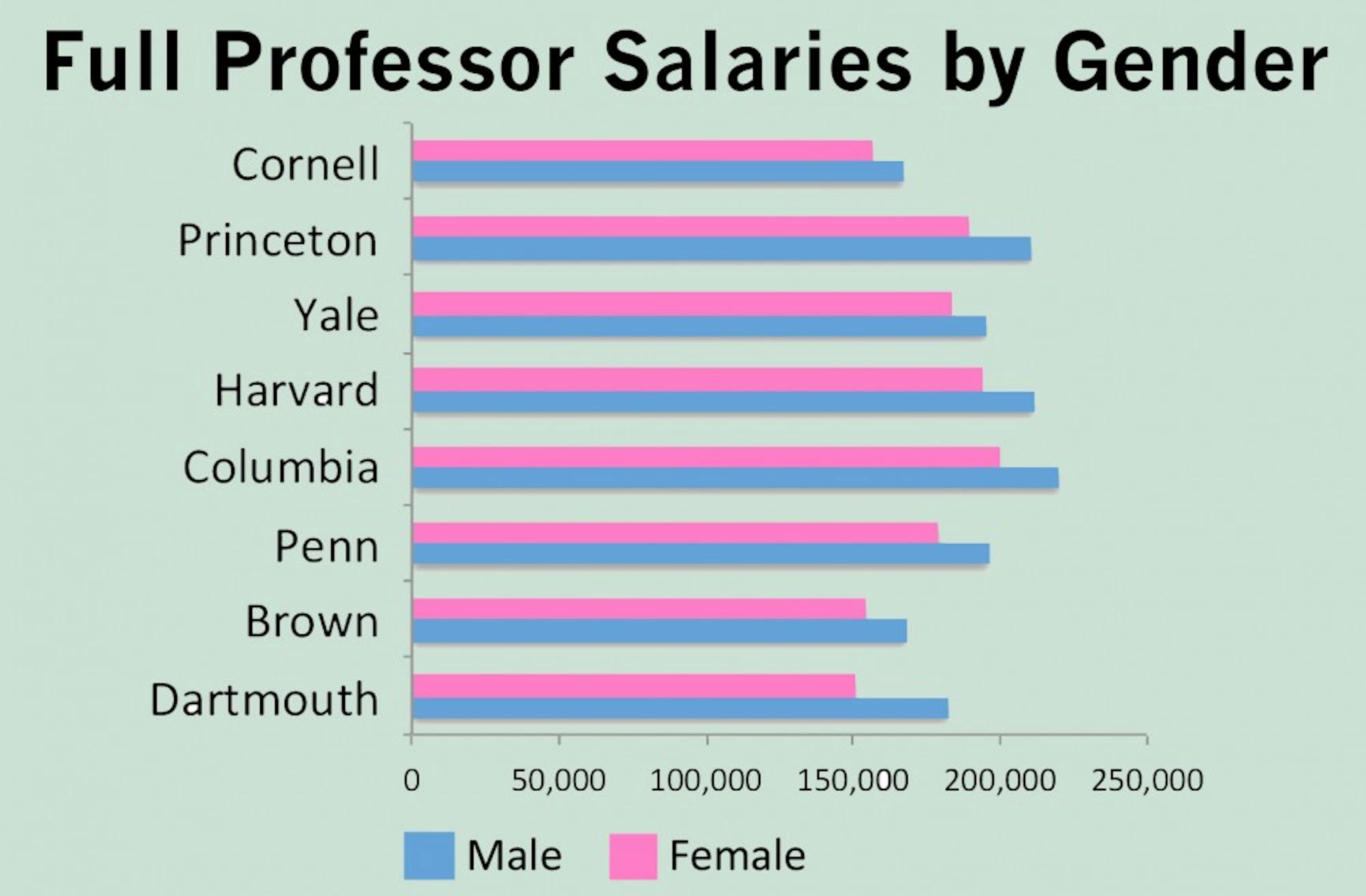

Female full professors at Dartmouth make, on average, 82.8 percent of what their male colleagues earn, giving Dartmouth the largest gap in annual wages for full professors in the Ivy League. On average, male tenured professors at the College make $182,500 while their female counterparts make $151,100, according to the 2013-14 American Association of University Professors Faculty Salary Survey published last week by the Chronicle of Higher Education.

