Noises can be readily identified as pleasant or unpleasant. For me, the sound of raindrops on my window is pleasant, while the sound of nails scraping against a chalkboard is decidedly unpleasant. These evaluations are made possible by complex chemical pathways in my brain that convert sensory stimuli into nuanced physical and affective responses. But how do we respond to an absence of stimuli? What if there are no sound waves to press against our ear drums?

Researchers placed subjects alone in a sparsely furnished laboratory containing a button which, when pressed, delivered a painful electric shock. After feeling the test shock, all subjects said they would rather pay a fee than receive a second shock; however, within 15 minutes of solitary silence, 67 percent of men and 25 percent of women pressed the button in order to break the monotony. They were so desperate for a stimulus — any stimulus — that they were willing to suffer a shock they knew to be painful.

Shocks can be uncomfortable, but so can silence. When left alone, silence can create space for thoughts that are better left buried. In the absence of stimulation, nagging anxieties and suppressed doubts — unearthed through self-reflection invoked by activity in what neuroscientists call the “default mode network” — rise to the surface of our conscious mind. In American culture, this effect is seemingly amplified in the presence of a new acquaintance.

Brandon Nye ’20, a self-described introvert, is content to spend time alone in his room.

“I actually spend most of my day in silence,” he said.

But for Nye, silence in the context of a conversation has an entirely different effect. A lull can mean you’re not being engaging enough, or you’re not interesting enough to draw out conversation. It is the implications of silence rather than silence itself that Nye finds unpleasant. Silence is the result of having nothing to say, and, in American culture, to have nothing to say is to be uninteresting, odd, a bore.

Sociological research shows that Americans actively avoid silence, labeling even a four-second lull in conversation as “awkward.” To stave off discomfort, we validate our conversational partners’ stories with a near-constant stream of “yeahs,” “yeps” and side comments, and we pad our speech with empty fillers like “um,” “uh” and “you know” instead of pausing for a breath.

