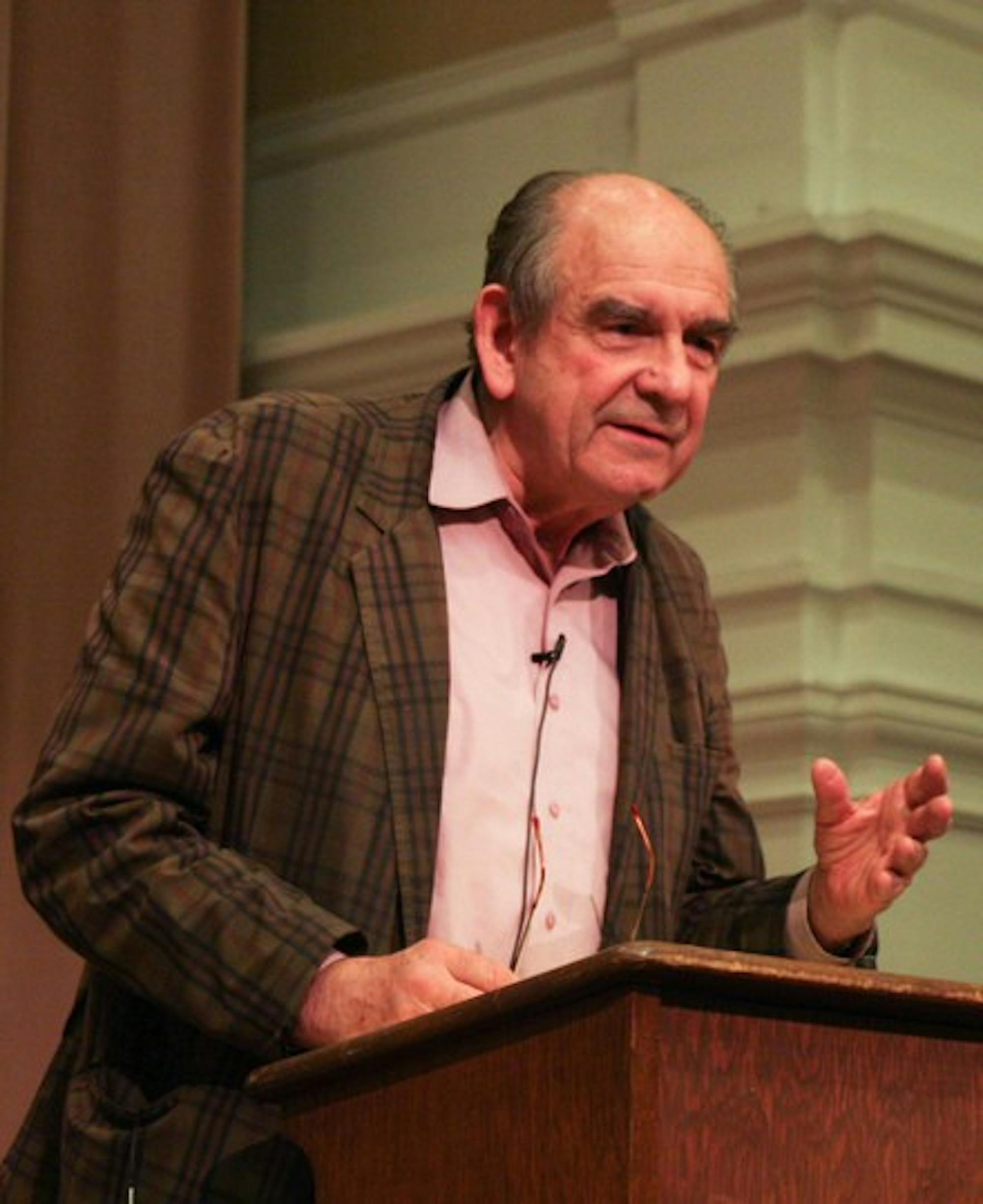

The lecture, sponsored by the Sphinx Foundation, coincides with the ongoing search for the College's next president, though Paul Killebrew '67, the foundation's director, said this was unintentional. The foundation, the nonprofit organization associated with the Sphinx senior society, scheduled the event shortly after College President James Wright announced his retirement last winter. The event was one in a series of lectures on the history of Dartmouth sponsored by the Sphinx Foundation.

