“Oct. 18, 2016: Worked in the warehouse all morning, sorting winter jackets and shoes. Ate lunch with some new volunteers from Dover who are here for the week. We went into the camp this afternoon to distribute shoes — it was super cold and chaotic as everyone wants shoes before the demolition of the camp. There is sadly no way to give everyone everything they need. We are trying to distribute as much as possible before the demolition so we didn’t leave the camp till sundown (6:30 p.m.). Another tiring day but again surprised by how Care4Calais has formed relationships and trust within the Jungle.”

This is a short journal entry of mine from exactly one year ago today when I was volunteering in Calais, France in the large refugee settlement known as the “Jungle.”

The Calais Refugee Settlement was Europe’s largest unofficial refugee settlement in the port city of Calais. Calais sits on the English Channel and is approximately 20 miles from England, making it an important linkage point between France and England. The Jungle, a degrading and racialized nickname given to the settlement, is sprawled next to an interstate that leads to the Calais Port. This settlement of roughly 7,000 refugees, primarily male and Afghan, Sudanese and Eritrean, was not maintained or recognized by the United Nations High Commissions on Refugees, as most refugee camps are. This means that its residents relied on local NGOs for essentials such as food, clothing, legal aid, medical assistance and other critical supplies.

The living conditions in this camp, mostly comprised of small tents, were exceptionally bad as there was no infrastructure, and it was sprawled across sandy dunes, which meant that any rain caused serious flooding — and it rains a lot in Northern France! Most refugees dreamed of claiming asylum in England because they spoke English, had family already in England and believed there was a strong job market. On Oct. 24, 2016, the French government ordered the eviction of the refugee camp as it came to symbolize Europe’s, particularly France’s, failure to respond responsibly to the exploding refugee crisis in 2015. The government established “Welcome Centers” throughout France to house refugees for a short amount of time after the eviction before being forced to decide to claim French asylum or find other legal paths to staying in Europe. Instead, many refugees chose to leave the centers and remain unauthorized in France in hopes of still making it to the U.K. While this eviction successfully removed the physical presence of the Jungle, refugees are still arriving in large numbers to Calais as it is the closest access point to England from France. As there is no large camp for arriving refugees to join, many are living on the streets or squatting in small, squalid camps throughout Northern France.

One may be wondering how I found myself volunteering in the Jungle and what it was like. I discovered this opportunity from an NPR piece about a British woman’s experience volunteering for Care4Calais, the NGO I would eventually volunteer with. As a geography major and French minor, I was intrigued to pursue this experience as it bridged two realms of personal and academic interest.

I am not able to adequately summarize what I did while volunteering in this short piece as it changed day to day and became much more complicated once the evictions started on Oct. 24. I will instead focus on two tenets of providing aid to the refugees that stuck with me and shaped my experience. These values are both grounded in the value of humanization in a setting that seeks to dehumanize. The Jungle was not a comfortable place to live. From squalid living conditions, to the complicated politics and social dynamics amongst the camp residents, to the liminal state in which the camp and its residents occupied, to the histories each refugee carried with them — it was a dehumanizing place. Recognizing this, Care4Calais aimed to provide “dignified aid.” In practice, this was exemplified through what type of aid was delivered and its delivery method. Shoes, winter jackets, warm fleeces and pants were the staple clothing items that were distributed to refugees daily throughout the camp. The clothing came from donations given to Care4Calais from countless sources in England and France. As volunteers, it was our job to sort the clothing and prepare it for distribution. This meant sorting through every item of clothing and asking ourselves, “Would I wear this?” and “How would I feel if I was gifted this?” If the answer was “yes” to wearing it and excited about receiving it, we would keep it for the Jungle refugees. Coupled with this methodology of choosing the highest quality goods to distribute, Care4Calais also had several distribution systems that attempted to destigmatize one’s experience of receiving aid. For example, Care4Calais had a ticketing system to assure that no refugee needed to wait in long lines and guaranteed that everyone was given an equal chance to receive critical items. Of course, these systems were not bulletproof and were regularly abused, but it struck me how large scale emergency aid does have the potential to be dignified and contextual.

Another consequential moment during my experience in Calais that speaks to the importance and challenge of providing emergency aid in raw settings such as the Jungle was on Oct. 24 when François Hollande, the French president, issued the official statement for the eviction and demolition of the refugee settlement. This totally rocked Care4Calais’ systems, but, more importantly, turned the lives of the refugees upside down in a matter of seconds. As decrepit as the Jungle was, many refugees who I became familiar with told me how important the tent city was to them because of the communities and friendships they formed. Eventually everyone wanted to arrive in England, but in the meantime, the Jungle became a place of relative familiarity, certainty and comfort. With the eviction, that all changed. Communities were torn apart, refugees suddenly became much more vulnerable as the threat of deportation was exponentially higher and the dream of making it to England suddenly seemed out of grasp. Care4Calais decided to shift protocol from daily distributions of material goods to the distribution of information.

