Our generation learned to share in kindergarten, but along the way, the word's meaning was swallowed whole by the digital age and the expectations for our interpersonal interactions came to mean more about generating "likes" than waiting our turn on the playground. In the latest of Facebook's highly publicized design changes, CEO Mark Zuckerberg announced that the social media giant would aim to function as a "personalized newspaper," allowing for theoretically endless information sharing and streamlining content according to personal preferences.

As many fear that print journalism is dwindling into its twilight years, digital sharing resources like Twitter and Tumblr are coming into their own, no longer simply receptacles for inside jokes and pictures of cats in Christmas sweaters. During spring break, the selection of a new Pope was simplified down for worldwide consumption to a succinct #whitesmoke. Sharing information instantaneously via social media is a hallmark of the 21st century, and in few places is it more common than amongst the aspiring intellectuals of a college campus. We're not always sharing Pulitzer Prize-winning essays, but we're almost always sharing something. The Mirror wanted to know more we surveyed Dartmouth students on their means and motivations for spreading information via social media to get a more numerical handle on the role of digital information sharing in our community.

The Internet has not always been like this. When we joined Facebook in middle and high school, we used it to connect with friends and family, posting embarrassing jumping pictures in front of statues in Washington, D.C., and snapshots taken in shopping mall mirrors. The Facebook status bar came with pre-set options so we could let our dearest know we were "at a party" or "doing homework." The greatest level of decision making came from people trying to circumvent the mandatory inclusion of "is" in their updates.

