Although I remained skeptical of Wenda Gu's lofty vision of a unified global "hair-itage," the documentary was about much more than just the Dartmouth installation, offering telling glimpses of the state of art in China and a lasting collaboration between two friends.

The Dartmouth: So how did this project get started?

Ward: I started the project before [I went to] Shanghai, in collaboration with the Hood Museum. I took five or so hours of footage of the Dartmouth installation events on campus, including the hair donations. [Ward went on to shoot 50 more in Shanghai]. I was asked to be the videographer for the project for the year.

The D: What was the film's concept?

Ward: The original focus of the movie, as conceived by the Hood, was on the Dartmouth and Upper Valley community participation in the creation of the installation. The kind of questions they were asking for the film were, "What does your hair mean to you?" A guy from NHPR [New Hampshire Public Radio] came with us to collect hair donations from the Upper Valley salons, and he was asking questions like that. In a way, I thought his questions were off, as if he didn't care for the vision or reach of the installation project. He finally asked, "Do you color you hair?" to the people involved. I thought, we need the other side of the project -- the creation and assembly in Shanghai -- to show its proportions and meanings.

The D: How did Westheim get involved?

Ward: I like the way he thinks and I'm always up to discussing things that I'm feeling with Westheim. I needed someone with a critical eye and mind like that to complement the visual images, all the possible meanings of the shot. Westheim really saw ... [to Westheim] What did you see? He just knows things...

Westheim: So we ended up writing the grant together.

Ward: We had to frame it as a research project, not an art project.

Westheim: We took some books and we looked at possible angles that we could [use to] approach this, and we were kind of expecting that Wenda Gu would be a major part of it. He's very separated from the Chinese art scene as a whole; he's only recently moved back to Shanghai. What's going on [in China] is this new way of dealing with industrial growth and business growth, so we saw the art scene expanding as a result of these art objects being pushed as "commercial projects" everywhere. There are several artists of some note, but a lot of the things we saw were of Western/Eastern art, things that looked very trendy, appealing at a first glance, but really when we get down to it, not doing anything original. Shanghai has a very commercial scene... a pop art scene.

Ward: One gallery curator said it's a shame that traditional Chinese art continues to be copy and imitation.

The D: So is that what Wenda Gu is doing?

Ward: He's doing something completely different entirely because he doesn't identify as a Chinese artist.

Westheim: He has a certain vision of how humans are developing. It's very disillusioned in a different way, how we're all moving towards a biological millennium, which means that mankind is changing because of the advent of climate change, and genetic engineering...

Ward: And new species...

Westheim: When you go to a city like Shanghai, people can't really get a grasp on what's going on, or see how it all fits together as a society. [Ward]'s brother had been working on a book project while we were there. He has been traveling in Asia for a year, so he showed up and was very aggressive with his questions, but he got people to answer the questions. He added another impression because he got at why people were changing and this new place that people were changing for themselves. It gave us a perspective on...

Ward: The back alleys, the barges, the dark areas, propaganda art.

The D: What was Wenda Gu's part in all of this?

