“Warm-cut through Blobby @now. Bring a fracket.”

Unless you’re a student at Dartmouth, you probably have no idea what I just said. First of all, what is a warm-cut, and where is Blobby? And second, why didn’t I just say it in normal English?

For the average Dartmouth student, school-specific lingo is so engrained in our everyday vocabulary that we barely notice when we’re “speaking Dartmouth.” Words like “Foco,” “facetimey,” “blitz” and “flair” are essential to how we communicate with each other, and for many students, these words create a valuable sense of community.

When they arrived on campus this fall, Skylar Miklus ’22 quickly embraced campus slang. After reading The Dartmouth’s guide to Dartmouth lingo, they adopted vocabulary such as “@now,” “FFB” and “flitz.”

“Especially coming as a fall semester freshman, you kind of feel like you’re automatically part of something, like you’re in some secret club by knowing how to speak Dartmouth,” Miklus said.

Lara Balick ’19 agrees that Dartmouth lingo “builds community and makes people feel more connected to the school.”

According to linguistics professor Thomas Ernst, slang words develop for this very reason. He explained that “one of the biggest functions of slang for any group, particularly colleges, is that once you know the local slang, you’re sort of implicitly saying, ‘We’re part of the same group, and other people aren’t.’ It bonds you together.”

Miklus was on to something when they said that speaking Dartmouth slang felt like initiation into a “secret club.” As University of North Carolina Professor Connie Eble writes, “Slang can serve to include and slang can serve to exclude. Knowing and keeping up with constantly changing in-group vocabulary is often an unstated requirement of group membership...”

Especially at an insulated college like Dartmouth, it makes sense that slang is used to create a sense of in-group identity. But Eble also notes that slang words are “ephemeral,” meaning they regularly fall out of use and make way for new words.

I asked Ernst what he considered the average lifetime of a slang word. He said that most slang survives no more 20 or 30 years, although there are some words that can hang around for much longer. At Dartmouth, words like “facetimey” or “flitz” will probably be more short-lived, since they feel trendy and need to be passed on from one class to the next. On the other hand, names for places like “the Hop” are more likely to catch on with outsiders, so they could stick around for generations.

Seniors Madeline Omrod ’19 and Balick said that in their time at Dartmouth, they haven’t noticed much change in campus slang. But when I asked Kiera Grimes ’12 about slang during her era, it turns out that some changes have occurred in recent years.

Grimes prides herself on her use of “abbrevs,” and she was able to list many words that circulated when she was at Dartmouth. Most of the lingo she used remains popular today, including words like “the Stacks,” “warm-cut” and “trippees.”

Other words that Grimes mentioned, however, sounded completely foreign to me, including the term “blitz-jack.” Apparently, a blitz-jack was “when you left your blitz up at a blitz terminal and somebody would go in and write some crazy email from your email address and then send it out to the school.” In order to understand this word, I had to ask Grimes what a “blitz terminal” was. Grimes explained that while nowadays every student has a personal laptop, back in the early 2000s, Dartmouth students had to line up after meals to check their blitz (or email) on devices called “blitz terminals.”

It’s not hard to see why the word “blitz-jack” has fallen out of use. With changing technology, it is no longer easy to hack into someone’s email and spam the entire school. But other words have faded away for reasons less obvious. For example, Grimes and her friends often used the term “OTM,” which stands for “on the move,” when they were moving from house to house on frat row.

Ernst explained that sometimes, slang words disappear once they start to sound outdated. Since slang is so deeply tied to group identity, “as the group gets older and older, you either lose that identity, or college kids go off to other places, or it starts sounding ridiculous to the younger generation and you stop.” Ernst specifically mentioned the word “groovy.” Popular in the 1960s, by the late 1970s and early 1980s, “groovy” started to sound absurd to the younger generation of Americans, and it was soon used only ironically.

This phenomenon might explain why “OTM” has faded from the Dartmouth lexicon. It failed to catch on with the next generation, and new words appeared to take its place. Meanwhile, we’ve come up with new abbreviations that Grimes’ generation never used, such as “Blobby” for “Baker Lobby.”

Changes in slang can reflect shifts in culture, for better or for worse. For example, Grimes didn’t recognize the term “snakey,” despite how often it is used nowadays. It was hard for me to pinpoint exactly what this words means, but Miklus put it simply: “Snakey? Like an econ major.”

The fact that “snakey” only recently entered “Dartmouth speak” might indicate that Dartmouth is becoming, for lack of a better word, “snakier.” Given the connotations of “snakey,” we could consider this a negative change in our school culture, though it would be difficult to track when and how the shift occurred.

On the other hand, Grimes was disappointed to learn that “the Dartmouth X” is still discussed on campus.

“I feel like some things about Dartmouth will unfortunately never change or have not yet changed,” she commented. Miklus also said that of all the Dartmouth lingo, they wish “the Dartmouth X” would disappear. Presumably, if Dartmouth erases harmful social constructs like the “X,” then such words will naturally drop out of our vocabulary.