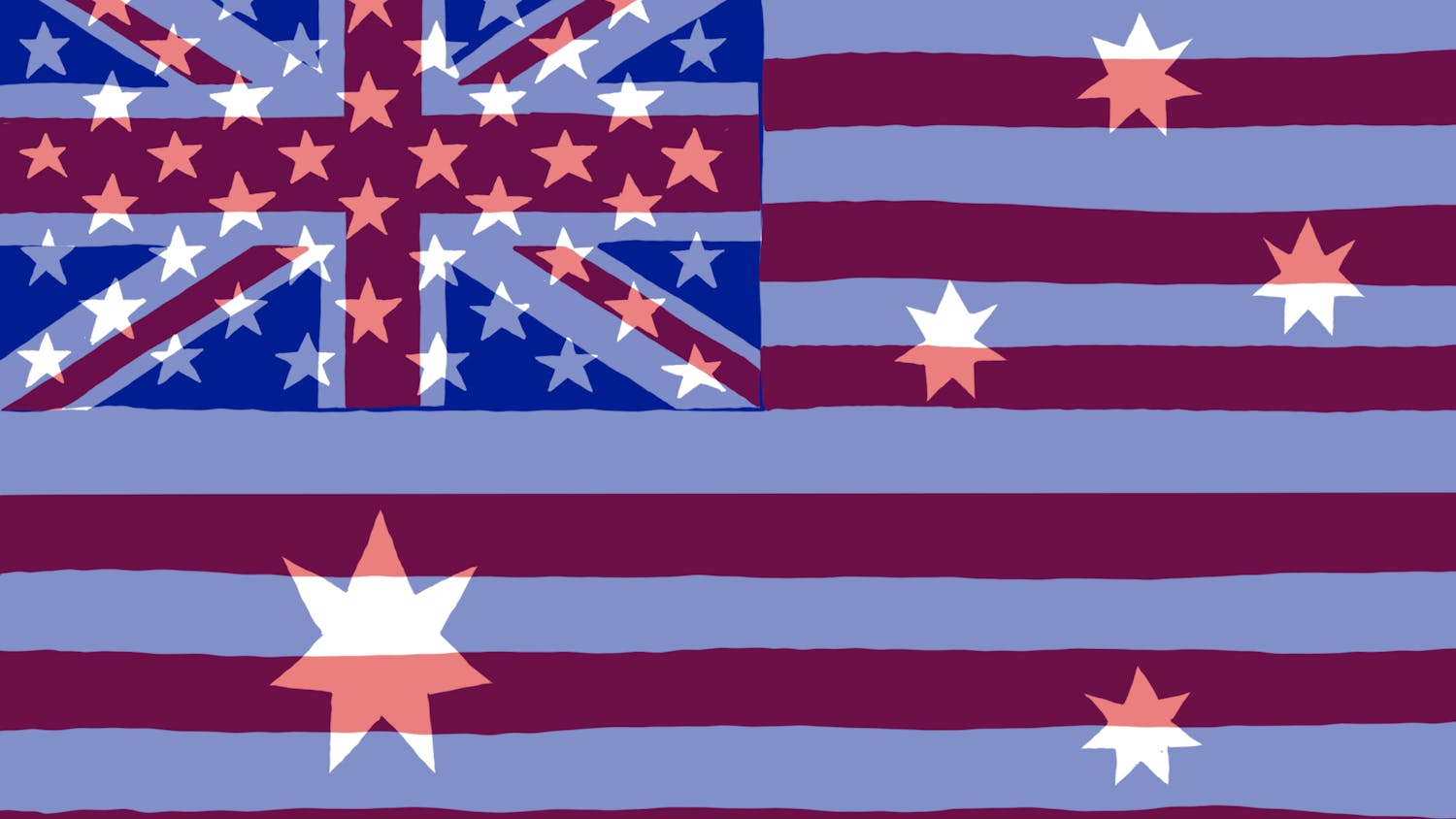

While not unique to America, this stigmatization of silence is certainly not universal. In Japan, eight-second silences during business meetings are acceptable, even typical. The Finnish, Norwegians and Swedes fall silent in the midst of conversations in order to process what they are hearing and respond appropriately. These discrepancies exist partially because Americans are unique in their belief that communication is largely verbal — other cultures recognize silence as a means of communication. Silence can index respect or judgment or displeasure.

Alex Waterhouse ’20 grew up in England and has noticed the American avoidance of silence since coming to Dartmouth.

“I feel like silence doesn’t happen very often here in comparison to the U.K.,” he said. “In a group of Americans, I feel like someone would jump into a silence much quicker, just to say something or carry on a previous thought, whereas if there’s nothing more to be said in the U.K., people just won’t say anything for a little bit until something else comes up.”

According to Waterhouse, Brits are perfectly comfortable with having nothing to say. He described these natural lulls in conversation as “contented silences” in which “you just stop talking and think about it for a minute.”

While silences prompted Waterhouse to reflect on the topic, silences prompted Sara Hileman ’20 to reflect on her role in the conversation. Hileman described silences as anything but contented, particularly if she is with someone she doesn’t know well.

“If I’m nervous about what the other person is thinking of the conversation, then I’ll probably panic a little internally,” she said.

She tends to respond to awkward silences by filling them by any means possible.

“I’ll just kind of start babbling about myself and end up sharing some detail that probably no one cares about,” she said.

This compulsion might come from a perceived need to “prove” herself, Hileman said.

Waterhouse acknowledged that pressures to continue conversation exist in certain situations.

“If you’re in a situation where you are expected to keep up conversation, then if you don’t do that, it would be awkward,” he said.

But for Hileman and Nye, simply conforming to expectations is not enough to make a silence comfortable. They see silence as a sign of intimacy; it requires a certain degree of understanding and trust. To share silence with another person is to be “comfortable just with each other’s presence,” Hileman explained.

A shared silence means there is no pressure to impress, no anxiety-ridden speculation as to the thoughts of the other person. More importantly, it indicates an acceptance, and even enjoyment, of that which two-thirds of men and one quarter of women in America were not willing to endure alone.

Author Virginia Woolf, famous for using stream-of-consciousness writing in monologues, would spend hours in silence, trying to activate her default mode network and understand the workings of her own mind. This intentionality was necessary because most of our musings happen below conscious awareness. And most of us, unlike Woolf, would rather keep it this way — excessive activity in the default mode network is associated with mood disorders like depression. It seems that we are only comfortable diving into the private depths of our mind in the presence of someone we trust.