During the eviction, Care4Calais had several teams throughout the camp spreading basic information about the eviction. Our job was not to advise but instead to inform the residents of their options and what to expect in the coming days if they stayed in the Jungle or if they followed the directions and were resettled in welcome centers throughout France. As volunteers want the best for the refugees, we believed arming them with information was the best way to assure they could prepare for the upcoming changes. Given my position, it made me uncomfortable to urge refugees to leave the Jungle, a place they considered a type of home, for an unknown place that may put them in more danger or hinder their ability to develop important friendships and communities. I never grew comfortable with such dynamics while in Calais, and still have not today, but it was the best we could do given the circumstances.

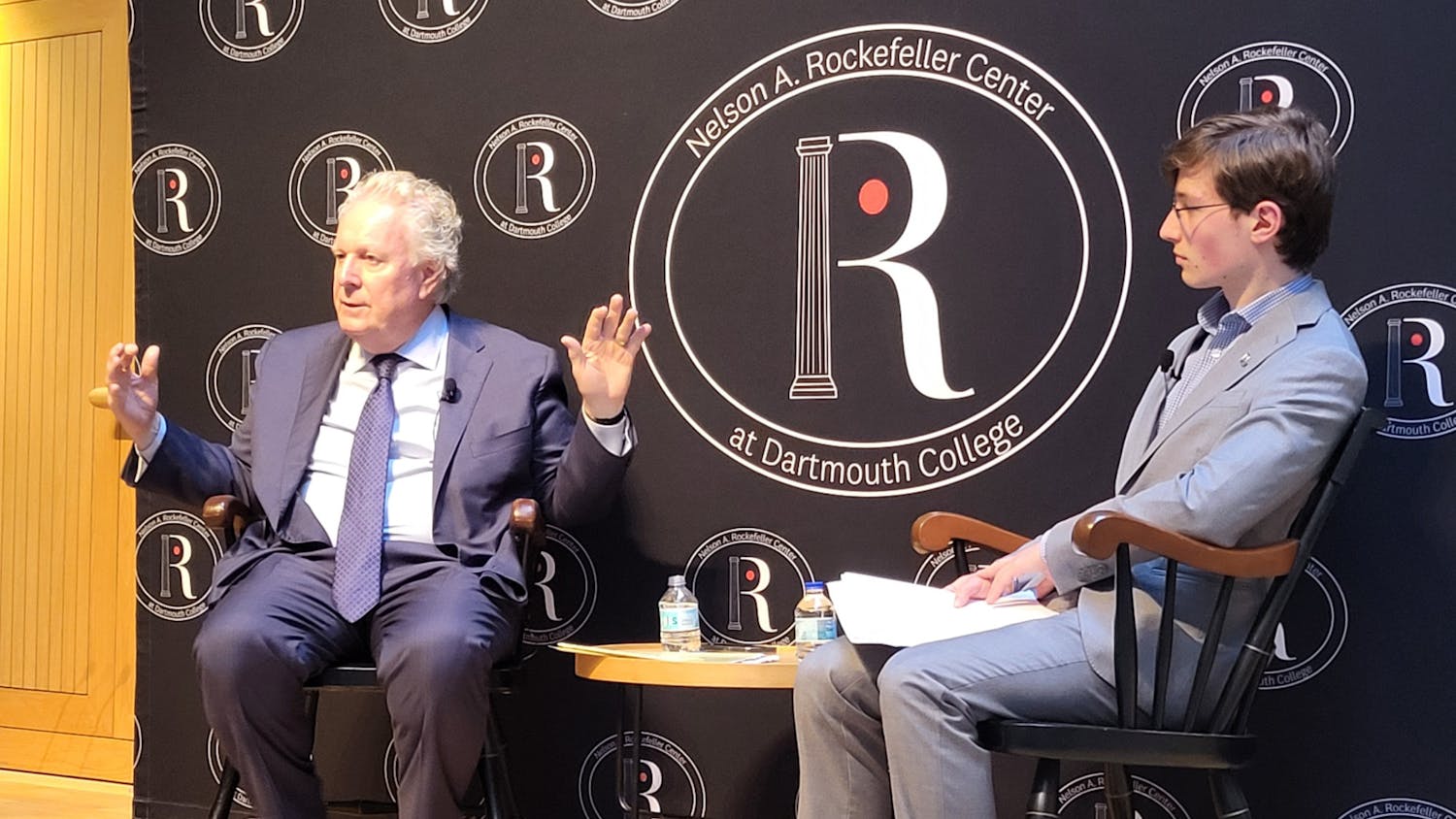

Oct. 18, 2017: While a day at Dartmouth is far removed from the realities of Calais, I often think about that dreary port city and the people I met there. I think about the many chai teas I shared alongside volunteers and refugees, about the endless mountain of donations, about the stories I heard, but mostly about my privilege in being able to leave Calais after a month and cross international borders without a worry. Since returning from Calais and reflecting past the “crazy, once in a lifetime” experiences, I’ve begun to think much more critically about my time as a volunteer for a large NGO. I’ve attempted to engage with the moral questions of humanitarian aid, especially the challenges pertaining to humanitarian aid workers and volunteers, and to better understand the discourse that surrounds refugees and immigrants today. From a personal standpoint, my time in Calais forced me to grow in tremendous ways. It is not worth listing all my many personal lessons, other than the importance of humility and self-reflexivity.