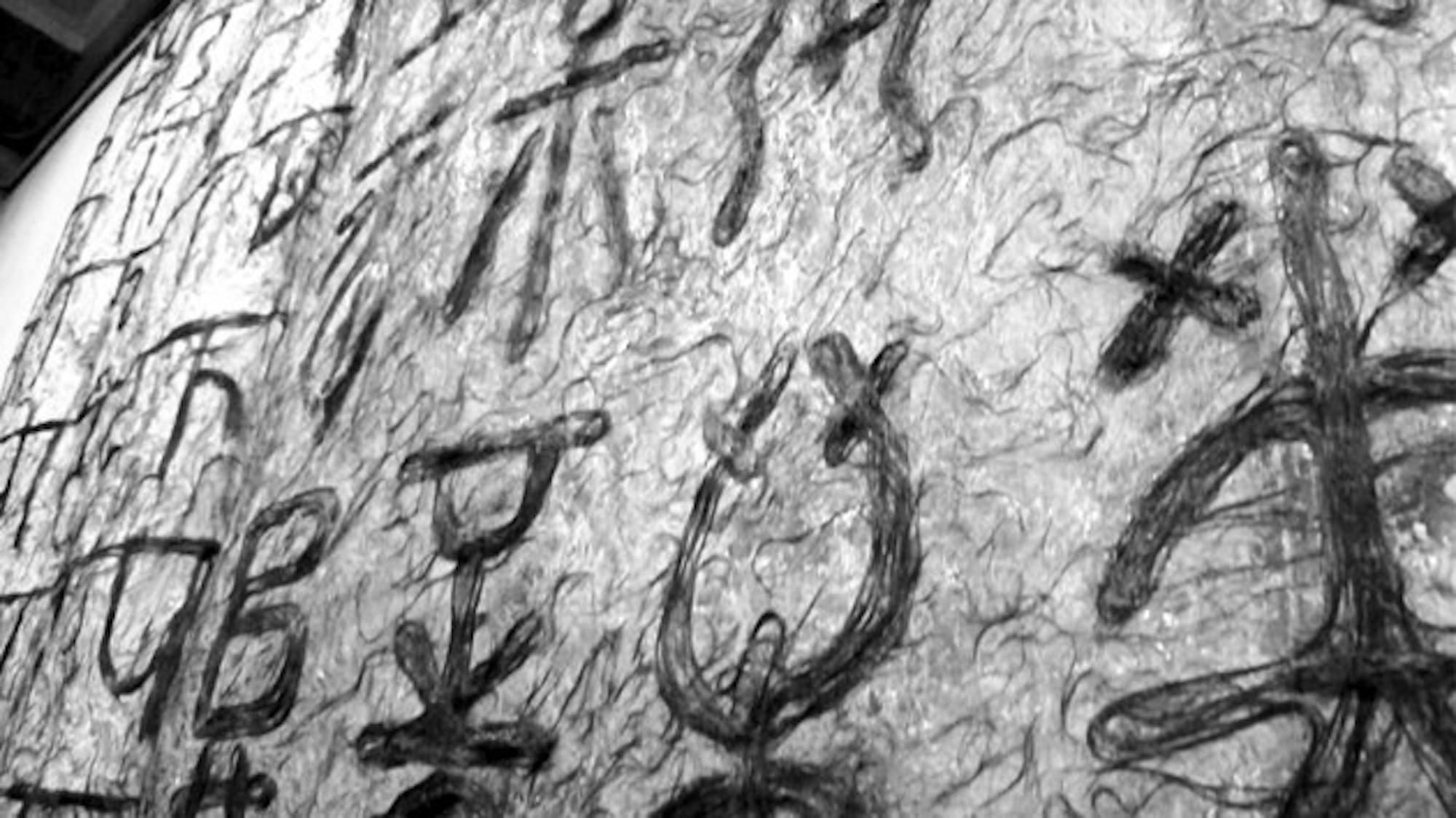

Westheim: He has this studio in Moganshan Lu and has four women who work for him and braid the hair and do the projects. He basically designs a lot of these [installations] on the computer and is active in the design process and the women sort of create the projects out of the hair.

Ward: He gets [art director] Wang Jing, and he sends her these models and plans and so all of the hair was shipped from Dartmouth to his studio in Shanghai, so basically what is used is Elmer's glue and hair.

The D: Around how much time did you spend with Gu?

Ward: We worked with his art director, asking for contacts of traditional Chinese artists, and then she would set up these interviews for us. Xu Gan, a good friend of his, and my father's friend David Chen, the V.P. of GM China, kind of became our godfathers there, setting up our contacts.

The D: Do you think the film turned out very different from what you had expected?

Ward: So much of the story lay outside of the studio and with these other perspectives, we had to gauge it. The time that we spent with Wenda Gu was very formal. He'd just say, "I'll give you 15 minutes." And he set us up with Pearl Lam, who lived on the top floor of this apartment building that she owns, the penthouse which is just for parties, all just contemporary art. The first thing you see [when you walk in] is a psychedelic movie of yourself and a Turkish butler and a hundred dollar glass of champagne and a bowl made of glass-blown penises. All the patrons of the arts were all there socializing, and we were given 15 minutes.

Westheim: It was a pretty ridiculous situation.

The D: What's next for you two? Would you work together again?

Ward: I'd love to work with Jared, I think we complement each other, how he thinks and how I feel...

Westheim: You feel for me? [laughs]

Ward: Yeah, so how does it feel for you, Jared, working on a documentary for the first time?

Westheim: It was good ... I definitely learned a lot.

Gu's installation will be finished before the end of the term, ready for the exhibit's opening on June 6. The documentary will be viewable in the Hood, but details are not et set. The Hood will also host an exhibit of Gu's work to accompany the installation in Baker-Berry, entitled "Retranslating and Rewriting Tang Dynasty Poetry." The artist's "united nations" project has been ongoing since 1993, in a myriad of countries around the world.

![HONEYJOON_[Ines Gowland]_4.PNG](https://snworksceo.imgix.net/drt/7af2efc8-1bd1-4001-b754-e2718ce663b8.sized-1000x1000.PNG?w=1500&ar=16%3A9&fit=crop&crop=faces&facepad=3&auto=format)