"This lecture is quite timely because President Wright is stepping down and someone else will be taking over," Killebrew said

Daniell commented on the important role past presidents have had in shaping Dartmouth's history.

"There is no logic to Dartmouth," Daniell said. "You cannot understand Dartmouth without understanding the extraordinary sequence of individuals who held the presidency."

Daniell then explained that he groups the 16 presidents into four categories -- the family presidency, the ministerial presidency, the architectural presidency and the assignment presidency.

The first two presidents, the family presidency, tightly controlled the institution, Daniell said. He added that Eleazar Wheelock, president from 1769-1779, was the most calculating of the College's presidents, as Wheelock gave himself the right to choose his successor in the College charter. Wheelock forced his son John, class of 1771, to assume the presidency by tying John's inheritance to the College's wealth.

Daniell praised John Wheelock, president from 1779 to 1815, for raising money for the College, and noted that the original Dartmouth Hall and Dartmouth Medical School were built during John Wheelock's presidency. During his tenure, the College grew larger than Yale University, developed a very good regional reputation and graduated prominent alumni like Daniel Webster, Class of 1801, he said.

Daniell added that John Wheelock was not so popular with the College's Board of Trustees, as trustees were unhappy when Wheelock solicited the aid of the New Hampshire legislature during the Revolutionary War. This led the state to assume control over the College, a move disputed in the Supreme Court case, Dartmouth vs. Woodward.

"John Wheelock gets a lot of bad press because he was the bad guy in the Supreme Court case," Daniell said.

Daniell was ambivalent about the result of the Supreme Court case, which he said reestablished the College's independence but ushered in an era of ministerial presidents, whom he strongly criticized.

"The Wheelocks were not part of the orthodox, congregational way," he said. "Eleazar Wheelock was an evangelical, anti-establishment, anti-Yale minister, but the established orthodoxy took over as a result of the Dartmouth College Supreme Court case."

The ministerial presidents turned the College into a regional institution, emphasizing classical education and encouraging service and missionary work. Daniell noted that 95 percent of students at this time came from northern New England because the unprogressive, Congregationalist way was popular only in the region.

Presidential authority eroded during these presidencies, Daniell added. Two-thirds of faculty and students called for the resignation of Samuel Colcord Bartlett, Class of 1836 and president from 1877 to 1892, Daniell said, because Bartlett pushed faculty to be more religious and refused to raise money and expand the school.

The ministerial presidents were also unpopular for their political positions.

"Nathan Lord, for instance, had been an ardent defender of slavery and this would eventually cost him the presidency," Daniell said. "He voted against giving Abraham Lincoln an honorary degree after the Emancipation Proclamation."

The next four presidents, who formed the architectural presidency, turned Dartmouth into "the premier, undergraduate, liberal arts university in the country," Daniell said.

William Jewett Tucker, Class of 1871 and president from 1893 to 1909, modernized the curriculum and integrated the formerly separate Chandler Scientific School into the undergraduate college. Tucker also opened the Tuck School of Business as the first master business degree program in the nation.

John Sloan Dickey '29, president from 1945 to 1970, defended undergraduate education, Daniell said, by limiting the number of graduate students in the arts and sciences and ensuring that graduate students did not teach classes.

Dickey's promotion of undergraduate education has affected the college greatly, Daniell said.

"I taught over 5,000 students here at Dartmouth, and I graded every single one of their papers and sometimes their rewrites," Daniell said.

The last group of Dartmouth presidents -- John Kemeny, David McLaughlin '54Tu'55, James Freedman and Wright -- Daniell calls the assignment presidents, because each was hired to complete a specific goal. These presidents were the first selected based on criteria outlined by the Board of Trustees, he added.

The success of the assignment group demonstrates that the Dartmouth president does not need to have graduated from the College or have previous administrative experience, Daniell said. McLaughlin was a businessman and Dartmouth alumnus, while Freedman had been president of the University of Iowa but had no connections to Dartmouth prior to assuming the presidency.