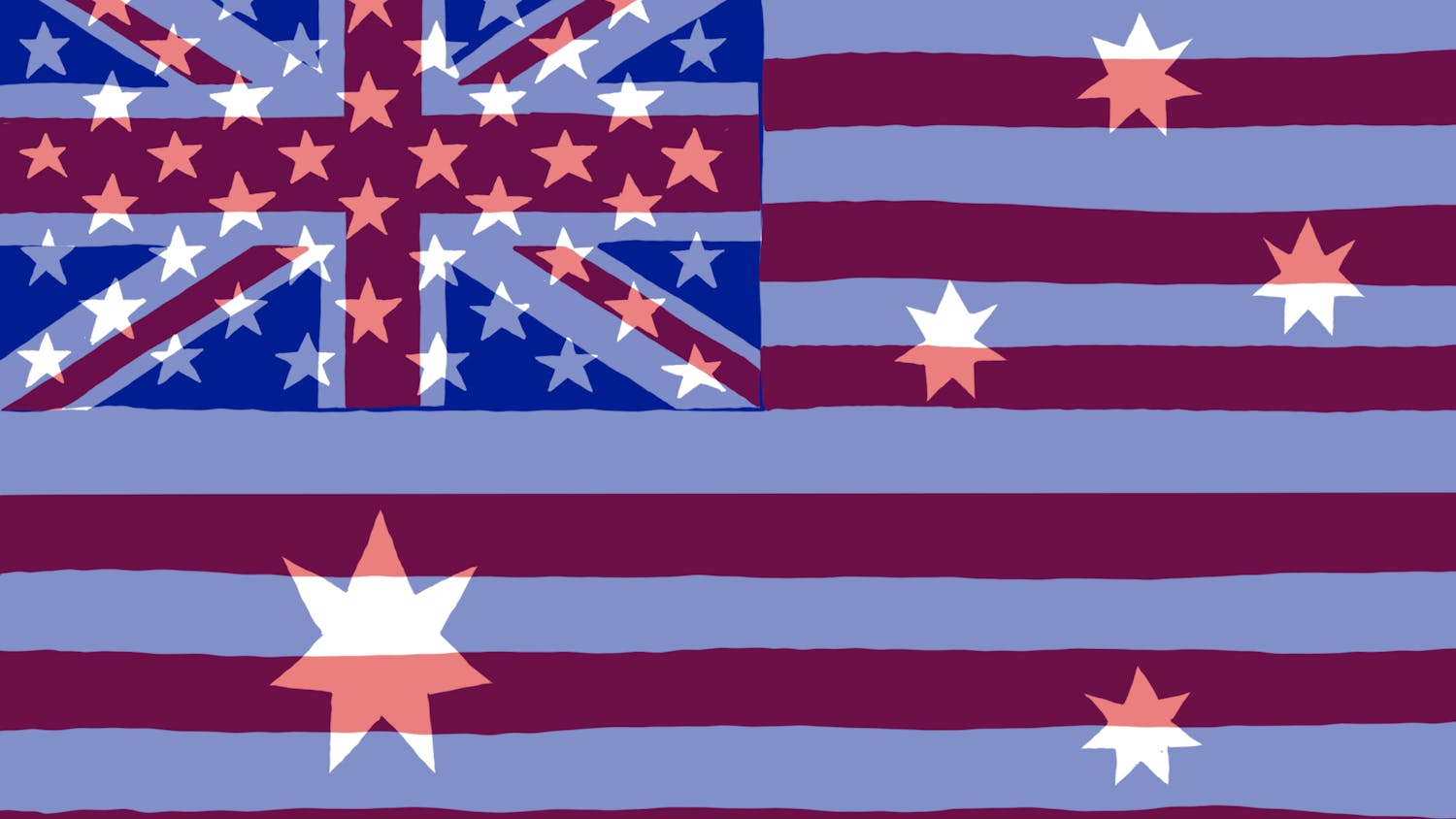

Of course, Dartmouth has cycled through many generations of slang over the school’s 250 years of history. I did some digging in the College archives at Rauner Special Collections Library, and I unearthed a book called “A Collection of College Words and Customs” by B. H. Hall, written in 1856. Hall compiled a dictionary of lingo used at colleges in America and Britain in the 1850s, including several Dartmouth-specific words. Here a few of my favorites:

1. BULL. To “make a poor recitation.” Modern translation: to “bomb” a test.

2. FISHING. Trying to “gain the good-will of the Faculty by any special means.” Modern translation: “teacher’s pet.”

3. GUARDING. A custom in which “persons masked would go into another’s room at night, and oblige him to do anything they commanded him, as to get under his bed, sit with his feet in a pail of water,” etc. Modern equivalent: hazing.

4. GUM. “A trick; a deception.” Modern translation: to make a fool of someone.

Across American colleges in general, 1850s slang looked very different from the words we use now. Students said “chum” for “roommate” and “cramming” instead of “studying.” “Muff” meant “a foolish fellow,” and an intoxicated person was “blown.” Practically none of that slang survives now, at least not in its original form. You could say college students of that generation spoke an entirely different slang dialect from what we speak today.

Given the recent shifts in student lingo and the vast changes that have occurred in the past century and a half, it is only a matter of time before current Dartmouth slang goes extinct. What the kids are saying today, they probably won’t be saying in 15 or 20 years. But as the editor writes in his introduction to Hall’s “College Words and Customs,” “there is nothing in language or manners too insignificant for the attention of those who are desirous of studying the diversified development of the character of man.” Slang defines and shapes our culture, and it makes Dartmouth students who we are, even if our vocabulary –— like our school culture –— is forever evolving.