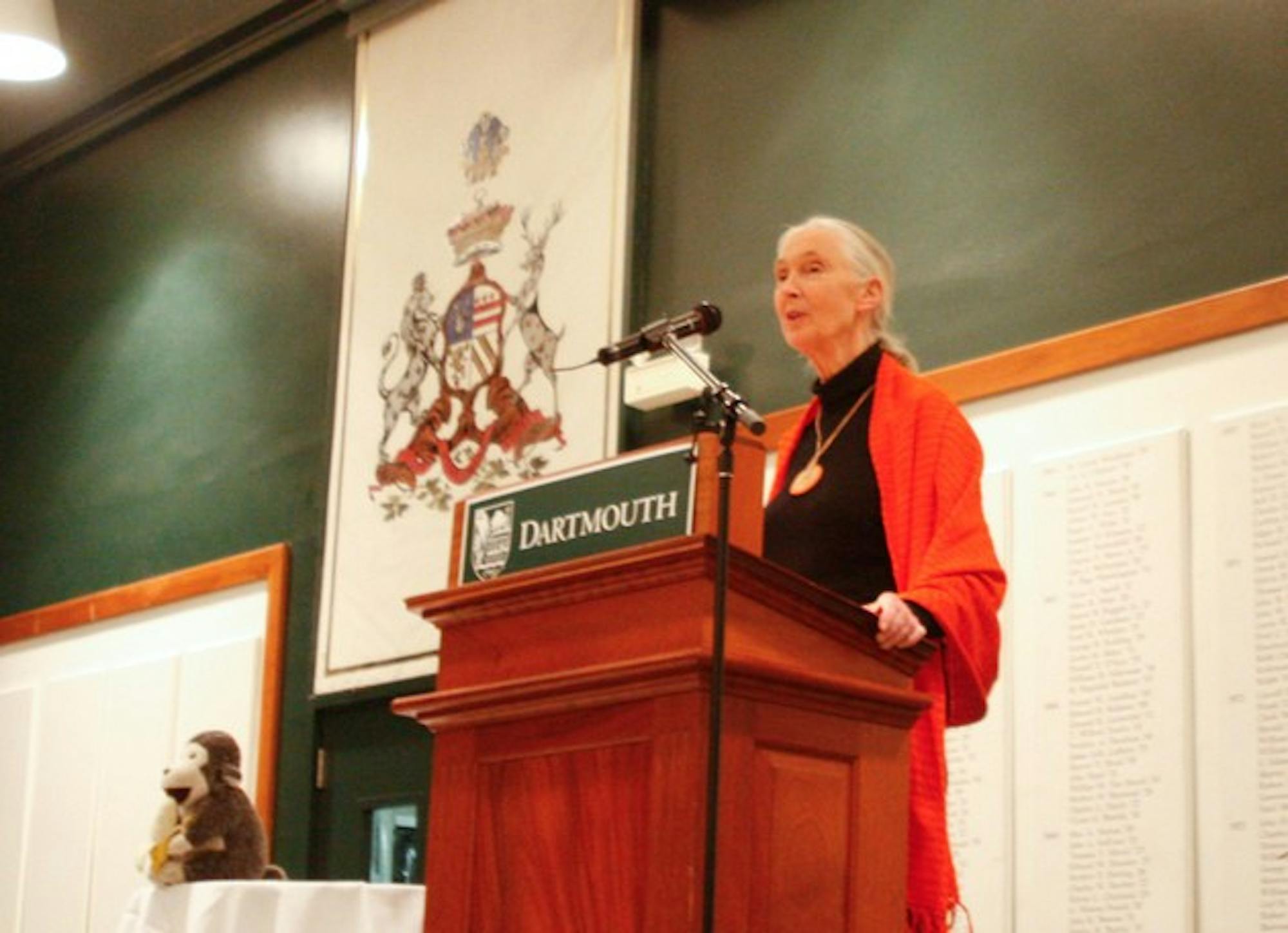

Goodall's speech, part of the Dickey Center for International Understanding's Great Issues lecture series and the College's Millennium Development Goals Week, was projected to audiences in four overflow rooms across campus.

Goodall -- who has seen the population of wild chimpanzees decrease from over one million in 1960, when she first went to work in Africa, to approximately 300,000 now -- told the story of a man who jumped over a barrier to save a drowning chimpanzee at the Detroit Zoo despite the risk of attack by the other chimps. When he looked into the eyes of the chimp, the rescuer said, it was like looking into the eyes of a man begging, "Won't anyone help me?"

"It's a look that when we see it and we feel it in our hearts, we have to jump in and help," Goodall said.

Goodall said the power of the human brain and the resiliency of nature allow her to remain hopeful even after seeing firsthand the detrimental effects of overpopulation, starvation, poverty, ethnic violence and globalization in Africa.

"If you think there's nothing we can do about it, that's wrong," she said.

She added that she is further inspired by the enthusiasm of young people. In 1991, Goodall started a youth community service program, Roots and Shoots, as part of the Jane Goodall Institute to inform and empower the world's youth to help people, animals and the environment, she said.

"I haven't met one problem where there wasn't a group of passionate people ... who were trying to make that problem right," Goodall said.

Members of the JGI hope to start a Roots and Shoots group to Dartmouth, John Trybus, Goodall's international tour coordinator, said in an interview with The Dartmouth before the speech.

Goodall also discussed the importance of motherhood as she highlighted the support she received from her own mother. Her late mother supported her dreams of going to Africa to study animals when everyone else laughed at her, Goodall said.

"Everything that I've done in life that I'm a little bit proud of, I can attribute to her," Goodall said.

When Goodall was hired by archaeologist Louis Leakey to study chimpanzees in Tanganyika -- the area that is now Tanzania -- the British government, who controlled the area, did not approve of the young British girl going into the African wilderness by herself. Goodall's mother left England to escort her daughter to the shores of Lake Tanganyika, Goodall said.

Good and bad mothers also exist within the chimpanzee world, according to Goodall. Offspring of the good mothers go on to be leaders and have more offspring than other chimps, Goodall said.

"The good mothers are protective but not overprotective," Goodall explained. "The bad mothers are much less protective and above all much less supportive."

Leakey sent Goodall to study the customs of chimpanzees, with whom humans share 98.6 percent of DNA, wondering if chimpanzee behavior might mirror how the earliest humans lived, according to Goodall. Goodall's breakthrough came when she saw the chimp David Greybeard -- Goodall named the chimpanzees instead of giving them numbers -- using grass and twigs to draw termites out of their mounds.

Until that point, it was thought that only humans used and made tools, Goodall said.

"Now we must redefine man, redefine tool or accept chimpanzees as humans," Leakey said in response to her discovery, according to Goodall.

After her initial research in Tanzania, Goodall, who had not gone to college, went to Cambridge University to earn her Ph.D, she said. Many scientists told Goodall that she had incorrectly collected her data because she named chimpanzees and observed that each chimp had emotions and an individual personality. At the time, most researchers thought that only humans had personalities, according to Goodall, but she had known since she was a child that animals had personality because of her personal relationship with her dog Rusty, she said.

Eventually, research with other animals corroborated her hypothesis that animals do more than just respond to stimuli, Goodall said, showing that the line that distinguishes people from animals is not as clear as humans once thought.

"It's a blurry line, and it's getting blurrier all the time," Goodall said.

Goodall's optimism, despite her exposure to distress, is inspiring, according to Bill Obenshain '62Tu'63, who started the endowment that funded Goodall's lecture.

"She crosses so many different issues, whether it's protection of species, whether it's climate change," Obenshain said. "These are all global issues."