This statistic shoes a wider gap than in 2012-2013, when female full professors were paid 83.2 percent of what their male colleagues earned.

Among the Ivies, Yale University boasts the lowest wage gap, with female full professors making 93.8 percent of what male full professors make. Cornell University and Brown University follow Yale, with female professors bringing in 93.7 and 91.9 percent of male professors’s salaries, respectively. Princeton University follows Dartmouth in greatest wage difference by gender among full professors, with women earning 89.9 percent of their male colleagues’ salaries.

Full professors tend to be older than associate and assistant professors, visiting assistant sociology professor Kristin Smith said, adding that the wage discrimination that existed in the 1960s and 1970s may persist today. Faculty who receive a promotion to full professor are further along in their careers, explaining the lower disparity among male and female associate professors, who tend to be younger.

Dartmouth conducts an externally commissioned survey every few years to determine if there are any systematic biases in the wage process, dean of the faculty of arts and sciences Michael Mastanduno said. The school has conducted three surveys in the past decade, the most recent one occurring last year. Last year’s results showed no systematic biases in the wage process, he said.

In comparing the College to other Ivy League institutions, Mastanduno said that Dartmouth’s particular mix of professional schools contributes to it having the largest wage gap. Because the College is smaller, the school only has a few hundred full professors. Therefore, if two or three full female professors leave, it skews the numbers more dramatically than at other institutions.

Smith said she believes that because the wage gap numbers are public, some prospective faculty members may question whether the College would be a good fit. If candidates receive offers from Dartmouth, Harvard University, Princeton and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, they may view the other schools as a more welcoming place for female professors, she said.

“Personally,” she said, “I think it’s a reason to take pause and look at these numbers more carefully.”

The gender wage gap, however, narrows for newer professors. Female assistant professors make about 95 percent of what their male counterparts earn, the survey found. This gap is narrower than the College’s peer institutions.

Sociology professor Janice McCabe pointed to the possibility that wage gaps reflect salary differentiation at the time of hiring. Because salaries are largely determined by percentage increase each year, whether in the form of a bonus or cost-of-living wage, inequalities that exist when professors are hired only increase over time, she said.

In academia, Smith said, women and men tend to pursue different disciplines, for which wages differ.

Sociologists tend to be women while economists tend to be men, Smith said. Looking at salary compensation for sociology professors versus economics professors, economists across the board make more, Smith said.

McCabe said the process of salary negotiation differentiates the wages men and women receive in the general labor force. Women are less likely to negotiate, and when they do, she said, they are judged more harshly. Because it goes against gender stereotypes, women are seen as aggressive when negotiating, whereas men are viewed as assertive.

Determining salaries varies by individual, Mastanduno said, so the range of salaries among full professors is relatively large.

Important variables for determining pay include age, field of study and productivity, which includes teaching effectiveness and research work, Mastanduno said. For example, computer science and economics will typically pay more than Spanish literature.

Furthermore, departments with higher salaries, like the economics and computer science departments, tend to have more men than women, Mastanduno said, adding that Dartmouth employs more male professors, and they tend to stay in rank longer than female faculty.

Mastanduno also pointed out that the data from the Chronicle of Higher Education includes Dartmouth’s professional schools, where faculty tend to have higher salaries than professors in the arts and sciences.

“If we have a business school where salaries are a lot higher, and there tend to be a lot more men, that’s going to skew the data,” Mastanduno said.

About 41 percent of College of Arts and Sciences faculty are women, the number dropping to 36 percent among tenured faculty.

At the Tuck School of Business, about 25 percent of faculty are female, and 12 percent of tenured faculty are. At the Thayer School of Engineering, around 18 percent of faculty are women, dropping to about 10 percent for women. At the Geisel School of Medicine, women comprise about 41 percent of faculty members, and 17 percent of tenured faculty, according to the College fact book.