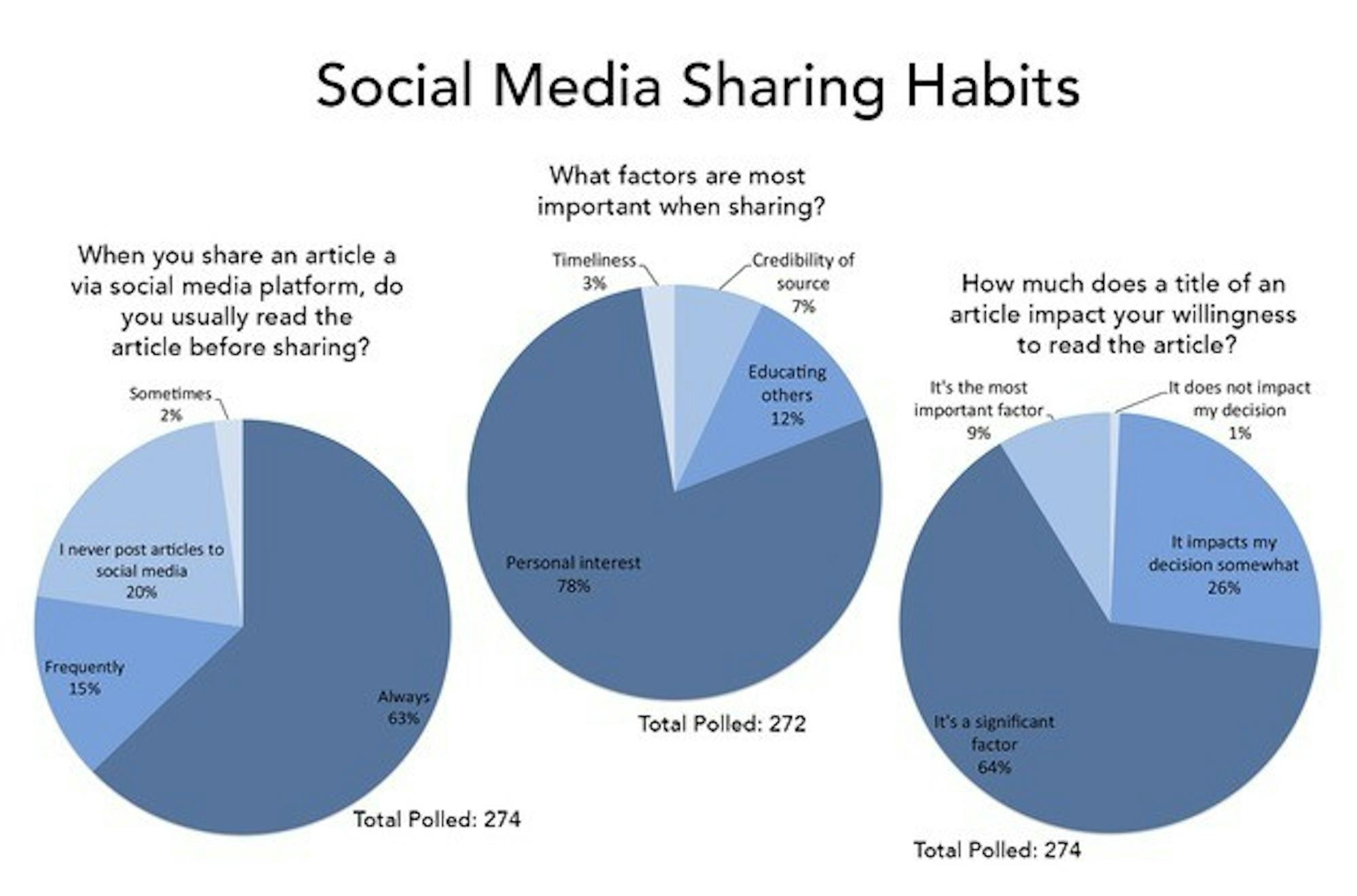

Recently, however, social media sites like Facebook and Twitter have transformed into vehicles for sharing news stories. Anyone with access to the Internet can tell you that people often post articles, YouTube videos and other websites as their statuses, sometimes including a pithy comment or observation. If you want to get information to someone else? Share it on their wall. Tweet at their handle. . Links to share articles are on every major news websites, and the ability to tell people what you're currently reading is everywhere. In fact, only 20 percent of Dartmouth students surveyed said they never shared articles via social media.

Have Twitter and Facebook become our first stop for news? The deaths of Osama bin Laden and Whitney Houston and the emergence of the Arab Spring are all recent examples of the power of the Internet's immediacy. Of course, it's not always breaking news that we're probing. In medical ethics, scientists often ask themselves if they are working toward a new innovation because it's necessary or simply because they can. What would we see if we asked this same question of the proliferation of websites and links? What is the world getting from the fact that "Kanye West Wing" not only exists but can be sent, in the form of a single line, from one computer to another in less than a second?

While 2012 data is not yet finalized, Facebook released the top 40 shared articles in 2011 to the public. Satellite images from before and after the Japan tsunami from The New York Times topped the list. In second place, CNN published an opinion piece from American Teacher of the Year Ron Clark on what teachers really want to say to parents, and in third, CNN once again claimed glory with a piece calming fears over changing zodiac signs. Clearly, the list reflects a diversity of concerns and interests amongst Facebook's user base.

Maybe we should all simply revel in excitement over how far we've come, from the days of news being the privilege of the elite to mass consumption of information at breakneck speeds. But new forms of media aren't without problems. Titles have become essential to generating attention for articles. 64 percent of students surveyed said the title of an article significantly impacted their decision on whether to click a link and peruse the content. With increasing availability of information has come a dwindling attention span and an increased need for sensationalism to generate page views.

With the demanding pressures of news cycles, breaking stories published within seconds may face accuracy issues. Celebrity deaths, the news of Facebook shutting down or changing its policies and fake kidnappings are all stories that have spread and turned out to be false. In a December op-ed in The Times, former executive editor Bill Keller opined that the closure of many foreign bureaus could mean a sacrifice of accurate and immediate coverage. He drew a connection between President Barack Obama's incorrect classification of Libyan Ambassador Chris Stevens's death as a protest that exploded into violence and similarly flawed coverage in many major news outlets. While the issues faced here at Dartmouth are usually more within arm's reach, Keller has a point in the impact of journalism on public perception, and the way in which the content articles we so eagerly share influence what our friends and family think of the major stories of the day.

It is also essential to review the validity of the article's source before posting or commenting, especially when we have so many to choose from. Only 7 percent of students said the credibility of a source was most important factor in choosing when to share an article. 63 percent said they always read the entire article before sharing to social media, but a thorough reading doesn't guarantee accuracy. The blog "Literally Unbelievable" documents people who post articles from The Onion believing them to be true. In a notable example, a man posted the satirical article entitled "Punxsutawney Phil Beheaded For Inaccurate Prediction On Annual Groundhog Slaughtering Day" with the caption "Cruel and unnecessary. I don't care if it is tradition." Although the poster wished to advocate animal rights, his failure to realize the humor behind the headline made him something of a laughingstock. And it's not just The Onion The New Yorker's "The Borowitz Report" publishes satirical articles that are often mistaken for reality. This week, a headline poked fun at Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia and the court's consideration of same-sex marriage, reading, "Scalia Furious He Has To Hear About Gay Couples All Week."

Maybe nothing has truly changed. Accuracy and objectivity have always been dynamic issues in journalism. Overall, we at the Mirror are excited to know that people are reading and sharing the things that interest them. From Perez Hilton to New York Magazine to The Daily Beast, the increased popularity of sharing and online news could just mean there's media to suit all types and tastes. Dartmouth students seemed to think so 78 percent of those surveyed said that personal interest was the biggest factor when choosing an article to share with their online friends. Those most eager to share might be disappointed to know that only 15 percent said they always read the articles their friends send to them, but imagine how few would read it if it weren't available with the click of a finger.

It would be far from ground-breaking to say that today's college students have grown up on the Internet. Our class information, our entertainment and all of our closest friends exist simultaneously in the real world and within the boundaries of a computer screen. Parents who once cut clippings for their children can now send them via email. We now share everything we think, or at least everything we think is interesting remember, retweets do not equal endorsement. Our Internet presence says a lot about us, in a way that is both visibly obvious and increasingly immediate. Maybe we'd do best to embrace it and click "share" if we dare.